Complementary, alternative, gimcrack — the Western medical/surgical tradition has often struggled to embrace elements of healing practice that fall outside of its own peer-reviewed, standardised ruleset. Understandable; we’ve come a long way since Aristotle, and advances in medicine — which are continuing apace — have come courtesy of a stringency of procedure that errs to the side of caution.

Nevertheless, insofar as it remains within the tolerances of the ‘do no harm’ ethic, the remit of the healer can extend far beyond the parameters of the hospital or surgery. Palliative care, where the end result is in no doubt, often provides a sandbox for therapies which might, in another application, be considered too speculative to be worth the detour from established methods. The terminal patient surreptitiously recommended cannabis to stimulate an otherwise absent appetite; the ALS victim brought to bathe with dolphins; the multiple interventions of the Make a Wish foundation — hope, succour, and the simple provision of momentary joy put flesh on the necessarily bare bones of sterile medical procedure.

‘Hospitals can be such noisy, sterile and unnatural places — often with competing sounds of hospital equipment, no natural light, nor access to plants and green spaces — and so linea naturalis is designed to connect people back to nature by listening to music created from the same plants that their chemotherapy drugs are made from,’ states Dr Helen Anahita Wilson, the composer, sound artist, and pianist behind ‘linea naturalis’ — a musical project using electrical data derived from plants with medicinal and healing properties, made to be listened to by people undergoing cancer treatment.

Wilson, whose own experience of chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy and immunotherapy (as treatment for breast cancer) inspired her research, delves into a branch of possibility that adheres to an established logic: If certain properties of healing plants can be used in therapeutic ways, might there be others that have not yet been exploited? Piggybacking on the methodologies of circuit-bending sound artists to create generative electronic music, the composer steps beyond the chemical properties of medicinal plants and into their electromagnetic signature. Her subject matter is not at all random:

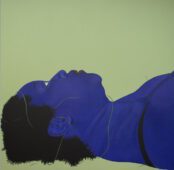

‘Many people are not aware that a lot of chemotherapy drugs are rooted in nature. For example, yew trees were used for many years in the manufacturing of the chemotherapy drug Taxol (used to treat certain kinds of breast, lung and pancreatic cancers) and the beautiful Madagascan periwinkle [pictured above on the release artwork] is used in the drug Vincristine to treat leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.’ — Dr Helen Anahita Wilson.

By connecting electrodes to plants involved in chemotherapy and other anti-cancer treatments, Wilson transforms bioelectrical frequencies and fluctuations in micro-electrical currents from each plant into notes and phrases. She then carefully crafts compositions using these plant-derived musical phrases. Having trained to postgraduate level in both Western and Indian classical musics, she uses compositional techniques from both traditions to compose music from the biodata extracts.

‘This music was designed and created especially for people going through treatment, although anyone can listen to it and enjoy it’ states Wilson. ‘Not only is all the music made from plants used in cancer treatments, I’ve also incorporated recordings of birds and gentle rain which were triggered by natural plant bioelectricity. You’ll also hear plant-derived melodies played by a harp, strings, and some beautiful electronic instruments.’

It’s certainly a step or two beyond the swirly synthwash whalesong typical of the high street hippie headshop. At best, Wilson may help to break ground on new therapies. At worst… it will do no harm.

linea naturalis (we are all bioelectrical beings) by Helen Anahita Wilson is available on all music streaming platforms and Apple Music will have an exclusive Dolby Atmos Mix. Half of profits from this release will be donated to Cancer Research UK and Maggie’s cancer centres.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.