[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]Y[/dropcap]our name is Adam. You don’t see death, you feel it. Your name is Adam. You are deceiving and being deceived.

You are a witness and a story-teller. Your name is Adam and you are making history.  You are being killed and the media presents your murder as a strike. You don’t see death, you scream it. You are surrounded by bodies wearing your same uniform, wounded and destroyed. But the bodies vanish into data, and the decision of how your story is to be told is tied up to a certain political agenda; an agenda that calls for either enthusiasm or despair.

You are being killed and the media presents your murder as a strike. You don’t see death, you scream it. You are surrounded by bodies wearing your same uniform, wounded and destroyed. But the bodies vanish into data, and the decision of how your story is to be told is tied up to a certain political agenda; an agenda that calls for either enthusiasm or despair.

You become marginalised, categorised, and eventually forgotten. When you are injured, they say you are disarmed. And when an enemy soldier is killed, they label him as cannon fodder. This alteration, not only in language, but also in the content of war images, shifts the moral perception from disastrous to perhaps necessary collateral damage.

Visual warfare plays the same game today as it did a hundred years ago during the First World War. For today, we live in a culture fostered with indifference. The media serves us just enough horror to satisfy the amount of compassion we are willing to share. We are insulated through distance and unfamiliarity. Yet images taken during warfare hold a certain power that is both cruel and just. When you see a picture of someone dying after gunfire or bombing, within that frame of space and time, they will forever be both dead and alive.

Is it wrong to look at these images? Are we responsible? A photograph, for example, holds a truth; a truth that has been chosen to be shown to us. Selecting certain episodes from a story can altogether create another story. And hiding certain images from the full picture can altogether change our perception.

We seek to find the truth through witness statements and recollections. Bearing in mind that these spoken words, choice of imagery, or artistic gestures, carry the burden of the experience; the trauma, the pain, and the sentimentality. And in matters of war, if we are not given access to all information, if anything is being manipulated or censored or hidden, then we are being lied to. It is inevitable that even the artists sent to represent life on the front line are both deceiving and being deceived. And perhaps it is for this reason that Russian artist Kazimir Malevich developed Suprematism; to denote the abstractness of his present situation and the future; the abstractness of war, tragedy and untruths.

A Game in Hell. The Great War in Russia, an exhibition held at The Gallery of Russian Arts and Design in London provides insight into the silent period of forsaken Russian achievements during The Great War  and in the events leading up to the October Revolution in 1917. Bolshevik doctrine called for the censorship of all propaganda glorifying Russian military attainments during the War. Banning these posters, lubki, and photographs from mass circulation strengthened their position nonetheless. This exhibition looks at the tragic irony of revolutionary Russia and hence opens our eyes to how wartime propaganda is a game played by power.

and in the events leading up to the October Revolution in 1917. Bolshevik doctrine called for the censorship of all propaganda glorifying Russian military attainments during the War. Banning these posters, lubki, and photographs from mass circulation strengthened their position nonetheless. This exhibition looks at the tragic irony of revolutionary Russia and hence opens our eyes to how wartime propaganda is a game played by power.

The exhibition is curated by Prof John E Bowlt, Dr Nicoletta Misler, and Director of GRAD, Elena Sudakova. Most of the material on show comes from the collection of Sergey Shestakov who hopes that they will “encourage us to reconsider the relations between Europe and Russia… and remind us of the real threat of future world wars and their consequences.”

Just like Rudolf Bauer’s non-objective artwork, these exhibits feel as if they have come out of imprisonment. They carry a resonating, multi-faceted significance.  Troops were losing their lives in the trenches, artists were developing their art at home, and those who once designed patriotic posters were soon to give up God and the Tsar and offer their talents to the Bolshevik cause. Photographs taken during that period are relatively polite and reserved, showing Russian advancements in machinery, aeroplanes, and abstract aerial landscapes rather than the brutality of four million deaths.

Troops were losing their lives in the trenches, artists were developing their art at home, and those who once designed patriotic posters were soon to give up God and the Tsar and offer their talents to the Bolshevik cause. Photographs taken during that period are relatively polite and reserved, showing Russian advancements in machinery, aeroplanes, and abstract aerial landscapes rather than the brutality of four million deaths.

The work of Natalia Goncharova, however, manages to preserve the feelings associated with the war; ‘primitive’, powerful, and as Bowlt and Misler note, ‘apocalyptic’. She was able to translate the emotions of those dying at the front, not through satire or illustration, but through ambiguous mysticism.

So perhaps photography can hide brutal violence and horror, and perhaps the state can omit information, delete footage, ban books, hide artwork and burn posters, but the transfer of an emotion, from artist to viewer, from present to future will always remain. And this exhibition, has rendered clear that the lies and games of wartime propaganda can change our perception of history but not our reaction to it.

“Such a strange time it is, my dear!

They cut off the smiles from lips,

and the songs from throats!

We must hide our Emotions in dark closets!

They barbecue canaries

On a fire of jasmines and lilacs!

Such a strange time it is, my dear!

Intoxicated by victory,

Satan is enjoying a feast at our mourning table!

We must hide our God in dark closets!”

– Ahmad Shamlou

Featured Artworks (in order)

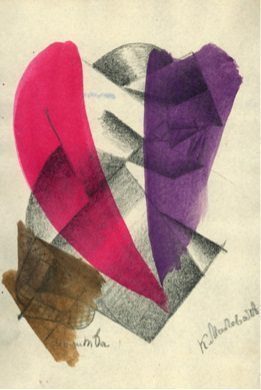

Kazimir Malevich, ‘Prayer’, illustration for Explodity by Aleksei Khruchenykh

Illustration for the Futurist book Explodity, which featured drawings by both Olga Rozanova and Kazimir Malevich

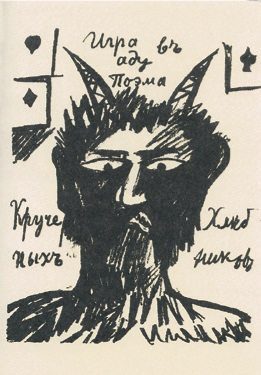

Natalia Goncharova, cover design for A Game in Hell by Aleksei Khruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov

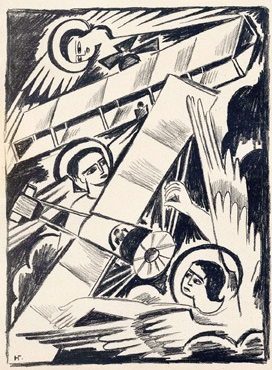

Natalia Goncharova, ‘Angels and Airplanes’, lithograph, 1914 One of fourteen lithographs in the folio Mystical Images of War, using Biblical imagery to explore the conflict

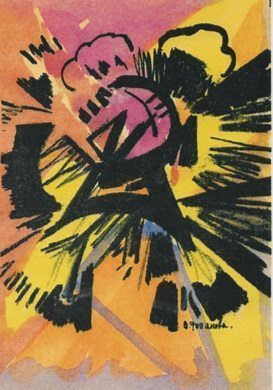

Olga Rozanova, ‘Explosion’, illustration for Explodity by Aleksei Khruchenykh

(Image shows how Futurist artists were already exploring notions of conflict and violence before the start of the war.)

[button link=”http://www.grad-london.com/” newwindow=”yes”] GRAD : Gallery For Russian Arts and Design[/button]

Faten Hakimi, Artist and Fine Art Consultant, MA Fine Art City & Guilds www.fatenhakimi.com