[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]ound is a fleeting, elusive, and evanescent thing; even to call it a ‘thing’ misrepresents.

And yet, it’s also one of the most fundamental aspects of human sensory experience. For those with normal sensory abilities, sound is our primary way of knowing the world.

Primary in the sense that sound precedes sight in physiological development (we hear before we leave the womb); primary also in the sense that our ears tell our eyes where to look (our ability to aurally locate sound sources that we can not yet see – behind us, around the corner, on the other side of a wall); primary in the sense that, while we often shut our eyes, our ears are always working (we have no ear-lids); primary again in the sense that it is common for us to be in situations where we can not see (or at least vision is severely restricted) but exceedingly uncommon to be in situations where we can not hear (there’s no common aural equivalent of darkness).

[quote]our ears tell

our eyes where

to look[/quote]

The situation is similar with sound in relation to our other sensory modalities of taste and smell. Only touch, of which we might say that hearing is a physiological variant, is on more-or-less equal footing with sound, with the exception of proximity.

As radiated kinetic energy,  sound is both immense and intimate, vast and infinitesimal. It physically connects us to distant vibrating objects and yet informs us of our closest surroundings. Sound is transformed by everything with which it comes into contact between source and listener – as such, it tells us as much, if not more, about where we are as it does about what is vibrating.

sound is both immense and intimate, vast and infinitesimal. It physically connects us to distant vibrating objects and yet informs us of our closest surroundings. Sound is transformed by everything with which it comes into contact between source and listener – as such, it tells us as much, if not more, about where we are as it does about what is vibrating.

We hear context and environment as much as we hear things. Our location relative not only to sound sources but also to physical features of the environmental context is a prominent aspect of aural perception. Even more so than sight, hearing is inherently spatial in nature.

Sound and hearing are at once both deeply personal and inherently social, simultaneously of a piece with both the sacred and the profane. Many spiritual traditions – including Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, animism, and various ‘traditional’ belief systems – accord a special place for sound, be it the word of god, the harmony of the spheres, the singing into creation of the physical world, or as a means to focus and quiet the mind for communion and/or meditation.

Conversely, sound is also a means to domination, subjugation, and repression; a thing to be exploited, arrayed, and deployed, or else regulated, legislated and silenced. It is both personal and political.

The world is truly a world of sound, and listening is a primary entrée into that world: it helps you orient yourself, understand where you are, and what is around you. Sound is the way in, the way through, and the way out.

Listen.

Listen to the sounds around you, and know your world.

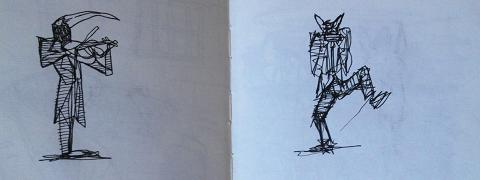

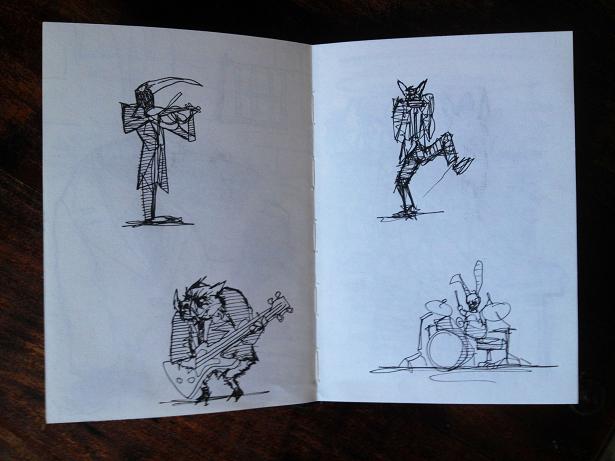

Illustration by Dan Booth

This Make Better Music article was written by Steven M. Miller, in continuation of a series started by Dave Graham.

The words, images and music of Steven M. Miller can be experienced here:

Steven M. Miller is a composer, sound artist, and improviser whose work and interests intersect sound, culture, technology, and the arts. Also an avid photographer, his formal training includes music, audio recording/production, electroacoustics, and interactive media. www.stevenmmiller.net