[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]B[/dropcap]y the 27th December, it’s more than likely that the drab internode of the festive perineum has left you feeling a little like you’ve inadvertently fallen into the k-hole.

Turns out though, that every raver’s favourite cat anaesthetic has some beneficial human applications.

At its best, the drug ketamine relieves depression within two hours and its beneficial effect on patients may last a week. At its worst, ketamine, the party drug “Special K,” is addictive and may send recreational users into hallucinations and delusions. Some have experienced disorientation that they call the “K-hole.”

Because of the potential for misuse and addiction, explained researcher Daniel Lodge, Ph.D., of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, “You have a novel, highly effective treatment for depression, but you can’t give it to people to take at home or on a routine basis.”

Antidepressants usually take at least two weeks to show any effect in the patients they help, and not all patients benefit. If a drug were fast-acting and provided sustained relief from depression, the risk of suicide among patients would be reduced.

The problem with ketamine is that the drug acts on receptors located throughout the brain, making it difficult to control its effects.

Finding an answer

Using state-of-the-art research techniques in rats, Dr. Lodge and colleagues from the Health Science Center’s Department of Pharmacology identified a brain circuit that brings about the beneficial effects of ketamine. The circuit sends signals between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. The researchers found that activating the circuit in rats causes antidepressant-like effects similar to those caused by ketamine, whereas preventing activation of the circuit eliminates the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine.

brings about the beneficial effects of ketamine. The circuit sends signals between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. The researchers found that activating the circuit in rats causes antidepressant-like effects similar to those caused by ketamine, whereas preventing activation of the circuit eliminates the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine.

“The idea is, if one part of the brain contributes to the beneficial effects of ketamine, and another part contributes to its abuse and effects such as hallucinations, now we can come up with medications to target the good part and not the bad,” said Flavia R. Carreno, Ph.D., lead author of the study.

Identifying this mechanism now gives scientists a target, Dr. Lodge explained. “The next step is finding a drug that interacts selectively with it. And we have some ideas how to do that.”

Source: Eurekalert/University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

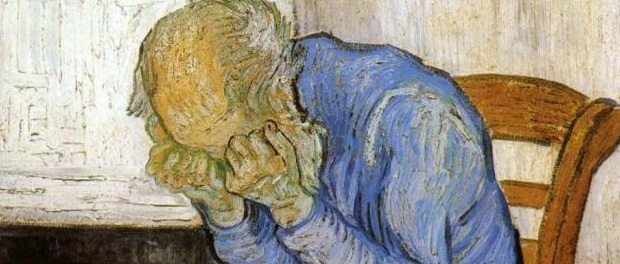

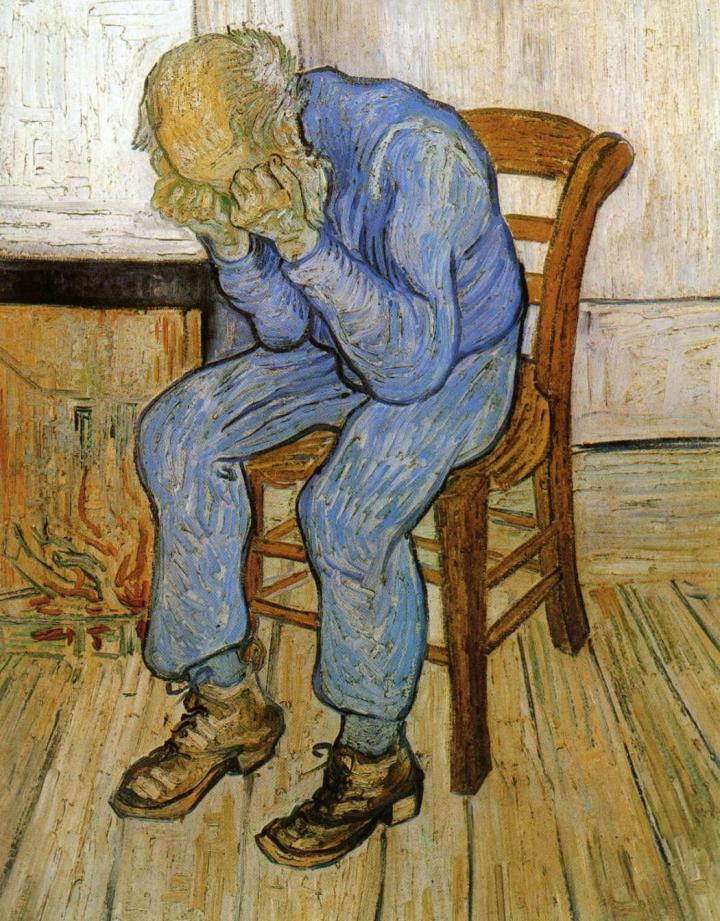

Image: Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Old Man in Sorrow (On the Threshold of Eternity), Public Domain.

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.