Over the past 50 years, Marina Abramović has pioneered performance art, testing the limits of her physical and mental endurance while prompting intense emotional reactions from audiences across the globe.

Following the publication of our latest issue Materials II, Millie Walton shares the transcript of her conversation with the artist which informed her essay Decoding the Body as Language: Marina Abramović.

How do you think your relationship to your body, and to your body as an artistic material has changed over the years?

In the beginning, I was much more interested in the physical aspects: in the limits of the body. When I was very young I went to see the most difficult operation that can be done to a human, which was the replacement of the hip and spine. The operation lasted between three to five hours. They use saw machines, screws and metal, to cut the body into pieces and then put it back together again. This was pretty fascinating to me and so I decided I wanted to experiment with pushing the body to its limits, exploring how I deal with pain. I had done all this research and lots of performances in this direction and I became a master of suffering, of transferring the pain into something else. I overcame the fear of pain.

Then, in the second period of my life, I became more interested in the mental limits of the body and eventually, came to the point where the mental and physical body unite to create balance. Of course, we have another aspect now: the older body. What happens when the body ages? What happens when you wake up in the morning and you have pain everywhere? You have to work within your own limits and do whatever is possible. I don’t want to ever stop performing. I think I will perform dying.

You have an intimate relationship with your body, but during performance, it’s sometimes lent to the audience as a kind of object – how do you negotiate that shift?

That’s a very good question. You have your intimate body and the public body. It’s very clear to me that the public body is different from my own body. It’s a very strange contradiction, but I am shy to undress in front of my friends in an intimate situation and yet, I don’t have any problem being totally naked in front of audiences that I don’t know at all. There is a transition from the private body to the public body. The public body is a symbol for the body, any body, so I don’t care if I look fat or if my breasts have a shape I don’t like.

Is there a process that you go through to access the public body?

In the early days, I was so afraid and even now, I still get the same uneasy feeling in my stomach. Before a performance, you’ll find me sitting in the bathroom trying to pee, but not being able to and then the moment, I stand in front of the audience everything disappears. I’m used to this fear and if I don’t have it, I’ll be panicking. It’s part of the process: you feel the tension and then you enter into the public body and everything is okay.

Can you perform without an audience?

If you ask different performance artists, you’ll get different answers. My answer is really personal: I will never do a performance without the public. I don’t see a reason for doing so because my performance is about an exchange with the audience, it’s about creating an energy dialogue. The performer and audience create the work together, they depend on each other. That marriage is very necessary for my performance to be successful, but there are different types of performance. There is performance which is just for video, for the camera, there is performance for photographs and now, there’s also performance for making virtual reality or augmented reality experiences, but for me, old school performance is about me and the audience sharing space. I am there for the audience.

Are you interested in exploring augmented or mixed realities?

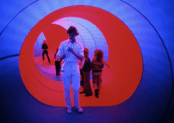

Of course! I’m interested because I’m always thinking about immortality, and the future. Until now, documentation of performance has just been video and photography. Photography is definitely not interesting because it doesn’t include sound or movement and video is usually just one point of view, but with mixed reality, you have thirty six video cameras which create a 360 degree image. It’s built from particles of energy. When I began experimenting with the technology and saw that image for the first time, it really touched the idea of immortality. You can put glasses and I appear in your living room. The one big problem is that it’s so inaccessible and it’s incredibly expensive to make. I recently made a mixed-reality work called The Life, which was a very expensive project, and it took one and half years to make it, but I want to make more in future.

Some of your pieces seem to entail passivity, such as Rhythm 0 (1947) and in a different way, The Artist is Present MoMA (2010). Is some level of disembodiment required for such performances?

I was very young, when I performed Rhythm 0, only about 23, and pretty crazy. I laid out a pistol and a bullet, and wrote in a statement that I would take all responsibility if anyone used the pistol and killed me. That performance was really coloured by my anger at the public at that time because performance art was being ridiculed. I wanted to see what would happen if I put 72 objects onto a table, and gave the public the opportunity to do whatever they wanted to me in a period of six hours. I wanted to see how far they would go without me doing anything. I had been criticised as a sadist and masochist so I decided to take a totally passive role, which required me to be present and very stoic. If they changed my body position, I stayed in that same position. I became a puppet for the public. At the end of the performance, I realised that the public can kill you. I was lucky I survived.

Twenty five or so years later, I created The Artist is Present and I gave very strict instructions to the public: you can sit in front of me for as long as you want and engage in the gaze, nothing else. With Rhythm Zero, the reaction I got from the public was very violent and ugly – they cut my skin, drank my blood and stuck thorns into my body. With The Artist is Present, the reaction of the public was very emotional. They cried, and really got in touch with their deeper self. In that performance, I isolated the public, one on one, but still within the group because anyone who sat in front of me was photographed, and filmed, and watched by me and watched by the wider audience, and there was no where to go expect deeper into themselves and when that happened, it was very emotional. I could have done The Artist is Present when I was young. I didn’t have the experience, the willpower, concentration or wisdom.

How does your work explore ideas around exposure and vulnerability particularly in relation to gender?

I make so many statements concerning women and feminism, in which I say, “I am female but I am an artist.” I don’t admit that artists have gender because I don’t care who’s making the art, the only thing that’s important to me is good art and bad art. Personally, I distinguish three Marinas, three different types of person who live harmoniously within me. At the beginning, I didn’t want to admit to three, I only wanted to there to be one, the one who’s the warrior, who goes through the walls and doesn’t care about anyone, but there’s also the spiritual Marina, and the bullshit Marina who loves chocolate, TV, movies and bad jokes, and is a very emotional and vulnerable person. From the moment I started showing all three of those Marinas to the public, it was a dream. I was so liberated and happy, I didn’t need to hide anything. When you only try to show what you think is the best part of yourself and hide the rest, the public finds those hidden parts and trashes you in the press. In my case, that’s not so easy to do because I show everything.

Was there a particular moment when you made the decision to be more open?

Yes. I had just finished walking the Great Wall of China with Ulay to say goodbye after our relationship had ended, two and a half thousand kilometres, each of us walking in opposite directions, and I remember writing in my diary that I felt ugly, fat and unwanted. I was 40 years old and I felt so sad, but I said to myself I want to have a life full of laughter. So, I went to shop in Paris and I bought myself designer clothes, I went to a hairdresser, I got a pedicure and manicure. In those days, having lipstick and nail polish meant that you were a bad artist because people assumed you wanted to seduce curators into making a show with you. As an artist, you were expected to look kind of rough, but I did the opposite: I made myself look and feel beautiful, and realised there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s when I started to show all parts of myself to the public.

Audiences often have very intense emotional responses to your performances. Why do you think that is?

There’s a friend of mine, an American critic, who says, “I hate your work because it always makes me cry.” People want to have an intellectual response to art, especially the British, but when I performed 512 Hours at the Serpentine Galleries in 2014, lots of people cried. I think before you understand the concept of my work, you have an emotional reaction to it. To me, that’s the right kind of response to art. It has to move you in a certain way. If someone asks me, “What’s a good piece of art?” this is how I explain it: if you go to a museum and you have strange sensation someone is behind you and you turn, and there’s this work of art, its energy is drawing you to it and that means it’s good. With performance, everything is memory and sensations that you have. Good performance continues to live through narrative, the stories that people tell about the experience. Performance is very fragile and because of that, it’s one of the most difficult forms of art there is. I’ve spent all my life trying to bring performance into the mainstream category.

Why do you think it took so long for performance art to be accepted?

Because of its structure: performance art is immaterial, and time-based. Also, there are a lot of bad performances.

In your manifesto, you write that “the deeper the artist looks inside himself, the more universal he becomes.” Can you explain what you mean by that?

I was teaching for many years and I would say to my students, “It’s always important to follow yourself. Don’t follow the fashion. Don’t do things you don’t know anything about. Don’t follow other artists.” If I get asked which artists have inspired me, I don’t have an answer because I think if I were inspired by another artist, it would be a kind of secondhand source. You have to go to the main source, which is first yourself and then, nature. The deeper you go into yourself, the more original you become. You have to be authentic and love what you are doing. People often ask me how to become an artist, and I say, “You can’t become, you are an artist or you’re not.” You have to be born with an urge to create.

There’s also a section on the erotic. Why is eroticism important in the making of art?

I talk about eroticism as a very important part of human life. The primary energy we have is energy for reproduction. The more erotic energy you have, the more you have to give because it can be translated into sexual energy, but it can also become creative and destructive energy. The more energy you have, the more potential you have: the passion to love and to suffer. People are often afraid to fall in love because they are afraid of suffering, but I don’t think you can have one without the other.

What made you decide to open up your archives and give younger generations of artists the chance to re-perform your works?

The decision came about in 2003. I was so fed up with the disrespectful approach to performance art. Fashion designers, filmmakers and magazines were taking ideas from performance art and stealing them. Younger artists were literally copying older artists’ material and critics were praising them for their brilliant new ideas. I felt I had to do something about it so I made a work called Seven Easy Pieces which I performed at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2005. I chose five original pieces of performance art that really impressed me plus two of my own, and asked for permission either from the artists themselves or from their foundations to re-perform them and I paid for the right to do so. I wanted it to be an exemplar. After that, I opened my performances up to be re-performed by younger artists. You have to audition, and we decide whether they can do it physically and mentally. I don’t give permission for any of my works which would put the artist in danger such as Rhythm 0 and no one ever asks about The Artist is Present because it’s so long.

Does it matter to closely they stick to the original performance?

I want it to be as close to original as possible, but if the artist also wants to include ideas of their own, they are totally free to do so.

What’s it like for you to see other artists performing your work?

Difficult. I get really emotional and generally avoid it if I can. The most emotional experience, for me, was recently when I saw a female artist performing the House with the Ocean View which is twelve days without food, only water. When I went, it was seven days into the performance and I know how hard that piece is. My life is continuing without me. There’s a feeling of responsibility, but also release.

This interview was carried out in April 2021.

Marina Abramović’s solo exhibition “Seven Deaths” will run from 14 September to 30 October 2021 at Lisson Gallery, 67 Lisson Street & 22 Cork Street. For more information, visit: lissongallery.com

Featured image: Marina Abramović, 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, 2019. Photo by Marco Anelli. Courtesy of the Marina Abramovic Archives and Lisson Gallery

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.