[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]ate Britain’s summer opening Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation is one of paradoxes, both in terms of content and the feelings that it elicits.

Known for his sharp and witty documentaries and unashamed championing of unfashionable elitist art; one could question whether a show that begins and ends with a castle and drags the visitor through rooms of his eclectic and entirely individualist collection, doesn’t do some injustice to his relevance to our times and simply compounds the notion of a rich kid indulging aesthetically precocious whims.

To do so, however, would be to succumb to a rather age specific egocentricity ourselves and to be blinkeredly insistent that all culture should necessarily be absolutely relevant to our own times. The rise and fall of Clark’s star is symptomatic of fads within art historical reputation, based upon fashion rather than intellectual rigour.

True, Clark’s attire and fusty enunciation might exemplify the mothy wardrobes and lexicon of an out of touch, decaying upper class, but he was radical in the sense that he wasn’t afraid to start arguments and to champion the serious with a twinkle in his eye. In that twinkle, one is aware that, behind the carefully enunciated words, is a man whose whole existence revolves around art, and that each phrase is born of a lifetime’s experience and understanding.

Tate’s attempt to resuscitate Clark’s reputation therefore, commendably takes a biographical approach, thematically arranged to reflect Clark’s life and work– his privileged upbringing, education at Oxford where he was influenced by the likes of Roger Fry, his position as Director of the National Gallery, his patronage, campaigning and broadcasting. The emphasis however, is very much upon his role as a collector who refused to embrace the ‘exhaustion’ of modernism.

It was some of his diabolical choices in this arena that has meant that Clark has had scant influence on long-term art making. What at first seems perplexing is that Tate makes no attempts to deny these catastrophes. His passion for copies yield horrors such as Duncan Grant’s ‘After Zurbarán’ and his vast array of Bloomsbury acquisitions looks positively kitsch. One is forced to either despair of, or admire him for his patronage of such evidently second rate painters in comparison to his Moores and Cezannes.

Clarke detested the increasing appreciation of European avant-garde movements like Surrealism, and he publicly denounced abstract art. Consequently the only the only abstraction in the show is a very conservative Ben Nicholson. It is unsurprising that such prejudices would ultimately undermine his credibility as an important twentieth century patron.

This may be a point of contention to many visitors who lament the absence of Bacon alongside the lonely Lucien Freud, but the purpose of the exhibition does not seem to hold a bastion for Clark as an arbiter of taste but to rather reveal the art that was pivotal in the formation of the unwavering conviction, lucidity and erudition that did actually build his formidable career.

Evident throughout are the little quirks, choices and indulgences that drove his almost childlike eagerness to immerse himself and others in Cezanne’s ‘sensation forte devant la nature’.

Highlights of this sensitivity and genuine excitement to embrace all aspects of culture include a collection of Catton’s designs for pub signs which, jauntily displayed next to an extract from a book of Renaissance choral music, are accompanied by a note of Clark’s enthusiastic testimony that he has acquired a ‘marvellous monument of English art’.

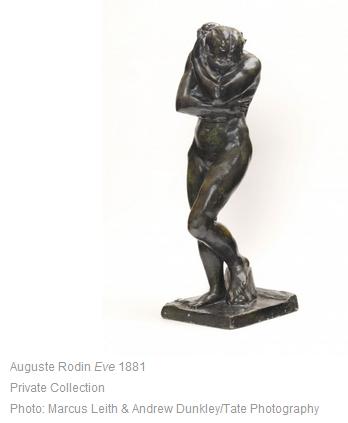

These touching idiosyncrasies are heightened by the fact that the exhibition replicates the manner of Clark’s own domestic display of his collections, largely amassed during the 1930s. Hence, here too it is ‘natural that a Hadriatic relief should come to rest under a Degas drawing’. Decorative arts such as French Ivory and Coptic textiles hold their own against a Rodin nude and design for a Stravinsky ballet.

This is, as the exhibition title would suggest, not just culture but civilisation, with Clark revelling in the lines that can be drawn across genres, ages and mediums.

For Clark, high culture and life were one and the same, writing in Upper Terrace House: ‘life is more agreeable when the objects which surround us have been made with love and made to please’. For many it will be precisely the paradox that this culture was delivered to a mass audience by such a blue-blooded figure, that causes discomforting viewing. What is evident, however, is that as a relentless campaigner for making art accessible, Clark’s traditionalism was coloured with a sincere humanist drive and belief in the moralising power of art and its capacity to make us feel.

His patronage of the English Neo-Romantic artists featured here such as Henry Moore, Victor Passmore and Graham Sutherland encapsulate the overarching message of the exhibition: of Clark’s fear of the fragility of the national heritage in the face of modernity and the threat of Nazi occupation. The dark works of Piper and the haunting heavy forms in Moore’s Sarcophagus, speak of nature coloured by darker social preoccupations.

It was from these anxieties, that culture was under threat unless actively promoted, that Clark’s 1969 TV series Civilisation – his most successful attempt to popularize art history– sprang.

Other initiatives are evidenced in his eleven year posting as Director of the National Gallery where his principles were from the off of a democratic creed. His first move was to introduce electric lighting so that the pictures could be seen in the afternoon and evening and he was the first to hang paintings by Manet and Cezanne– a radical move for the time.

It was during World War II however, that his strong will really came into its own, when he instigated the safe relocation of the collections to Welsh mines and established a programme of monthly exhibitions in London. Likewise, during the 1940s he sustained wartime morale with Myra Hesse’s piano concerts in the gallery.

As a harbinger for the late openings of museums and art galleries in our current times, the recordings, which resonate around this show, still seem exceptionally relevant. His efforts to preserve creative energy was not only in his public engagement projects but also extended to the artists themselves, with the founding of the War Artists Advisory Committee. For all the traditionalism, Clark emerges as something of a new-age Renaissance man.

Indeed, with our modern drive to conceptualise and justify art and curation, Clark’s nostalgia, fustiness and eclecticism is almost refreshing. Clark’s documentaries are easily accessible, packaged and distributed; less easy is to swallow is the ultimate fallibility of many of his purchases both in terms of provenance as well as taste. How can someone who demonstrates such an acute eye– in distinguishing between a pair of Leonardo red chalk drawings of a nude man by the copy being shaded “the wrong way”– also make such errors as the identification of four small panel paintings as to be by Giorgione that are now attributed to the little known Andrea Previtale? Even his Michelangelo is wrong.

Taste and failure is, however, what makes us human and it is this that ultimately drove Clark’s campaigning, writing and patronage. There will inevitably be allegations that the show lacks resolution and coherent lines of argument, and that its high percentage of wrongly attributed and ‘bad’ work are a detriment to Clark’s reputation.

Nevertheless, to remove his attic-y acquisitions and to erase the fact that much of his sharing of ‘Civilisation’ stemmed from his ability to possess it, live with it and display it – with the delight of arbitrary formal parallels – would be to do as much a disservice as to simply display his films and books. You can’t have culture and you certainly can’t have Kenneth Clark without the art.

By displaying his work in all its (often ghastly) glory, Tate also gives us a glimpse at some rare pieces of our cultural heritage and reminds us of the importance of art history and the individuals who have defended it. Where else could one see Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘Christ Mocked’ alongside Cezanne’s delicate drawings of his son and the astounding ‘Le Chateau Noir’?

Indeed, love them or hate them, the sub-show devoted to the powerfully dark work of the war artists is worth a visit in itself. In comparison to other great collectors and cultural pioneers such as Samuel Courtauld– who was also renowned for living with his acquisitions and collecting with personal sentiment, rather than ascribing to popular taste– Clark conspicuously fails.

Exiting, however, past Phyllida Barlow’s grotesque cardboard assemblages that converse with the classical architecture of Tate’s cavernous masonry, it strikes me that there is also something rather wonderful about a portrait of, not a movement, but rather a man and his art laid comprehensively bare – warts and all.

As I stand humbled amidst Barlow’s messy monuments, a feeling of reverence creeps over me. Sometimes an unashamed declaration of wrongness, a declaration of that ‘so passé’ emotion of love, can be exactly what civilisation needs.

Main image:

Paul Nash

Battle of Britain 1941

© Imperial War Museums

Clarke photo:

Kenneth Clark in front of Renoir’sLa Baigneuse Blonde (pl.1), c.1933 Private collection

Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation

20th May- 10th August 2014-05-28

Tate Britain