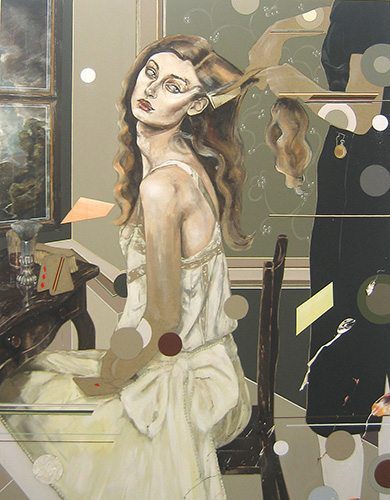

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]ver the course of several years Martha Parsey has grown from strength to maturity without her paintings losing their edge or their interest.

From her Candlestar show in 2011 to her well-received, If 6 was 9, at the Eleven gallery in January 2013 Parsey’s work has gone from strength to strength and complexity to complexity.

When looking at the most recent exhibition:

“Parsey ‘s palette still has a strong sepia tonality and again dials into the mythic feminine figure, however there is a technical development in these works that we haven’t seen before.”

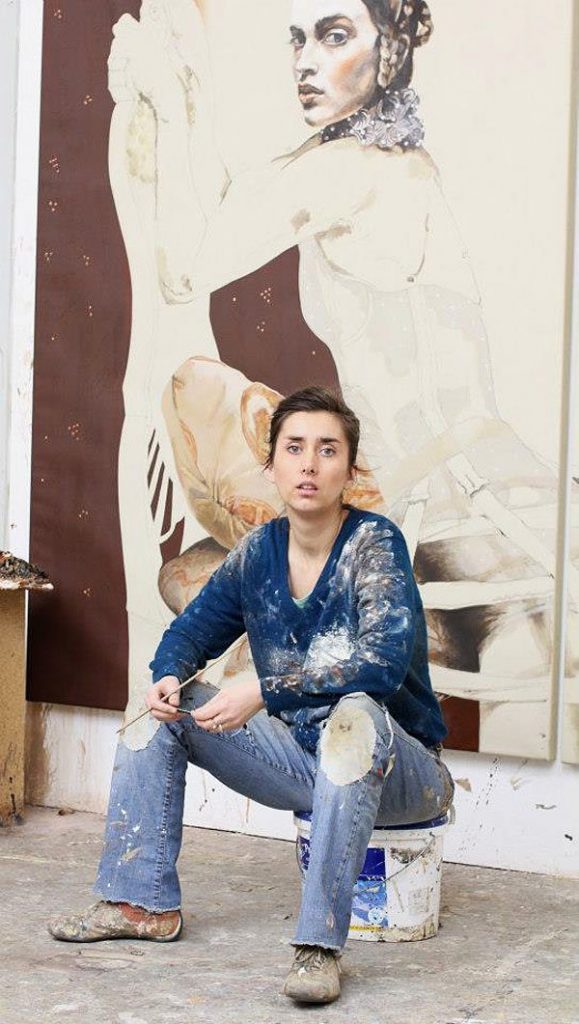

We were lead to more intriguing questions than was usual for a London private view, and so Trebuchet finally met up with Parsey to talk through how she sees her art and to describe some of the techniques she uses.

Trebuchet Magazine : Who are the subjects of your paintings?

Trebuchet Magazine : Who are the subjects of your paintings?

Martha Parsey : A whole variety of people, but always, primarily, people. Apart from in my very last series where I experimented with still lifes, the figure is always the central focus of my work, a figure in a particular setting or situation.

Where do you draw these characters from?

I’ll have an idea and then source photos or photos will generate an idea in themselves. I’ll normally use a whole array of photographs and then amalgamate them in my head and through drawing.

I don’t do any preliminary sketches but draw straight onto the canvas, which is a way of piecing them together and working out the composition. I don’t use a projector – I know a lot of people do. I think it’s cheating – because the actual process of drawing, eye-to-hand coordination and how your brain distorts and interferes with that, is what makes drawing so interesting.

When you’re choosing these figures (can we call them characters?) do they embody a message you’re trying to convey (as archetypes for instance) or is it that they have a position in the paintings that allows the composition to make sense, an emotional abstraction rather than a specific character?

I’ll see figures, characters if you like, and I know that put together in a scene they will set each other off. There will be a natural tension, dissonance or correspondence between them that has a dramatic element, and like a fuse it is somehow charged. David Sylvester, who was a good friend of mine, described it as an ‘electric charge, a bitter taste, a threat of erotic danger’.

You have a strong sense of geometry in your work, do you actively try and skew perspective and what do you make of this tool?

You call it skew perspective, I’d say ‘screw perspective’. As Hockney quite rightly keeps banging on about, a lot of our preconceptions about perspective are actually quite wrong and quite undeveloped.

I’m experimenting at the moment with a three-dimensional canvas, so that the picture actually comes out at you while still being a two-dimensional surface. I like the way that messes with our quite artificial notions of realism so that you’re not quite sure at first exactly what it is you’re looking at.

Can you explain more about Hockney’s ideas on where western audiences are with perspective?

Sure, but he hasn’t made a secret out of it, he’s written and talked quite a lot about it. He talks about shifting viewpoints which isn’t a modern idea at all, the ancient Chinese were doing it. It’s a way of creating spatial relationships within a painting, and of shifting the view so that we can see a variety of viewpoints at the same time, a perfectly feasible idea that accepts plurality within the picture-making which western audiences were still struggling with when Picasso and Braque approached this in the twentieth century.

The ancient Egyptians were already seeing the surface as a space with divided levels, not as a replication of reality, it is very sophisticated picture making, as are the cave paintings of Lascaux.

Perspective, as we like to call it, as it was created in the Italian Renaissance, (probably with the emergence of the first optical lenses, although Plato had already written about the problems of perspective in classical Greece calling it ‘a weakness of the human mind’) is understood by western audiences as a sign of the artist mastering realism by creating an illusion of spatial/pictorial depth.

[quote][Perspective is] an illustrational device, and a pretty cheap one at that[/quote]

What it actually amounts to is a limitation of the painting to the single viewpoint and breaks the picture down to an over- awareness of the position of the artist. In a rather egocentric and self-conscious way it represents the whole world in relation to oneself. It’s born of the principles of photography borrowed into painting as an illustrational device, and a pretty cheap one at that. The world doesn’t exist according to our view or perspective and it’s a fool’s game because it restricts painting to the restrictions of the camera which painting is actually entirely free from.

You asked about geometry, which is related to this, perhaps it is my little flirt with some of the artists I admire, like Mondrian or Maholy-Nagy, we’ll never get back to quite how ground-breaking they were. I like the crispness, it’s very seductive, but I have been moving away from it, as there isn’t such a thing as a straight line, and it can be very limiting.

What do you mean when you say there ‘ isn’t such a thing as a straight line’? It’s a wonderful phrase but how does that inform your painting?

Show me a straight line. There are a lot of things that look straight that aren’t The horizon is not straight. It curves with the curvature of the earth. We know from quantum physics that light does not travel in straight lines. It’s a comforting fallacy, a way of trying to make sense of the world, order, measure and contain it. Again – gain perspective.

[quote]in painting, constructs don’t serve us very well[/quote]

There is no direct path from A to B, there isn’t even an A and B. So, much as I love geometry and maths, it is a construct, and in painting, constructs don’t serve us very well. Painting’s very adept at exposing them, betraying the deceit, when we over-indulge in devices and conceits.

VERNISSAGE | Martha Parsey “Out on a Limb”

The painting seems very conscious of the viewer, the figures engage as though they are performing for an audience?

Well, they are. You can’t paint a picture nowadays without there being an awareness within the picture that this is of course a painting. To ignore that is dismissing at least the last 150 years of art history and the way in which photography has fundamentally changed our way of looking at things.

The camera has punctuated, penetrated, assaulted even, the distance between the viewer and the image by the proximity of the camera and the cinema in close-up. Not only by bringing the world and ourselves closer to us for scrutiny, and breaking down the division between the audience and the image, but by our identification with the figures, projecting ourselves into the image before us, we become participants in a discourse and therefore co-productive of the pictures’ meaning.

I want that to be visible, the figures should look like they are aware they are being looked at. They mirror the gaze of the viewer, so there is rarely a picture of someone unawares engaged in an activity but mostly looking back at us and engaging us in their presence. Like Godard said ‘looking at ourselves in the mirror of other people’.

[quote]this is a painting made out of paint on canvas, it’s not imitating life[/quote]

Also, the application of the paint should be making it clear that this is a painting made out of paint on canvas, it’s not imitating life. That’s why I like certain passages of very thick paint, many different forms of representation from figurative to graphic to abstract, even paint thrown on the canvas so we are made constantly aware, are constantly reminded, of what it is we’re looking at.

Quite so, and you reverse this in sections where you leave the canvas bare (though arguably not blank). How did that idea come to you?

I’m glad you bring it up and make that distinction. The bare canvas is a very important, and probably the least understood, part of my painting. Firstly, it reveals remnants of the initial drawing that I like to retain and to remain visible in the final painting. Like part of a skeleton, it’s good to see what the thing is actually made of. Also, by having some areas painted in great detail, and others left bare, not only does that intensify the effect of the painted areas, but gives the surface two layers, a kind of plus and minus with the canvas working as a neutral tone.

You know Manet’s ‘The Execution of Maximilian’? He did several versions but the one I’m referring to is the one that was cut up and sold off in parts after his death which Degas later bought and reassembled on a blank canvas. (Beautiful story for another time). The point being, that the re-assembled painting is not only marvellous, but is by far the superior of all the versions Manet did, precisely because it is partially not there – as much for the gaps between the action as the action itself.

You have to regard this as an action painting as the subject of it is the execution, but half of the scene is actually not visible, it takes place almost entirely in your head, and that’s why this painting (you can see it in the National Gallery) resonates beyond all the other paintings.

Why?

Because it leaves so much to the imagination. But the mind needs space in order for that to work and when there’s too much being presented to you, you switch off. That’s why it’s so important to strip things down- a case of ‘less is more’ . Look at Rothko – two colours and a fuzzy edge – and it’s a whole feast of sensation. Paul Valéry said it years ago ‘what modern man wants is the sensation without the boredom of it’s conveyance’, so if people are surprised that areas of my paintings are not painted, it’s not because I can’t be bothered to finish it.

Quite the contrary, it’s actually a fine balancing act, because if you paint too much it loses its resonance and the whole thing becomes fussy and tedious flower-arranging.

Also, the canvas has a tone and structure of it’s own which is unique, it’s a little like skin in that it is indelible.

I paint on the untreated side so that whatever I paint remains, that means really everything. I can’t take anything away without ruining the surface of the canvas – so there is no cheating, no steps back. What I paint is what you see, I have to get it absolutely right first time. There’s a constant tension or risk, because there’s no second take, no dress rehearsal.

Tell me the processes that gave life to:

If 6 was 9

I was starting to think about moving away from the figure. It was something I’d started in the vacant chairs in the 12 metre painting ‘Chasing the Dragon’. I’d noticed that a figure’s absence could be as compelling as the figure itself, character told through the remnants of a person, what’s left behind, a person’s presence beyond the periphery of their physical being. I was fascinated by this woman’s face, but I wanted to make that equal in importance to the flowers beside her, that they would also resemble her half wilting/ half vivid but very very colourful presence, so that objects in the pictures are as much a part of the composite of character as the figure itself.

The Second Marriage

I was looking a lot at David Hockney’s paintings of the early 1970s of homosexual couples which are incredibly attractive paintings. He’s very free with colour. The title was taken from one of his earlier paintings- it’s such a suggestive title I thought. I guess Hockney’s couples are more about the setting and surroundings than the actual figures, like in his pictures of Celia Birtwell, she’s more a decorative object than an actual woman. I wanted to change the hierarchy of the painting so that the couple become the background, obscured by the flowers in front of them.

Carnation/White Room

Also from a Hockney drawing I think, pen and ink. I photographed some flowers so they would have the same shadow effect as in his picture. I didn’t paint the flower itself, it’s completely blank, but instead the shadow it makes. I was trying in this series to move away from what you expect to be the focus of the painting, and painting either the mark something leaves or it’s reflection in objects or surfaces to multiply spatial relationships and viewpoints in a single painting.

The Maids

‘The Maids’ was a large work that I think in my head had been a long time in the making, because I’ve always been very interested in the work of Jean Genet. It’s obviously a fantastic play, but I was always interested in the thinking that accompanied it and it generated about the artificiality and deceit of performance and human interaction. There’s a brilliant introduction to it, I think by Jean-Paul Sartre.

And then when I saw this photo of a woman brushing the other woman’s hair, I thought, well there it is, there’s ‘The Maids’. So I painted it. The roles are very ambiguous in the play, between the mistress and the maid, and between the two sisters. They are always interchanging between submission and power, and a constant tension of who has the upper hand. Well, welcome to the world of women!

You have a signature palette with gold tones, beiges, and primary highlights. What informed these choices?

I did have, yes, but my palette is changing radically at the moment and the pictures have become what I term ‘mental’, which just means very very colourful.

In the pictures you’re referring to I was using neutral tones and balancing the painting, accentuating the focal points of the painting with strong colour; in those pictures that most definitely works. But now for no apparent reason that moderation has all gone to the wind.

Allowing all these very loud tones of colour to play together, almost deliberately and belligerantly trying to work against my own preconceptions and turn it all on it’s head, is very enlivening, exciting and liberating. So I’m feeling like I’ve just discovered the black keys on the piano, or the tones between the frets.

I don’t like music, I love music. Music is fundamental to me and to my painting. I couldn’t work without it, not only because it conjures up all sorts of sensations, inflections, nuances, but as I paint very large works and many at the same time, which can physically be quite demanding, it keeps me moving and dancing about. It also gets me in a kind of active energised relaxed state that is very conducive to painting.

There are also many parallels that are helpful, the rhythm is like the composition, like an armature on which to build, there’s the counterpoint of colour and form, and the areas that are heavily disciplined and structured juxtaposed with a kind of freestyle where you improvise and play.

I try to include all those elements into my work. I listen to all sorts of things and they set the tone: some music really helps me concentrate and focus on a higher level- I’ll listen to Brahms’ violin concerto which is mind-blowingly virtuosic – I play the violin so I know how accomplished the playing really is,- or Schubert‘s string quintet which is so brilliantly put together like a jazz ensemble. Or Corelli, Purcell, Bach, Stranvinsky, Vaughan Williams, Debussy, Satie- they are all absolutely amazingly awe-inspiring. I guess I’m hoping their brilliance might rub off on me!

If I’m building up layers then Steve Reich or Brian Eno, Phillip Glass, where ideas build gradually, and when I need to break that up, mess things up – that’s where Hendrix, or The Who or Leftfield, or whoever else (some beautifully outdated house/ambient/dance from my very distant clubbing days) helps me out. But to really improvise intelligently I’ll always go for the masters; John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, or my old favourite Charlie Mingus who I adore.

I really listen to all kinds of things and it doesn’t matter to me what it is. I like the freedom in music. I get totally lost within it – music is definitely my drug of choice.

Tell me about if 6 was 9, what does this song mean to you?

Well, for a start the title is what I stole and what I love. It’s a classic title. What does it mean to me personally?

It really would take too long to explain but I’m sure it means something different to everyone who hears it.

That’s what I love about music, it’s universal, it’s ambiguous and totally subjective just like paintings are. It’s something you feel as opposed to understand.

Many of your paintings reference famous songs. Tell me about this relationship?

Sometimes they’ll be songs I’ve been listening to whose ideas fit in with the ideas behind the painting but more often than not it’s the titles I’m after, because they’re catchy and suggestive, implicit without being explicit. I like a painting to have a title – it drives me up the wall when I go to an exhibition and someone’s work is ‘Untitled’. I don’t mean without a title. I can deal with that, although it does seem like a wasted opportunity. But titled ‘Untitled’. What is that? – some idiotic paradox- or practice of being downright awkward and obscure?

Even if we can’t pin our ideas completely down, it’s nice to have a few indications of what direction it might be going in to give people access, let them in, and I don’t think you lose any of your idea as an artist by being inclusive. Titles, especially things that may be familiar to people – song titles, idioms, things people know and associate something with, can help to invite people in rather than leaving them standing out in the bloody cold.

Will men appear in your paintings?

Why, are you offering? No, you’re far too pretty, I’d get distracted!

Funny though that you should ask, as I’m currently working on something in that vein which is very interesting, but I don’t want to say too much until it’s done.

I recently read a line that read ‘The woman is not really a person, but an entity inhabiting spaces, commanding the gaze of those that surround her‘ which made me think for a second and wonder if I’m in some sense using the woman as a motif or emblem of femininity to invite or entice the viewer into engaging with the picture and challenge us to challenge them.

I know that I when I’m making these figures which are predominantly female that I develop a strong relationship with them, I can get into role with them. I was an actress as a kid so I probably quite enjoy that aspect of it, investing them with facets of my own personality.

I think part of their power resides in the fact that I can embody them, so that they look out at us, so that I’m painting them from the inside looking out.

All Photos Courtesy of Martha Parsey.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle