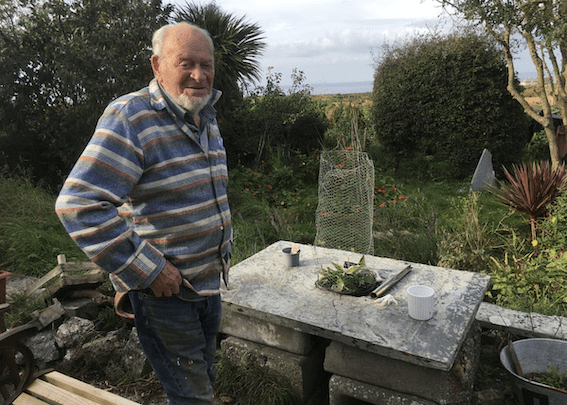

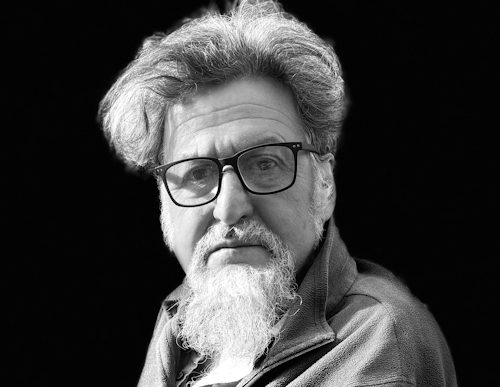

Part two of an extensive interview with performance artist and painter Ken Turner talking to former Action Space member and curator/writer Rob La Frenais, who joined the group in the early ’70s before going on to edit the ground-breaking Performance Magazine in the ’80s. [Read Part I of this interview here.]

La Frenais spoke to Ken in the garden of his studio at St Ives about his trenchant views on philosophy, politics, performance and painting, and why he keeps performing and protesting.

****

…I’m trying to bring us up to the moment of the founding of Action Space.

The founding was actually at Joan Littlewood’s Blow Up City. Because I said to myself, I mean, when it was erected there and happening, it had music, people going through it, looking at it, those photographs and saying, what is this? Poking at it, touching the artwork. I thought, this is amazing. This is quite a revelation. I’ve constructed something where people are just going through it. Now it’s called immersive art. So that people were just in it and looking at it, touching it and sitting in it. That’s what showed me the possibilities.

That was the beginning. That was the real spark after all this buildup of searching in my mind, experimenting, working outside in the streets with the Barnet students, all that. It was in the City of London festival. Next to All Hallows Church. It was a big paved area. And the People Show came, and they did a performance coming and driving a car into this area with John Darling standing on the roof of the van, shouting to everybody. I don’t know what he said, but it was so exciting. I thought, wow, I could do that! It was a dynamic moment.

I remember a similar moment seeing Welfare State in the shadow of Coventry Cathedral. Around about 1970.

Yes, Welfare State was interesting. But, you know, Welfare State was interested in entertainment, primarily. Because they had a band and the band actually led the whole movement of their movement and structures and ideas.Processions were made to gather an audience. That was their main reason for doing that. And they put up a tent or their structure. I called a tent, but it was more than a tent. It was going towards something extraordinary in a building. But it was primarily there for an audience to be entertained and not in participation.

I’d be interested to know what John Fox and Sue Gill would say about that.

I had lots of arguments with John Fox. Really nice guy. And we had lots of talks about it. So I thought, well, having a band is quite important in the way for him. And Action Space doesn’t have a band. So we started gathering a band finally.

So there was a communication of ideas there.

Yes it was all interweaving, picking up ideas and trying them out. But what was important in Action Space, finally, when we were then after the City of London Festival, we went to St Katherine’s docks. Well, we built inflatables in St Katharine’s. But we went to Wapping for two weeks over two summers.

When one joined Action Space, people were still talking about what happened in Wapping. It was like a part of the growing mythology.

So Wapping was really the birthplace. I mean, I said that City of London with Joan Littlewood was the birthplace. It was the birthplace of an idea. But Wapping was the birthplace of the practice. Practice then was experimental and gradual.

And Wapping was the first time you were working in a place where ordinary people lived.

We engaged with the people, but it was difficult to call it an art project, although we had painting, we had games, we had people like Jeff Nuttall, AMM coming in.

Did you then move to St Katherine’s and start building inflatables? I just want you to describe how that physical transition took place.

Well, St Katherine’s dock was interesting because of the space itself,and it gave studios to loads of artists. Graham Stevens was there as well. So we asked him if we could come into his studio and make some inflatables.

Oh, okay. So your conversation with Graham Stevens was part of this process?

He understood what we were doing, and he said, yes, you can use my studio or equipment or know. He was working on inflatables with electronics joining things. And we said, no, we’ll stick to glue, Bostic. And so one of the students from Barnet made the first big air house in that studio. And we blew it up in the grounds, in the basin itself, outside the building, It emerged with this first big warehouse, a 20-foot-square tube. We blew it up on vacuum cleaners. And we thought, wow, this is incredible! We can actually go from here to doing other structures. So that was me principally doing that. And the students. It was Richard Harper, one of the students. Actually, he got to make it because I was also working on the framing. And so he made it in the studios of Graham Stevens and blew it up there. And we were both excited by what we’d done.

It was this first realisation that you could make structure suddenly blow it up into the environment and change the whole environment. At the same time the Wapping thing was happening. But we didn’t use big inflatables there. We just used small ones, small cushions, as it were. And we were experimenting with drama, with music. Alan Nisbet came. Alan Nisbet was a composer. I said, ‘that’s interesting -you’re a composer. What kind of music do you do?’ He said ‘my kind of music wouldn’t interest you’. And I said, ‘well, is it kind of very advanced? Can I call it that? Or experimental?’ He said, yes, experimental. Then I lost contact with him, and when I was doing the Joan Littlewood thing, he walked into the structure and I said to him, ‘oh, Alan, can you spare a moment? I’ve got something wrong with my speakers’. So he said, ‘okay, I’ll have a look’. And he looked and he got the sound working again. I said,’ thanks very much. Would you like to join Action Space structure?’ He said, yes. Okay. On the spot!

Anyway, so let’s just go back to that moment. You’re in the air house and Alan walks in and immediately agrees to join what you’re doing. It’s the same as when I met Action Space and said ‘Can I join you?’ They said, ‘yes come to London. Come and see us at Harmood Street.’ So literally, within two days, I’d got on a train, and walked around to Action Space and said ‘I met you a few days ago, I want to join’. Literally.

Anybody could come in, yes. Well, part of that was the feeling that if people wanted to do something, they should do it. You shouldn’t stop them. So if you wanted to join or come in, we didn’t say, what can you do? We said, yes, come in and experience it and do what you can. Find out what you can do.

I think that’s part of the uniqueness. There were very few groups that actually had that approach, that anybody could walk in.

It was built on anarchy. It was also built on humanity, the idea of humanity. Everything was possible. And when I got a job at the Central School of Art, I was interviewed by the head of the department and we had lunch together and I told him about Action Space, which I’d just begun to do and I told him I was a painter. And he said, after having lunch and our conversations, he said, you’ve got the job. He never saw my work. And that’s because he was a Quaker. And Quakerism is very close to an anarchic principle. Anybody can enter and say things.

If you think about that, yes, everybody can speak in a Quaker meeting. You’re absolutely right.

If there’s anybody that said, I’d like to join your group or movement or whatever that meant they had some kind of desire. And that desire was very important to actually open up, that they had space to open up. iIt leads to education. That’s what you should say in education, in universities or early school, it actually happens in playgroups. And remember, Mary and I were working in playgroups. I read that here with our children and we could see the possibilities within people as young children, infants, what they could do and what they were allowed to do. So allowed to make a mess or do whatever they wanted to. And that was a principle of Action Space.

So could you talk about the thoughts you and Mary had about anarchy and how that worked in the way we were all recruited?

Yeah, I have a book called ABC of Anarchism (by Alexander Berkman). Written in 1929. Okay, it’s an interesting book in that you don’t lose control. You have control, but it’s another kind of control. The control is the strength of your ideas so if you have strong ideas and are compatible with that, you have an empathy, So your feelings are very important. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead spoke about feeling as a deep sense of intelligent emotion. It’s something that if you say, oh, I have feelings. What does that mean? Feelings of love, feelings of lust, feelings of desire, feelings of transcendental ideas, feelings. And those feelings are incredibly important.

As a painter, being a painter, I know about how to look and how to understand what you see and how to interpret what you see is incredibly important. And it’s about not only just physically seeing something, but also about feeling, about what you’re seeing. So the emotional experience is a valid experience. The emotional content, emotional feeling, the emotional condition in which you feel yourself, then that is the reality of your own personality, your own character, or. I don’t like to think of egos. I think of egos as something a bit evil. But your being is a much more important thing. That’s why I call myself a sense of being. That there is a life being Ken Turner. So the being is important and that’s a feeling of your other self or your otherness.

So how does that transform itself into a social organism like Action Space?

Well, it’s there as a base, which you don’t have to think about. It’s there. And I had it from early birth. Look, I hate to say it, but it’s about good leadership and it’s about good teaching. When I was teaching, from knowing my students later in life, they knew I had a certain power or a certain knowledge. It’s not power, it’s because knowledge is power. And that’s going back to the philosopher. Knowledge and power are very dangerous things to bring together. And that’s what happens if you don’t have that faith, which binds it into something true, into something real. It’s then projected into the environment, it’s projected into, if you’re having a meeting. If you’re a leader with compassion and feelings, you could project that feeling. And it’s a kind of authority, but it’s an authority that springs from deep down into the desire for aesthetic moral behaviour. That sense of governing is passed to other people.So you hand over that power and other people take it up.

Yes, we had that with Extinction Rebellion. Somebody says, ‘oh, why don’t we do an action like this?’ And they say, ‘you do it, you plan it, you get on with it’. There’s this philosophy saying, ‘you do it’.

Who did the opposite? Ed Berman (Director of Interaction) He had omnipotent power. Because of his ideas and speech, and because he did come from a drama background and he knew how to handle people and he pursued it to an endless sort of dominance.

That’s why he disliked Action Space so much.

Because we were open. He was that close like that, directing. All his drama was directing like that. Principles of, you can join in or go! But we said, come on in. Come in, please. We’re happy for you to be doing what you want to do. We had the power to set it so that it was that liberal, even though I hate the word liberal, but open is a better way This is why I called it a university. Finally, as opposed to the actual universities set up by the government or educational situations. I know from people like Amanda, who works in Manchester, has now retired, Jane in Brighton, and how my own school, the Central and St. Martin’s, I understand how they worked, and they were just oligarchies.

Yes, I never went to university, but Action Space was my university.

I mean, it turned out to be like that, but it wasn’t the initial ideas. It just grew. And it grew from the idea of sharing and sharing knowledge and experience and so on, in a practical sense. And so it gave people confidence to grow within it. And that’s all you can do. You say to people, grow, just use the ideas we’ve set, or seeds we’ve set, and see what you come up with.

There’s the historical fact that Joseph Beuys was sacked from Dusseldorf Academy for inviting anyone who wanted to come in from the city to his lectures.

When they came in from art school, music school, drama school, ballet school, that was in contrast to the control that those universities had. Which speaks for itself. You had to communicate it either through, first of all, through ideas and words, then by action and then they would get the confidence of the other people. So that’s what you had to do. And that’s why we had a firm bond, as it were. You had to bond with people through ideas and through action.

Then there was a slow transformation within Action Space physically to become an organisation even though it had these anarchic principles with people living in the short life housing, getting together every morning, eating together, having meetings and it became a more complex organism, if you like.

Well, I could answer that, because the build-up with Mary and myself was very important, that we were a bond together. We knew what we were aspiring to. Myself, really, as an artist, I knew that there was something there very important to do and it was backed up by my rejection of the art world. So that was so powerful, to actually step outside the art world into the street, playgrounds and gardens and so on, that was the excitement. And from my idea of doing that, it must have influenced the people.

If you have a spark or a germ of an idea and that idea has this humanity, a sense of humanity and humanity as a relationship. Being human is not enough. Just being human is material and you’re existing and that’s all. So you have to have this. And going back to my ideas of feeling and imagination and play, so if you have those working together, it influences people. So, from that little germ of an idea, which is very powerful, you transmit it unconsciously, sometimes, to the other people coming in. So the people didn’t come in in crowds and hordes of people, they came in individually or as couples. And that then was like feeding, feeding the original ideas. So there would be a correspondence between the new people coming in, and they would be added to the pot, as it were.

That growing sense of concepts, of how new ideas and arts could function, that was important. But you see, we didn’t have the Internet. Which is amazing because we were able to communicate with our actions just by physically being in a local situation, because we were involved with the local area, in Kentish Town. We used to go to the neighbourhood meetings. So we were part of that.

In those (pre-internet) days you’d only find out where to be by being in the right place at the right time or the wrong time, and talking to somebody.

As I said before about the Charing Cross basement of Better Books.They understood what was happening, and they let their basement out to artists doing things and the People Show was one of them. And I went there and was inspired. So it’s a matter of inspiring people with your actions. The actions speak louder than words.

I wonder if it could ever be replaced in the virtual.

No, because, only if there’s a revolution. Because I have a dismay of what’s going on globally. And I think that the internet is so powerful and it’s actually based on knowledge, and knowledge is power, and that’s how they look at it. That’s what happens. Politicians talk about misinformation, but it’s not misinformation, it’s information of power. And people are grabbing the power wherever they can and using it.

Just look at Trump. He’s just using the power of the Internet and that’s what works. He gets to people. So that’s what you have to do if you want to change the world or make the world a so-called better place. And politicians are saying all the time, we’ll make the world a better place. The Labour party says the same thing. The Conservative party says the same thing. They’re all saying the same thing. They’re up the wrong path. They’re using outdated language, ways of using language, which is like imperialistic language. Trump does that all the time. This is where I come back to aesthetics, because very rarely do I find a politician who thinks about the aesthetic of politics. Jacques Ranciere talked about it a lot. So it’s like a politicisation of aesthetics, or is it an aestheticisation of politics? Which way round is it? And I think that’s important. So I see aesthetics being a moral code, and you do the right thing because you have that moral code.

We had to connect to local politicians, we had to present ourselves to the Arts Council. We had, to some extent, some pressure on us to deliver.

We didn’t have to pressure it. It happened automatically. I was invited on to a Council meeting, a Council conference. And I was given the lead in one of the, what do they call, they take the whole conference and then they had several leaders who did breakouts or whatever. I had one of those, and I was sitting right, I was the leader, and I had all these councillors around me, and I had to lead it, and I was inexperienced, so I couldn’t do it properly. They were very scathing of how I led it. And I failed in that. I absolutely failed. I wouldn’t fail now, because I know what to do. But that is the sense of I didn’t have the power in that situation, which wasn’t like a conventional institutional power, wasn’t real power. It was an institutionalised power, and it wasn’t aestheticised. So I failed.

But it was interesting that they asked me, because I was an unseen pressure of what my actions were. So the Arts Council were looking at us and thinking, oh, they’re doing something quite interesting and different. So because of that different thing, which is going back to Derrida, really the difference is important. So thinking differently was something that got us into, like the Arts Council would be asking us. We were influencing the Arts Council, but in the wrong way. They were taking it the wrong way and calling it community art when it wasn’t community art. We were artists who were trying to find alternatives to the art world simply as that. And that was very powerful. But it could be misunderstood, which is how the Arts Council looked at it. And they made this awful mistake of pursuing community art and making art workers instead of artists. So if you’re an art worker, you don’t have ideas of changing society, you just have ideas of ministering to a sick society.

Yes, this hybrid of community arts was an unwelcome hybrid, in my view. It was kind of politically convenient for certain people.

Joseph Beuys said everybody is an artist. And even my son questioned me on that and said, if everybody’s an artist, why are you working? Everybody’s an artist. They can appreciate art. Which is a complete misunderstanding of what Beuys meant.

He actually said, every human being has the potential and capability to become an artist.

What he said after that was everybody is born unequal with talent. That’s right. And it wouldn’t work.

He also went on to say another thing that I thought was important was not only that everyone has the potential to become an artist, but every human activity has the potential to become art.

It needs a hell of a lot of schooling and education to change ideas or to implant ideas, and because they’re prejudiced because of their education. And the education system is so bad that it leaves out the idea of aesthetics completely. It doesn’t understand what phenomenology is about. It doesn’t understand philosophies of looking and seeing and understanding and feeling and so on. So you’re against a steel wall of resistance, automatic resistance, in trying to implant ideas. And that’s why Action Space found it so difficult to do that. And they could only do it through the penetration of imagination through art, like Herbert Read’s book, ‘Education Through Art’. Because Action Space only went so far. It didn’t go far enough. And I said there was so much action, there were not enough ideas, not enough thought. Action over thought. So you had to bring the two together and it never brought them together.

So what should have happened in Action Space was that you had sessions where you discussed ideas and philosophies and we rarely did that. Because the action took over. The action was very physical and the physicality took over from the mentality. I often think about that and was sad about it because it’s something that I didn’t have the capacity in my intelligence to think about it that much. But after Action Space, I thought about it. And the way that I was dealing with it was to concentrate on performance. And that’s why when I left Action Space, I did loads of performances.

People wanted us, places booked us. It did too much action. We had teams going out in vans and ambulances and taking part in events. We did discuss what we were going to do beforehand, but it was, in the end, as if we were on a bit of a treadmill of action, this kind of rolling action made it difficult to ‘stop moment’, as Goethe says, to go into the contemplative and to think a bit about what we’re doing.

It should have been my job and Mary’s job, to actually bring us into that state, which is totally different to the action state. So it would not be Action Space, but idea space and philosophical space. I didn’t have the knowledge, but since then I’ve got the knowledge through reading philosophies, and I can understand more about what should have happened. And that, as you say, it should have been more contemplative, sort of summing up what that action after the action, we should have come into discussion about summing up its purposes, its evaluation.

Yes we should have made space for that. We were too exhausted, one of the reasons.

But we should have done it. We should have allowed the space to happen. And we had that space in Harmood Street and the Drill Hall. We had that space to go into a room and say, okay, let’s now try and understand and analyse actually more deeply how we can further this action with ideas, rather than just action, action, action. So it should be ideas, action, ideas, action. Turning it over and over like that. And that would have made a huge difference if it became a real university. That’s what would have happened. But not, hopefully, to a university where you have critical thinking. So it wasn’t critical thinking we wanted to go into, which I’ve now realised it’s a whole absurd fantasy. Critical thinking is absurd and based on snatches of philosophy and not deep thoughts about what should be ideas.

So an ideal thing. I mean, in this kind of parallel universe model of Action Space could have been that we were more like a free university where we also had to go out into the world and do these events. But we also had to analyse them and maybe write about them.

We didn’t realise that we crashed Action Space completely. So we crashed it and destroyed it because it rested on both of us actually pursuing ideas and developing them. And it would have developed because I was starting to read Heidegger when I left Action Space, I started reading Heidegger. And if I’d been allowed to do that within Action Space, it would have changed.

Then there was a kind of implosion followed by an explosion in 1979.

It’s like crashing. I think it was a crash. The egg opening and scattering it, and ideas were flying all over the place and there’s no control anywhere. No belief anywhere. It’s gone. It was interesting, as you say, an implosion. That actually sums it up really well because you can’t bring it back again. You get something that’s just eking it out and exploding it outside. So, in retrospect, you see, when we’re talking about it now, because I’m older and because I have more experience in understanding things through my painting and through reading, I can do this quite easily. As I said, I can answer every point and say, no, that’s not what happened. No, this is what happened. This is how it went.

We didn’t give ourselves enough time to think about what we were doing and why we were doing it. I think that’s the fundamental thing.

I think we understood it innately, but we didn’t speak about it, we didn’t pursue it. And that was the failure, really. That’s why I talk of failure. And it was on the basis of philosophical ideas. It had to be, because I can’t think of painting without thinking about philosophy. And I think painting is philosophy itself. It is about philosophy of life. Action Space was about a philosophy of life. It wasn’t just a drama school or environmental school or anything like that, really. That was only incidental. That’s what the mechanics were. But the basis, the deep seated ideas, faith in something was through philosophical ideas. And I was only just beginning to think about that in that way. And that was my failure, which became the failure of Action Space.

I don’t think we can call it a total failure. I think what we can call it is an attempt to change history that didn’t fully succeed, but which did set off ripples that have had effects.

The Russian revolution is the same thing. 1917 in Russia, the black square was either a symbol for revolution or a retreat from aesthetics. And it was, in Malevich’s words, it was a retreat. It said, don’t change, don’t change, don’t revolutionise yourself. This is important. It’s the art that counts, not the revolution. And the rest of them went into propaganda constructionists, which weren’t leading anywhere, and people wouldn’t understand it anyway. The only good thing they did was to paint a train and push it through Soviet Russia, proclaiming that this was the new ideas of living. And when Stalin came in, he know, the people don’t like this bloody art. It’s all abstract and nonsense.

Well, it’s tragic. We’re seeing all that again after this massive explosion of contemporary art in Moscow and it’s just completely been destroyed and replaced by Putin’s propaganda.

John Berger was trying to go into Russia and find artists working now. I knew Berger, as you know, we were friends. And I think Berger was up the wrong street. He just missed it altogether because he didn’t have a real philosophy. He had a political idea, which wasn’t a real philosophy. I mean, you can’t have politics without a deep-seated philosophical idea about what humanity should be concerned with. And that’s what Action Space was. But we didn’t understand the philosophy. We were making it.

****

[Read Part I of this interview here.]

Rob La Frenais is an independent curator, artist, writer and lecturer and works closely with artists on original commissions. He founded Performance Magazine in 1979 and became an independent curator specialising in performance and installation in 1987 and continues to work and write internationally.