[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he candle is not lit / To give light, but to testify to the night – Robert Bly

Light still has the power to compel and great art has been characterised by its relationship to that which reveals and in revealing, teaches. If darkness is the unknown then light is the teacher. We are manifest in knowledge and disappear without definition. From these dreamlike, ontological bases creative artists have yearned and probed for millennia and in the contemporary world our fascination with light continues undimmed.

The Luce exhibition at the Daniel Benjamin Gallery brings together two emergent artists, Jemma Appleby and Liz West, around the common theme of light. While in general using such a primordial premise might not be considered selective enough to hold any real meaning, in this instance both artists present novel perspectives and the exhibition itself is a rare example of nuance and depth.

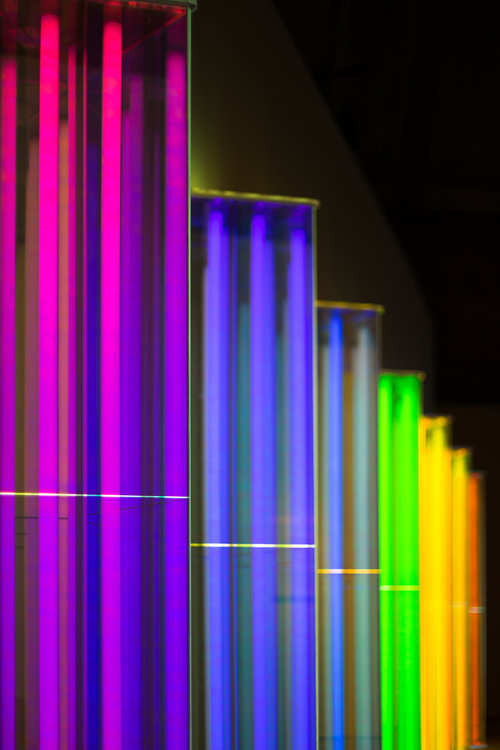

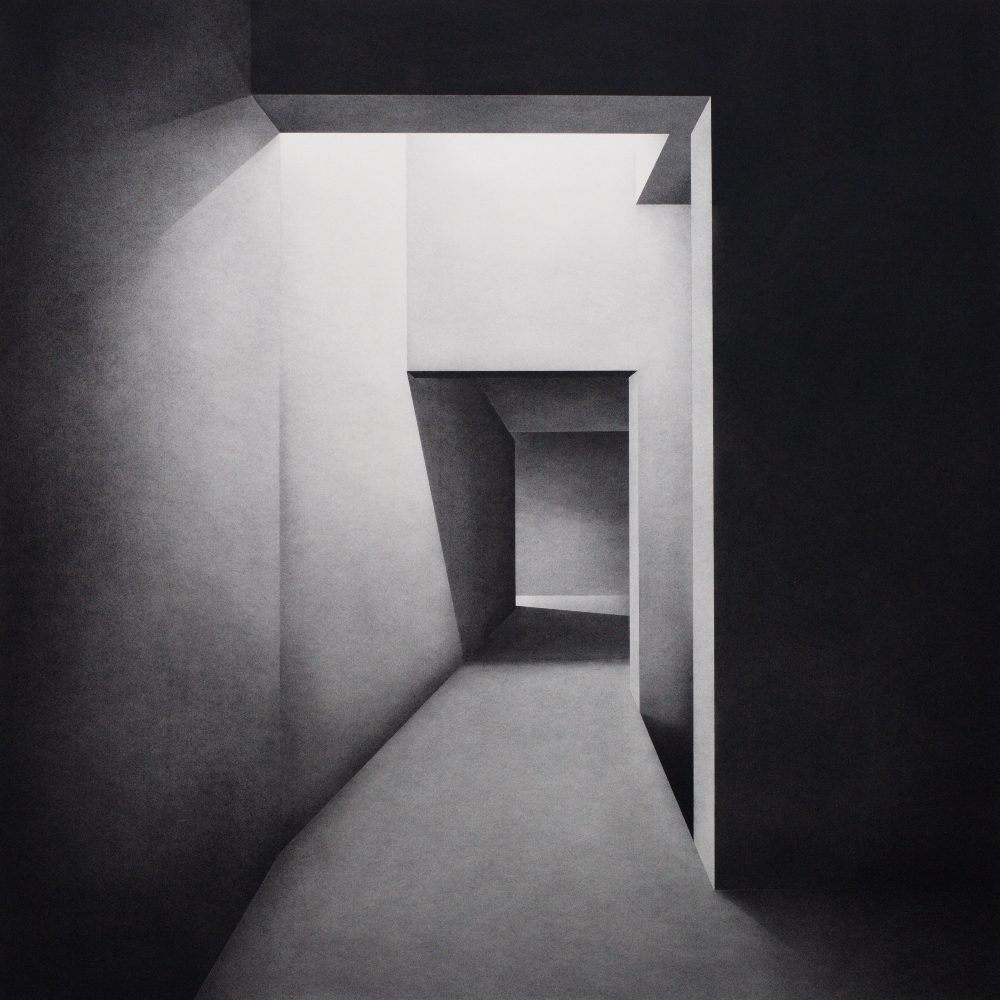

Walking into the Daniel Benjamin Gallery in Notting Hill, the large vertical mirrored prisms of West’s Our Spectral Vision dominate, emanating a bright tubed LED light which reveals a depth of scintillation as the viewer’s position changes how the colours are experienced. Downstairs, Appleby’s precise black-and-white charcoal works describe a number of architectural scenes at once familiar and abstract, compelling and yet distant.

‘Daniel Benjamin Gallery is pleased to present LUCE, a conversation between two UK-based artists and their exploration of the intricate relationship between architecture and light and the human response these two invoke.’ – Daniel Benjamin Gallery

Liz West, Our Spectral Vision (Installation), 2019

Light defines form and in Appleby’s works her emphasis on structure shows how light contextualises objects as shapes. In her monochromatic world the three-dimensional world is simplified as it assumes a mathematical and horological context, the sun’s position marking a contextual point on a static world. The way daylight penetrates and defines the objects it hits is specific to a certain day (perhaps referenced by the titles of her work, i.e. #1211019) so we are viewing a relationship between object and light that is perfect in its distant singular moment. We know we are looking at architectural forms which suppose a human scale however most of the places featured describe interstitial settings: corridors, staircases, portals of various kinds. Places where humans have only a transitory existence through human structures. Places where we are evident but invisible. Appleby’s exquisite pictures, rather than drawings in a conventional sense, are visions of dehumanised human spaces, monumental and beautiful in their graded repose.

Jemma Appleby, #1211019

Jemma Appleby, #1141119

In Liz West’s installation Our Spectral Vision, light describes hope. The projection and interaction of light in her work creates an unnatural sense of wonder; the timbre of light looks artificial but evinces very human qualities. West describes her interest in luminism as drawing inspiration from a childhood epiphany when she connected celebrity and stage lighting with a sense of enhancement. In some way reflecting that in the presence of stage light, an archetype is made manifest through a human vessel creating a hype(r)-being (celebrity) which has artistic immanence by being layered with attention, possibility, and hope. Hope being the projected belief in an ideal possibility emanating from a person. It’s a directional way point for its discoverer; I hope, my hopes, their hope all suggest an end state. West tantalises us that within the baptismal light of her works we are cleansed in the pure light of a child’s fascination with an idol and as the colour temperature varies depending on our position, we are encouraged to feel that our vision and experience of that light is intimate and unique, perhaps insular. Literally, our personal vision lighting the way.

The experience of West’s works cannot be shared exactly; the phenomenon can be described in broad terms as ‘when x colour hits y they make z, which shifts to a when I lean to the left’, however the ability to view each light column is singular. Only one person can exist in one space at a time. The work succeeds by allowing multiple points of access to the piece and whether you are well versed in the history of light art (From Moholy-Nagy to Dan Flavin to Brian Eno) or not, the universality of the personalised experience of hope describes a transcending optimism. Our Spectral Vision could then read as this phenomenon; gathering, specific, shared and yet negating, our experiences are unique but they are not necessarily personal. The term spectral has references to the idea of things distributed on a defined axis, and then the idea of spectre or phantom, which is the experience of something that has no material presence: hope.

In bringing together these two artistic talents the Daniel Benjamin Gallery has shown itself to be a savvy player in a crowded art market for 2020. Solid sales at the launch and an adventurous spirit mark the gallery out as a place to watch in the months ahead.

Daniel Benjamin Gallery

19 Dec-15 Feb 2020

120 Kensington Park Road, London, w11 2PW

www.db-gallery.com

Liz West’s Website

Jemma Appleby’s Website

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle