Weaving words together, you’ll speak most happily

When skilled juxtaposition renews a common word

– Horace, Ars Poetica.

Skilled juxtaposition, whether in words or imagery, is the remit of the artist. Presenting the known in unknown ways, teasing out the unfamiliar from the familiar. For Malcolm Leyland, an earlier career in commercial photography lacked the opportunity to apply those visual twists and turns to subject matter.

Eschewing that commercial direction gives Leyland the freedom to take his work into more expressive areas, using composite photography to address that conundrum most intriguing to visual artists throughout time – the rendering of three dimensional reality and human perception onto two-dimensional images.

‘…part of my curiosity/investigation is to look beyond the conventional ‘single viewpoint / stolen moment’ framework as typically defined by the camera. For many, the ‘single viewpoint / stolen moment’ is the end of the road in creative terms.

For me, it is just the beginning.’

Malcolm Leyland talks to Trebuchet’s Kailas Elmer

Trebuchet: Tell me something about your background

I grew up in the Wirrall area, outside of Liverpool and moved to Warrington at around ten years of age. I had an interest in photography early on due to it being my father’s hobby.

As a child I was making pictures as much with the camera as I was with drawing and painting. We had a darkroom at home and my father taught me everything I had to know.

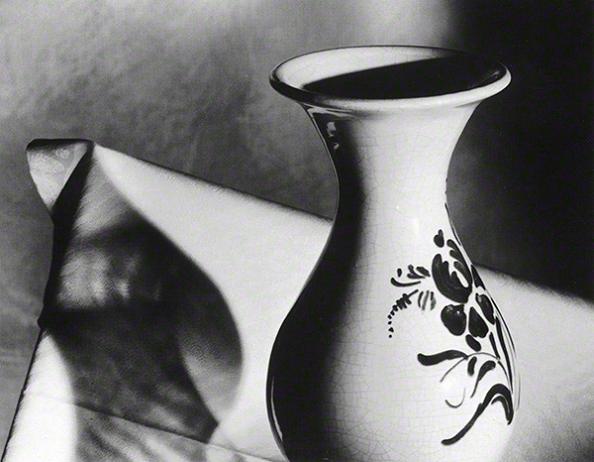

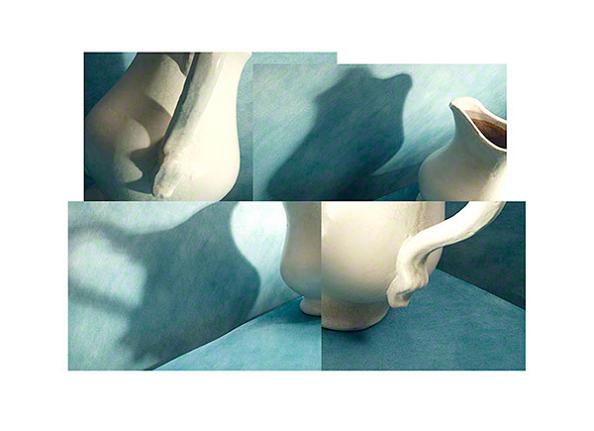

Malcolm Leyland, ‘Vase and Table’.

By the time I went to art school I had already experimented enough to make the medium as natural to me as I could, but actually my primary focus was still painting and that was what got me into art school.

The foundation courses at that time were great, you did everything: photography, pottery, print making, drawing and you had a chance to really get into each activity and try it all out. This allowed you to discover which medium best enabled you express yourself.

[quote]taking multiple views of a

scene I am attempting to

recreate something more real

than an isolated image, which

is not how we experience things.[/quote]

I was always inspired by painting but again I gravitated towards photography and film making. This created a tension, I wanted to be as expressive as I could with paint but preferred to use the static medium of photography. So, at this early stage I told myself that I should find a way to make photography, as a medium, as expressive as paint! I wanted to do something different with photography.

For me photography was always a fine art medium but back then it wasn’t as established as such. This added to the dilemma for me going forward.

Trebuchet: What sort of paintings where you doing at art school?

At the time I was very influenced by Cubism, the way that the viewer was seeing more than a single moment, or a single perspective. I liked the way these paintings were constructed, there’s a sense of composition that really resonated with me, still does. I was looking at the work of Picasso, Braque, Gris, Giorgio Morandi, Paul Klee. Also, early influencers of photography: Man Ray, Arnold Newman and Guy Bourdin.

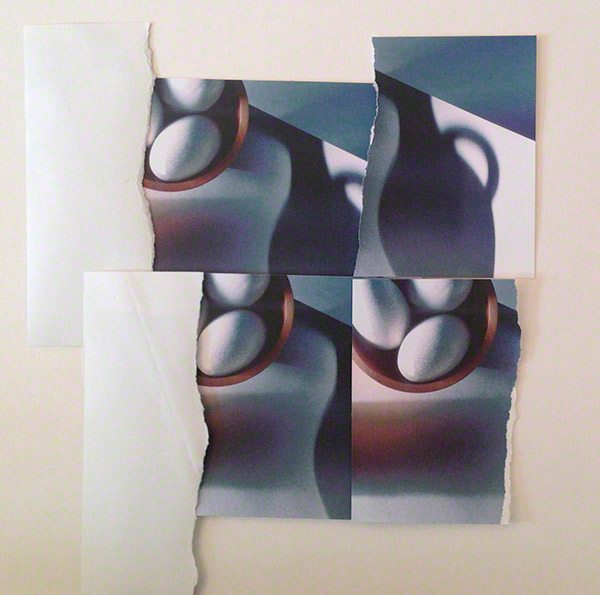

Malcolm Leyland, ‘Eggs in a Bowl with Vase’

Trebuchet: When did the full transition into photography happen and why did you chose a commercial art path?

I was investigating all of this at art school and was nearing the end of the course when I started to get into photography primarily. I was very interested in working in the studio, doing still life work with photos, and that sort of led into commercial photography.

At the time photography was really in a commercial heyday. It was the era of magazines and advertising was ruling the culture in such a monolithic way, it was very attractive to me. Also the work that I was doing at art school with photography felt part of the times, so that was pretty much all the encouragement I needed.

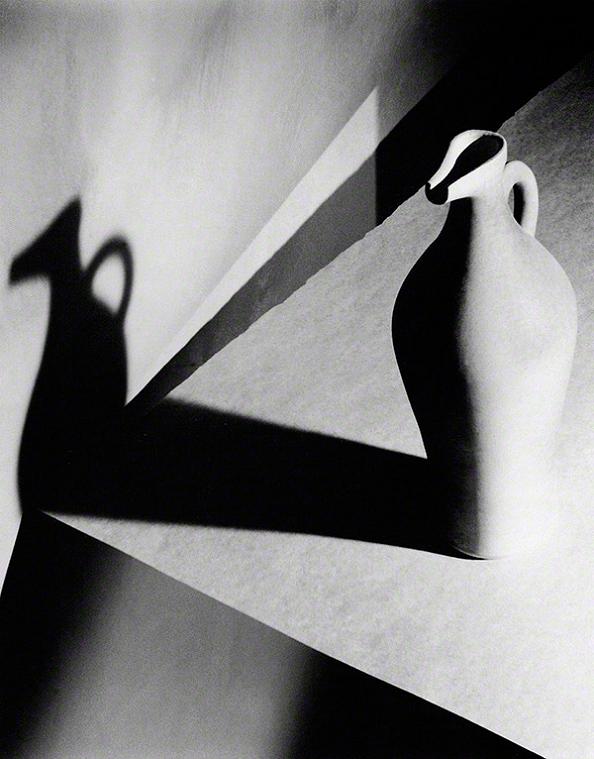

Malcolm Leyland, ‘Vase with Shadow’

Trebuchet: Was it an easy period to establish your reputation?

After art school I worked as an assistant before going into photography for myself in my mid-twenties. It was slow progress taking your portfolio around London.

I remember you had to have the right type of images within your portfolio for a particular commission. You just wouldn’t get hired for a photo shoot for a beer campaign, for example, if you hadn’t photographed beer. Moving forward was very tedious.

Other times you’d get a commission because the art director could see your abilities and wanted to use the qualities you could add to his ideas. This meant you could influence the imagery, it also meant the agency had put their faith in your abilities – it was a creative period for advertising.

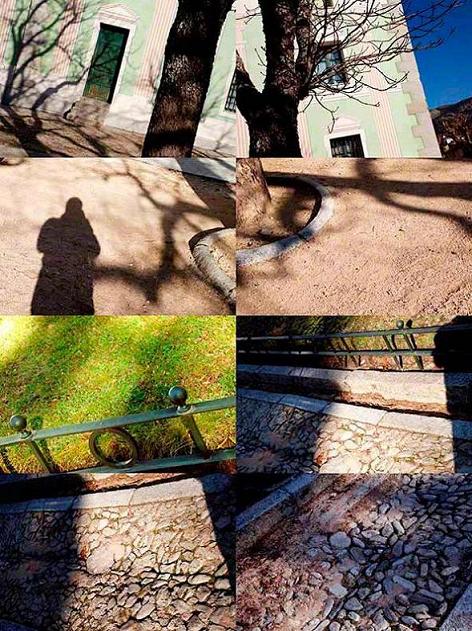

Malcolm Leyland, ‘The garden at bar 163’

It was all very subjective but also quite energising because it was expected that your portfolio contained some creative shots as well as the commercial stuff you’d done, which in my case was never that far away from what I was doing artistically anyway.

I was always looking for the textures of things and trying to play with the sense of perspective and finding the unique qualities of the subject, that elusive element captured with light and composition. My commercial work was eventually so influenced by the artistic qualities that I eventually derived a style, which you could say became a commercial signature.

Trebuchet: So, now you’re not working commercially?

No, and I must say its a great sense of relief, of freedom, not to be required to produce images under the influence of a commercial need. All decisions are mine and made for my own reasons, while the purpose of the imagery is entirely driven by my own visual demands. The raison d’etre is entirely my own.

Having said that, the long period of intense image making has forged a discipline of intense looking, observing, quick decision making, and a very high expectation of quality, both visual and in production. I know all the rules – so now I can break them!

Trebuchet: Tell me something about that.

When you take a photo you are involved in the capturing of a moment. On one level that is the most important point of photography when you are capturing what you see in the camera. It’s a momentary decision that defines the shot. So obviously it’s often considered the most creative point the process.

The discipline I learnt in the advertising studio is the slowly applied consideration which over a day or two would build up that perfect image (the perfect image is always required in advertising).

Trebuchet: Is there a theme to your work?

Currently the themes are Objects and Places. These are differentiated only by technique, I guess. Each are a study of the subject approached in the same way, but objects are a macro inspection of of something and based in the studio, while places are an attempt to capture the atmosphere of being there.

Malcolm Leyland, ‘Table’

Trebuchet: Tell me about the process you’ve been working on.

Well, as you can see, the resulting images are made up of several different shots that are put together in what I think is a more revealing and dynamic way than a single shot of a static object or place. As I’ve said before, the act of taking the photo is usually the creative act in photography (not counting setting up a shot, dressing a scene etc., which in essence still leads up to that moment of taking the shot), but what I’m doing is taking several photos of the subject (which may be a scene rather than a thing) to capture the moment which is a series of instances, rather than a single static shot. I’m extending the creative moment.

As I move around the scene taking photos I’m making several decisions each time, and capturing them. Then in the studio I am reassembling them to make a relatively cohesive object but reordering the time sequence within the scene, shot by shot, as a painter may do. The final picture may or may not resemble the scene, it becomes a reconstruction of the scene or object.

When I put the shots together I look for visual connections it terms of line or idea but which inevitably results in a new dynamic.

Trebuchet: when you’re taking these shots do you try and capture the same light, or use a specific f-stop, or something to make the raw material even?

No. Nothing like that at all. I try and capture the natural shapes, light and motion in the best way for each particular perspective. You see, all these perspectives, though connected, are their own in some way. To try and make them average by imposing a rule isn’t what they’re about.

But on another level I’ve been taking pictures all my life so the process of taking pictures is quite direct for me. Commercially you have to take pictures in a certain way that all the details are present, so I adhere to that to some extent, willingly or not (laughs).

Trebuchet: Is there a difference in approach between your studio work and the pieces that are based on outside scenes or subjects?

Of course. There is total control in terms of what you can achieve in the studio. Light. Objects. Everything. Whereas outside you are at the mercy of the moment. Sometimes you’ll see something that will grab you in the right way then you have to go with it.

In the studio you are in the room with your vision, or ideas, or however you imagine the shots will emerge, or how a particular tone of light will work off a certain surface or number of surfaces etc. But outside it’s all a matter of being in the right place at the right time, but also finding a subject that contains more than could be contained in a single perspective. Which I suppose is a bad way of saying: somewhere that ‘interests’ me.

Trebuchet: Tell me about the shots from Spain.

I found the location when I was on holiday with my family one Christmas. They were off doing something and I was just wandering around pretty much. I noticed that the light was coming from a very low angle, it was winter in Spain and the light was intense, rather like a spot light in a studio. It was creating all sorts of very interesting shapes and contrasts from buildings, trees, and street furniture.

I went back there the next day to shoot ‘The White House in la Granya’, and La Granya.

Malcolm Leyland, ‘The White House in la Granya’

Trebuchet: Looking at your work I can see that some pieces have a predominance of a certain colour. Do you use colour in a symbolic way?

Interesting thought but no, although the introduction of a colour can indicate or induce a mood, but I leave that for the viewer’s participation. The single colour does however effect a more concentrated view on the dynamic of the picture, the forms of the objects and shadows.

Malcolm Leyland, ‘Pool’

Trebuchet: Would you say that in that respect light could be seen as another theme of your work, emotive and otherwise?

Yes indeed. Light, either natural or studio, is the essence of making images with photography. Controlling light is a discipline that must be mastered. Then looking at light to form shadow gives that extra level of control the resulting shapes become part of the dynamic of the picture.

Trebuchet. You’re emphasising the position of the viewer/photographer in the photos by taking photos at unusual angles, etc. Are those choices guided by a philosophy or an aesthetic?

Oh for sure there is a philosophy at work, but aesthetics deliver the experience. When you enter a place your eyes move from one object to another. There is always a lot going on in any place you may visit. You are constantly moving around, and your position related to your environment is constantly changing or adjusting.

There is so much visual information that we cannot and do not capture it by a single static image. We may try to remember a single vista but that vision is made up of many views.

Malcolm Leyland, ‘White Vase on Blue’

By taking multiple views of a scene I am attempting to recreate something more real than an isolated image, which is not how we experience things. Then I reproduce them in a two-dimensional linear way and the aesthetic gives the viewer a reconstructed experience of my experience as I walked into that place.

Hockney mentions time when applied to productive picture making, and that quality being missing from photography. I found that really interesting and the way I work removes the necessity of capturing that single moment so synonymous to the medium. Mine is a very considered approach and the opportunity to change, to add, to remove is always present which, for me, helps to make the medium of photography extendable and therefore for me much more creative.

Trebuchet: Is there an end point to this sort of creation, something that you are reaching for?

That is impossible to say; from a personal perspective, each piece is finished within itself, and I learn from it in the sense that I’ve carefully explored a certain way of seeing as it relates to the subject or subjects within the piece, but that in a sense alters how I see my previous work, the other pieces in development and even the inspiration I get when I’m out photographing.

So in that sense the combinations of photos in my work are reconfiguring the creative world around me which interests me as much as it constantly changes what I’d like to do, which I think is how it should be.

Editor, founder, fan.