[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]”[/dropcap]Tearaways, layabouts, lesbians, queers, mysteries, and hangers-on. We just sat in the café, waiting. Waiting for another day to kill itself. Every time the door opened we looked up as if we were expecting someone. We wandered from café to café. ‘Have you been to Tony’s? Who was there?’ ‘No one.’”

– Bernard Kops, The World is a Wedding, 1963

Events! If you want those, you’d best stop reading now. This is about sitting and staring and drinking coffee and maybe listening to some music and definitely talking shop. Before the Gaggia machine, before the 2Is Coffee Bar, two of the best cafes in London were on Old Compton Street. Both were down at the end where it meets Charing Cross Road. The Star Restaurant was on the left as you came off Cambridge Circus. It was more of a caff than a café. It was run by a Greek, Andreas. The décor was rudimentary, consisting of greasy Rexine tablecloths and crooked chairs and tables. The toilets were in an alley which led directly onto the street (handy if you were taken short and had no money). The menu was chips-with-everything; there was nothing remotely Greek on offer. Two sausages and chunky chips, a slice and a tea — one and eight pence. The Star was basic but it looked after its patrons. Almost all the musicians gigging in the jazz clubs found an opening, a gig, a plate of chips, some camaraderie and inspiration in the Star. Opposite the Star, at number four, was the coffee shop that was, without doubt, the place to go for the more dishevelled members of London’s artistic community.

Not to be confused with the French pub on Dean Street, the French was ostensibly a tiny newspaper shop selling international papers and magazines. It was a microcosm of the Soho that offers the promise of cosmopolitanism, a constant shifting of identities, a blurring of positions and perspectives, roles, general make-believe; everything really. But, although the newspapers took pride of place, the main business was coffee. The manager was a lugubrious Belgian, Bernard, and he brewed it up in a proper pot. Tea was available but frowned upon. There was nothing edible other than stale croissants under a glass dome on the counter. The French café was Laura Del Rivo’s introduction to Soho. She was 17 when she started going there.

“I had a job at Foyles book shop. In those days Foyles put tables with books outside on the pavement. It was a bit like a street market. My job was to stand in the doorway. I would see the prostitute whose beat was outside Foyles. She had a little, fluffy dog. She looked a bit like Dora Bryan, her lipstick was all over the place; her roots were showing. We always hoped she would get a man but she didn’t. Generally they ran away.”

Del Rivo’s eye was taken by the St Martin’s students from the building next door. The art students were, she says, the acme of glamour. One of them took her to the French. As soon as she crossed the threshold she felt a great sense of peace. “So this is where people like me go,” she told herself. It was a dump, she remembers, but she felt instantly at home. “We didn’t eat anything. But we drank Greek coffee which felt very sophisticated.”

My introduction to Laura Del Rivo took place at her pitch at Portobello Market underneath the Westway. In-between handicrafts and souvenirs, Laura sells ladies’ hosiery and fashions from the 1950s. I had walked past her stall many times, charmed by the jitterbugging dresses and fishnet tights. On her stool, the stallholder was thin and girlish with a bob of silver hair. Her gaze was always in the middle distance, as though dreaming. I was intrigued when someone told me, “She’s a cult novelist, you know.”

When I finally plucked up the courage to introduce myself she told me the reason she looks so remote is because she has prosopagnosia (difficulty in recognising faces). She invited me to her attic flat just off Portobello. It was everything I had hoped it would be. Bare floorboards, painted wooden cupboards and a rainforest of ferns, fronds and yuccas. Books and oils were everywhere; fossils and relics were scattered among them. I was particularly impressed by her lack of a kettle. Amidst a pile of paperbacks, she made me a cup of ginger tea in a saucepan of boiling water and filtered coffee for herself.

The Furnished Room, written by Del Rivo in 1961, was originally described as “an existential bedsitter novel”. The Guardian’s Isabel Quigly found it “extraordinarily unappetising”. However she was gracious enough to admit it contained “moments of grace” and “fashionable echoes” of alienation. Keith Waterhouse must have liked it because he wrote the screenplay for the young independent filmmaker, Michael Winner. His film was called West 11. It featured Diana Dors in a serious role, revealing depths of bittersweet vulnerability. The film, like the novel, was judged to be rather too authentic for comfort.

“We didn’t much go to the pubs because drink was expensive. The generation before us — Dylan Thomas and Francis Bacon — was the drinking generation. Ours wasn’t so much. It was more abstract discussions as well as the usual gossip about who was keen on whom. I didn’t stay at Foyles that long because they used to hire and fire people after a year. Nobody ever stayed there long so it was always a total mess. I next had a job in the office of a coal merchant’s in Marylebone. I would come to Soho when the office closed. It was like an informal club.”

It was a club with some extraordinary members, most of whom were known to Del Rivo. “There was Countess Eileen. She was an old lady, quite bent over, and generally carrying a bag full of shoes. Clothes were scarce those days, so a crowd would gather round her to see what she had. Sylvia Gough, the diamond heiress, was there, too. She had been a model for Augustus John and lived with a famous murderer in Fitzrovia. Sylvia was very elegant. She would say, ‘Darling, I haven’t eaten for three days. Buy me a gin.’ Iris Orton the poetess, she spluttered when she spoke and always wore a cloak. Ernest the Astrologer, Ricky the Poet, Lesbian Lorraine… they were like fixtures in the café.”

Del Rivo found herself among the last guard of the Bohemians, a group that ensured that in post-war rationed London the Romantic movement was still paying tribute to a few grand years in which the British rivalled the Quartier in artistic licence and extravagant creativity. King of this particular Bohemia was Ironfoot Jack, a mountain of a man with a coil of black hair slithering down his shoulder like a pet snake. His right leg was shorter than his left. To overcome this he wore a surgical boot with elaborate metal scaffolding supporting the sole.

As a lad, it was said, Jack had lived with the gypsies. In his youth he worked sideshows and spectacles in circuses all over the country. In his prime he ran a theatrical boarding house, two Soho nightclubs, a School of Wisdom, and a Children of the Sun materialistic religious group that worshipped at a commune in Camberwell.

Professor of anything, hawker of cheap jewellery, lucky charms, and yogic perfumes, Ironfoot Jack could be whoever you wanted him to be and could give six different versions of how his foot met its calamity. Each one was more glorious and grandiose than the last: a shark-bite while pearl diving in the Seychelles; an avalanche in Tibet; a bloodhound’s bite; mauled by a lion; shot while smuggling; run over by a car while saving the life of a child.

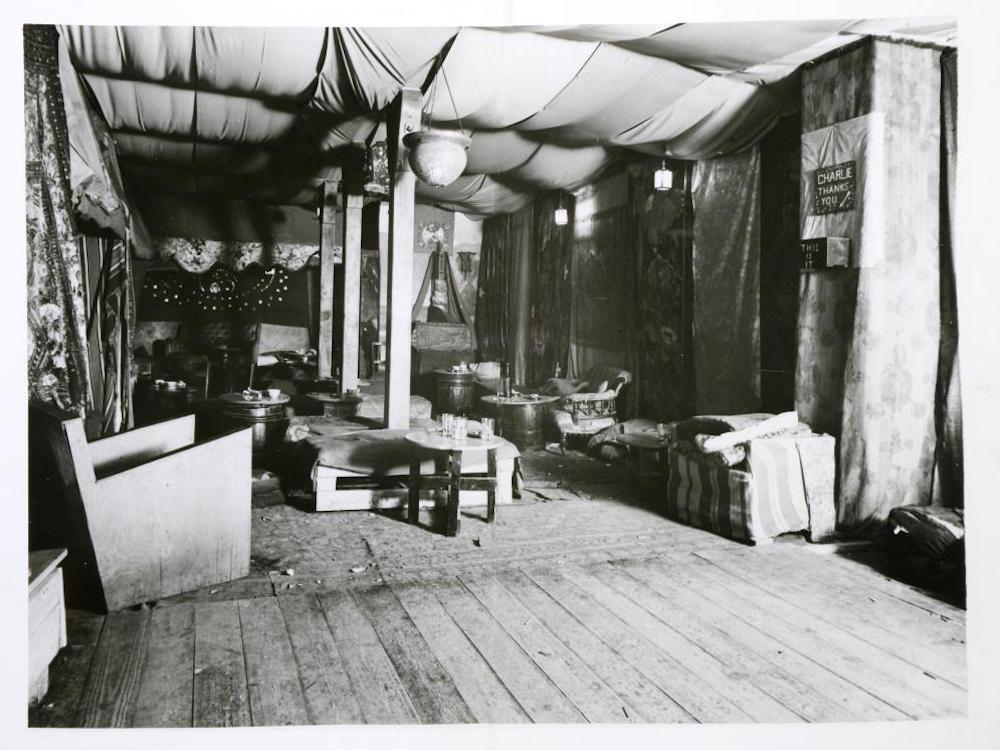

But Jack’s genu-wine feat which earned him national notoriety and a bundle of newspaper clippings took place in 1933 when he poured Soho sauce over Endell Street, across the great divide of Charing Cross Road. The Caravan Club came on the back of two nightclubs Jack had opened on Wardour Street, the Jamset and the Cosmopolitan. The advertisement stated it was ‘London’s Greatest Bohemian Rendezvous said to be the most unconventional spot in town’ — a code phrase meaning homosexuals were welcome. The ad promised, ‘All night gaiety’ and ‘Dancing to Charlie’. The police were duly alerted. Soon after opening, the club was raided and multiple arrests were made.

In court, a constable stated that the women present were of the “importuning type”, and that he had entered into conversation with a man named “Josephine”. A Constable Mortimer testified that, “Men were cuddling and embracing.” He, too, had met two men who introduced themselves as Doreen and Henrietta. When asked if these men were present in the court Mortimer replied, “Doreen, no. Henrietta, yes.” The judge had to silence the laughter.

Dressed like a 19th-century savant, the accents of his iron foot and walking stick stumped through the room, causing conversations to cease and heads to turn. Jack’s entrance always had this mesmeric effect, no matter where he made it. Reality became suspended in his presence, and everything became possible.

Not everyone was so enamoured. “There was a side to Ironfoot Jack that I wouldn’t want to touch with a bargepole,” Iris Orton told me. “He was mixed up with all sorts of criminals. But when I knew him he was an old man. I called him Mr Neave. He made just enough money to live on by selling horoscopes outside the National Gallery. Then he would come back to the French café and have his coffee and talk to people.”

Read Pt. II here and Pt. III here

With a background in the arts and journalism, Lilian Pizzichini is the author of Dead Men’s Wages (winner of 2002 Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction) published by Picador. In 2009 Bloomsbury published The Blue Hour: A Portrait of Jean Rhys (BBC Radio Four Book of the Week) and in 2014, Music Night at the Apollo: A Memoir of Drifting, a Spectator Book of the Year. Her fourth book, The Novotny Papers, was published by Amberley in May 2021, and featured in The Daily Telegraph and Daily Mirror’s “Big Read”.

Love it : I remember Iron Foot Jack & the whole piece brings back all my memories of Soho in the 60’s about

which I will be speaking at the Dellasposa Gallery lo with Jo Reed Turner on May 22