Late Rembrandt at the National Gallery

‘Let us go then, you and I…’

– T.S. Eliot : ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’

Understanding what it is to be – and what it is to not be – is a fundamental facet of being human. A consciousness of mortality is hardwired into our psyche. From Lacan’s mirror phase (that moment we first recognize ourselves) onwards we begin a lifelong narcissism that develops as we grow older, compounded by the added dimension of memory. As adults, we see not only the self of now, but all the selves that have been left in the past, a scattering of mini deaths. Viewing one’s own face is quite unlike viewing another. It is to look out and to look in. [quote]A piece of prose, theatre or film

moves through time with narrative drive.

A painting is poetic, in that it moves

around and through time[/quote]

How to translate this mirror image into paint on a canvas? A painting records time in a way quite different to a photograph. To take a photograph is to kill a moment, to slice a chunk of light out of reality and trap it in the room that is a camera. A painting is a microcosm, or at least an analogy, for life itself. A piece of prose, theatre or film moves through time with narrative drive. A painting is poetic, in that it moves around and through time. It is the expansion of a moment and the accumulation of memory. Rembrandt’s late self-portraits articulate this reality.

Consider ‘Self Portrait at 63 (1669)’. We can see Rembrandt’s hand in the marks laid, sense the multiple twists and turns as the paint is moved and shifted across the surface. We don’t need x-rays and cross sections of the surface to see the build up of layer after layer, almost geological in its accumulation. The intensity of looking is clear in the marks laid, covered and corrected. The painting speaks of the time invested for it to come into being. All of this time is flattened and then held in the paint, as if what is depicted is not a single moment but a span of singular experience.

A painting also records our time. Contemporary imagery is largely designed to be consumed with a frenetic immediacy. Rembrandt’s paintings demand quite the opposite; the complication of mark making and stimulus require – and reward – lengthy viewing. Multiple viewings are also rewarded, as each of these visits is present and recorded in the surface when we view the painting again. A painting such as this is a mirror that captures all the time we have spent with it, and then reflects it back at us.

[NG221 Rembrandt (1606-1669) Self Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669 © The National Gallery, London]

Rembrandt’s paintings go beyond surface. Think of his paintings of a cow carcass, an animal hung at the abattoir, open to present the full architecture of its body to the world. Rembrandt’s self portraits do the same, but in place of the surgeon’s knife is the non obtrusive surgery of vision. He presents us with flesh rather than skin. De Kooning famously stated ‘flesh is the reason oil paint was invented’, and perhaps only Titian and Rubens can match Rembrandt for celebrating this truth.

Skin is the mask present in the mirror. Flesh is everything underneath: the blood, the organs, the liquids and solids that make up the mechanics of the human machine. Oil paint holds all of these states: broken down with spirits it splits and shifts like blood, built up with media it is the sticky in-between state of an open wound, we move it around as a thick buttery substance like a surgeon with an open body, then as it dries it stitches itself up.

That Rembrandt’s depiction of flesh reaches its height in the late self-portraits and the paintings of a bull carcass is no coincidence. In both are meat and death. His late self-portraits are sculpted in hollowed-out eye sockets, pockmarks and archeological planes of worn skin. The nose in the ‘Self portrait at 63’ is a flustered red. Flesh for Rembrandt is a play of opposites, a rich red tone sat next to passages of grey green, flicking highlights of yellowing white against pinky purple pulls of skin. Complementary colors and played through and against each other, opening up the full spectrum of colour and tone.[quote]these images are about more than

surface appearance. They are an

intellectual pursuit of what it is

to exist and age [/quote]

Paint, for Rembrandt, is a complex signifier, capable of a multiplicity without contradiction. Paint as paint, paint as time, paint as flesh. Throughout his late works is a preoccupation with paint as light. Chiaroscuro is cited as a kind of catch-all term to describe Rembrandt’s use of light in his paintings and etchings. It is certainly true that extreme tonal contrast is used in his paintings in a similar way to the work of Caravaggio, with large swathes of paintings bathed in darkness and then theatrical focus given to illuminated passages. However, Rembrandt’s light is more than this surface trickery. It seems to exist within the paint itself. It is all in the mechanics of the process and the science of the medium. Thick passages of undulating white paint sit on top of flat dark umbers. Translucent layers of paint are then laid on top. Light pierces these translucent surfaces and bounces back off the white base, and is then refracted in multiple directions on its return to the surface. As such the light seems to come from behind the paint and to be held within it.

On top of this surface are more viscous and opaque passages of paint, where complementary colours are set off against each other. This causes an optical dance across the surfaces, which only deepens the sense of light having been opened up and spread across and through the paint itself. On the surface this light is use as a dramatic tool, to control our attention and the staging of the subject. Beyond this it is an indicator of intellectual and spiritual values. In the late etchings and history paintings these values hold obvious weight. Rembrandt seems to be using light to tell us that these images are about more than surface appearance. They are an intellectual pursuit of what it is to exist and age and a spiritual engagement with what it is to be human and mortal.

Some biographical context is useful in understanding these obsessions. In 1634 Rembrandt married Saskia van Uylenburgh, and soon after began to find significant fame and fortune. A self-portrait from 1640 shows him at the height of his success, aping the pose from a famous Durer painting. The works in the National Gallery show range from 1659 to 1669: the year of Rembrandt’s death.

In the intervening years much had changed. In 1656 Rembrandt was declared bankrupt. Saskia and Rembrandt had four children, three of whom died shortly after childbirth. Only their son Titus survived, but when he was only a year old, Saski died in 1642, aged twenty-nine. Rembrandt’s lover Hendrickje Stoffels moved in (officially as his housekeeper) in 1647. Rembrandt was able to live off his son’s inheritance throughout this time, but a clause in Saskia’s will meant this was on the condition he did not remarry. In 1662 Hendrickje died.

This is the sanitized version of events. The cruelty of these external factors were exacerbated by internal personal failings. Soon after Saskia’s death Rembrandt hired Geertje Dircx as a wet nurse for Titus. He would later promise to marry her. The acrimonious breakdown of the relationship led to a lengthy and complex legal and financial dispute. Most historical and fictional depictions of Dircx cast her as one of two opposing archetypes – hysterical lover or calculating blackmailer. Legal records show Rembrandt requested Geerjte was imprisoned in Spinhuis, euphemistically called a women’s correction house. Historians have labelled the ‘house’ an asylum for the mentally unhinged.

Furthermore, in 1654 Hendrickje became pregnant out of wedlock, and was held up in front of the church council for sinful living. She was banned from receiving communion for ‘committing the acts of a whore with Rembrandt the painter’. Rembrandt is generally pardoned in accounts because of the bind in Saskia’s will preventing him marrying Hendrickje. In 1655 Titus turned 14 and became legally entitled to make his own will. Rembrandt was made the sole heir, allowing him to access the money Saskia had left unconditionally. Yet still he did not marry Hendrickje, and in 1662 he sold Saskia’s grave to raise funds.

The Rembrandt in the paintings at the National Gallery, then, is a man who suffered: as a victim of unfortunate tragedies, and as a result of personal flaws. He was capable of cruelty and foolishness.

We presume such painters to be masters of capturing the moment, or at the most the moment in flux, but might these late self-portraits contain all of these human and historical complexities? Might a painting be a record of an entire life? Certainly if we are given the context it is easy to see the painting through Rembrandt eyes, as if we are the other side of the mirror, and reflected back at us is the full emotional weight, human baggage and expanse of time that has preceded that moment.

But to do this is, to some extent, to puppeteer a painting through context, as if performing an act of ventriloquism in which we can feed the textual history through the eyes, mouth and ears of the image. This performative projection of what came before is effective, but in reality it is about being aware of what led to the image rather than what the image holds. For the image holds none of this.

Painting is about loss, and the late self-portraits are mournful elegies to this. All that has come before this moment has led to it, but is erased and no longer present. It is willful to try and find it.

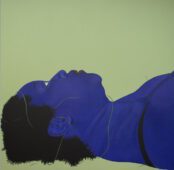

Rather than thinking how the pictures look back it is instrumental to think how they look forward. Rembrandt looks in the mirror and sees his double, sees the physical and psychological weight of age and his life.

Looking back is not Rembrandt but his double, and our doubles are often messengers of our mortality. Which is to suggest the late self-portraits are hymns to what is means to be human, and therefore conscious of this mortality. Painting deals with such messages perfectly because it exists in the liminal space between being and not being.

The ways in which the paintings can be read are two-fold. The first is a context-informed understanding, which sees a painting as capable of holding and communicating the entire complex history of Rembrandt’s life. In opposition to this reading is an outward, forwards-looking interpretation, which sees the paintings as contemplations of the nearness of death.

Combining these double readings it is easy to see why people have looked to compare the late self-portraits with great literary characters at the end of their lives. Shakespeare’s Lear is often cited as a comparison, in particular the ‘Blow winds’ speech of the storm scene. But the late Rembrandt self-portraits are in total opposition to Lear. The storm scene speaks of existential angst, a scream in the face of what it means to exist and to die. It is a desolate, maddening mourning of our passing insignificance and a desperate attempt to hold onto control and meaning. This pace, noise and scale are absent in Rembrandt.

In their place is utter silence and stillness, the intense introspection of being sat in a small room recording your own features and isolating yourself from everything else. Both are dramatic considerations of mortality, but one looks in and one looks out.

A far better model is Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, a poem that has inspired much analysis and interpretation. For me, it is about a man at the end of his life, going on a journey with his double, filtering all that has gone before as if through a film-lens, or as Eliot puts it ‘to throw nerves like patterns on a screen’. It is about watching a life go past, and then readying for the moment of letting go.

This circles back to Rembrandt; the sense of his paintings as rooms; the self portraits records of flesh breaking down, expressing its transience and corporeality; of paint as a record of time; and of the late self-portraits as paintings holding light. It is as if Rembrandt is reminding us that paintings and bodies are rooms. They are spaces we occupy, filled with matter and luminescence, but ones we must eventually exit, and turn out the light.

Rembrandt – The Late Works is at the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square until January 18.

Sidebar Image: © National Gallery, London

[button link=”http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/rembrandt-the-late-works” newwindow=”yes”] The National Gallery[/button]