What if we could live forever? In the middle of Basel, a city steeped in pharmaceutical industries and life sciences, rots an abandoned clinic that once sold immortality. Aged by graffiti and office decay, haunted by the spectres of a terminal species, it prompts us to ask ‘what if?’.

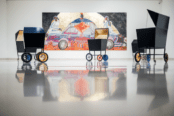

The desolate facility has a reception, control room, lab, surgery, recovery room, and a long misty corridor leading back to the foyer under a wry neon sign beaming ‘welcome back’. Scrawled graffiti covers the walls. Some, riffing on the theme of life extension, comments on the failure of eternity, emphasising what came after. And what promises? Each trashed room contains a different take on what life extension means; the promise, what it’d be like, the research, the process, and contemplations of life extension.

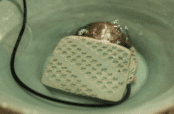

An empty reception sets the premise of the show; the facility is abandoned because with eternal life ‘of course, we no longer need hospitals. That’s why these buildings are abandoned and in decay’ [exhibition notes]. Many of the ceiling tiles have fallen down, broken screens flicker, amplifying the already creepy atmosphere of medical facilities. In a corner is a lurid green model turtle ‘Adwaita’ (who passed away in 2006 at 255 years of age). A memento mori of a long life, as lived in captivity.

In subsequent rooms, viewers are shown a mixture of real and imagined testimonies of current science advancements and informed conjecture. A series of movies play In the control room, illustrating what immortal lives might consist of; a Japanese teenager claims she is over a hundred years old, a rapper considers what life is without an expiry date, twin pensioners argue about self improvement, and a mother and daughter communicate across generations.

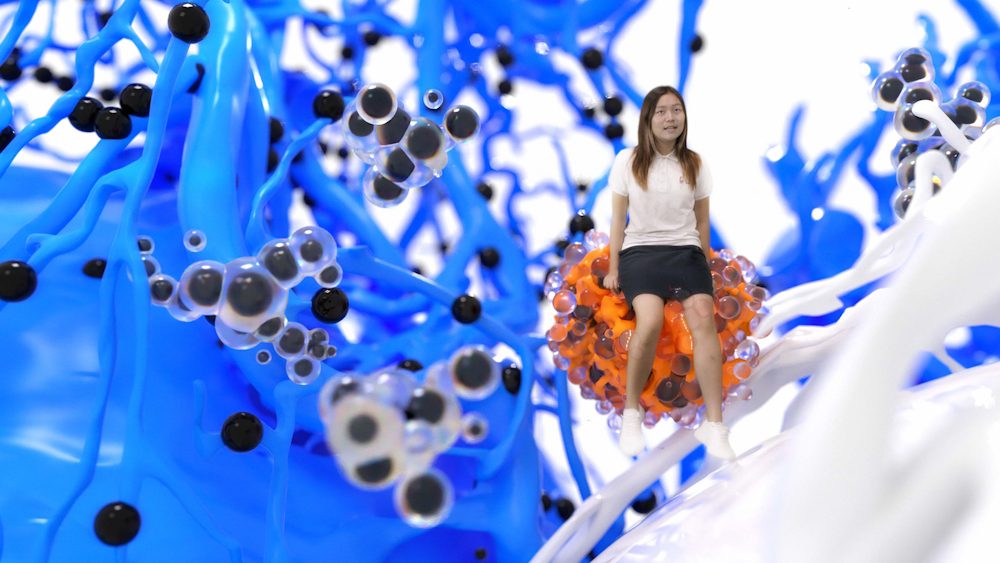

In the lab room we see molecules, genes and atoms; the building blocks of life. In the surgery room, a spectral woman engaging in an out of body experience ‘wanders through moments of her life with mortals before they die out’. (In the narrative of the exhibition, the mortals have since become extinct). The recovery room, appropriately, provides a series of comfy gurneys where interviews with contemporary researchers present the 2024 state of life extension research: the ‘reality amongst the alternate reality of the show’.

The creator of this immersive narrative is the Swiss-German polymath Michael Schindhelm (1960), whose varied career has seen him publish, curate and organise across theatre, tv, art, and quantum chemistry (MSc). Highlights include stints serving as the founding director of the Dubai Culture & Arts Authority in Dubai, UAE, and prior roles as the General Director of the Berlin Opera Foundation (2005–2007) and as the Artistic Director of Theater Basel (1996–2006).

With the End of Ageing, there is a sense that Schindhelm is culminating his various interests in science, art and theatre across a thematically vast two-part exhibition series titled Bids for Survival. A collaboration with the KBH.G, the show itself casually nods to exhibition partners such as Novartis, University of Basel, Biozentrum Basel, Institute for Ophthalmology, FHNW HEK, and the media studio iArt. The references lend veracity to create a story that has several entry and exit points. Raphael Suter, Director of KBH.G, explains: ‘For the first time KBG.H has invited a curator to work across a project involving two exhibitions. Michael Schindhelm’s background in shaping cultural narratives brings a unique perspective to the exploration of longevity, seamlessly blending science and art to provoke contemplation on the implications of escaping biological mortality.‘

In the flesh, there’s a lot going on in the show. At any given time and in any given room, multiple sensory inputs compete for attention. It would be an achievement simply to create the laboratory complex, let alone the additional layers of audio and video media that impact the participant. The graffiti and distressed walls felt genuinely worn in, and the addition of dry ice and blinking lights creates a fitting atmosphere to accentuate the imaginary landscape of a dying utopian dream.

This sort of exhibition requires an active attention, and several lengthy passes to separate the varying stories on show. The first pass is typically to focus on the media, the audio stories, the films, the academic lectures. The second tries to consume the idea of the ruined clinic as a story in itself, asking reductive questions. Who made the graffiti in Schindhelm’s future vision? Disaffected mortals? The final youths of an undying society? Would a clinic such as this, in a city, become abandoned? Why not reused?

The final perspective, and the most emotionally affecting, is the aesthetic feel of the exhibition. The ambience of the show, when one shuts out the filmed stories and academic lectures, arises in quiet moments. The melancholy of humanity’s obsession with life extension and youth, practically universal, comes in waves of confrontational philosophical judgements. Surely, not-dying isn’t enough to qualify as living. The abandoned clinic, with its cloying formica and grubby screens, suggests that death is a central part of a human cosmology.

It’s a thought suggested by the featured academics, who argue that life extension now (and perhaps forever) is about consistent healthy living rather than a magic pill. Similarly, the rapper’s testimony about the meaning of an endless life has echoes in the half-life remembrances many people still harbour after lockdown. The familiar idea, of being alone with our lives forever and ever, suggests that on a societal level we need to find an enlightened position that includes everyone, if only to save ourselves.

The End of Ageing succeeds in presenting a deep myriad of visions of what immortality might mean, encapsulating both scientific and philosophical implications in a rigorous fashion. However, it struggles to provide sufficient space for attendees to really cross the intellectual threshold and appreciate the exhibition’s considerable artistic achievements in a personal way.

The key stumbling block is that at various points it comes across as too expository. The message of numerous videos explaining life extension and its implications might have been more evocative if suggested via supplementary material; case notes scattering the surgery floor, sales pamphlets stacked in the reception, haunting robotic tannoy calls requesting a doctor’s presence for a human species now extinct, or an augmented reality app allowing the explorer to see the clinic in its heyday. The latter would offer a suitable remove to watch videos and hear testimonies without negating the (ironically) morgue-like atmosphere of commercial immortality.

From an audience point of view, it’s common for installations to situate the viewer as an investigator, piecing together the message by reading creative choices as clues to the artist’s intentions. The End of Ageing also presumes this, but would more informational opacity increase the dynamic tension in line with the artist’s vision? Perhaps. Schindhelm’s ambitions are beyond anything so simple as having a primary narrative from which invented and actual information branches out. And though such approaches have been used successfully by multidisciplinary artists such Tai Shani, one senses that Schindhelm is breaking the fourth wall on purpose. During a conversation, he intimated with a wry smile that his creation, a rumination on life extension, in Basel – the home of pharmaceutical and medical research – creates a contextual frisson that is hard to miss.

Across the road from the exhibition is the Clarunis Universitäres Bauchzentrum Basel Standort Universitätsspital (university hospital), an imposing complex renowned for medical advancement. Inside, academics, medics and researchers undoubtedly work for the benefit of all people. However, there is an element to all altruism that assumes a subjective good. One generation’s ethical standpoint can be cast in a very different light as societies, lives and new conceptions of humanity evolve with technology, increased economic division and environmental threats. Schindhelm’s exhibition heightens the intersection between these presuppositions.

What we currently know, and where our dreams of immortality might take us, The End of Ageing contains the message that, rather than easy answers, it is from an appreciation of the multiplicities of future vision that we can start to put together a plan — one that doesn’t merely extend our current structural societal problems.

As always, a step forward is rooted in where we currently stand.

Bids for Survival: The End of Ageing will be open to the public from 3 May to 21 July 2024, at the Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger | KBH.G, as well as on a dedicated digital platform from July 2024.

More info: www.kbhg.ch

Photos courtesy of KBH.G. Installation shots from The End of Ageing, Basel, 2024

Writer and academic Cartagena works in the arts polishing bios and gallery notes in the pursuit of clarity. He also lectures, though with enough opacity to impart wonder.