[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]ass Observation: This is your Photo: both halves of the title of this new show at The Photographers’ Gallery conjure an image of an instagram-happy generation, inhabiting a web-focussed world wherein that tin of baked beans – that should speak of student debt – becomes infused with the talismanic glamour of a new language of ‘filters’ and ‘likes’.

It is easy in such a environment to become detached from our actual relationship with the world and to instead treat the documented, the shared, the approved – that which is aesthetically validated and transformed by that little eye pulsating in our pocket – as a depiction of the real.

[quote]Whereas our modern

army of instagrammers

set out to construct

a believed-in hyper-reality,

this collection opens

our eyes to the

world around us

rather than willing

it into more flattering

sepia hues[/quote]

We no longer look at objects but rather past to them to their re-representation. Our personal relationship becomes superfluous to the prospective public interpretation. ‘Comments’ litter our vision, we may as well have photographed the toast, though that may not have looked as artistic.

Photography in this sense is not capturing an intrinsic beauty; it is a tool for the manufacture of what we envisage to be beautiful- to be ‘likable’.

It is not so much that our lives are benile but, that they now reside in the shadow of our documentation of them – the more we photograph the more we need to do so, in order to illuminate and colour our routine. As we obsessively scrabble at transcribing every little detail, so that no stone goes unglazed, how can photography itself, with its aptitude for capturing those fleeting moments of unobserved, unadulterated humanity emerge unscathed?

In light of this perhaps This is your photo suggests something more illuminating since, had this been a gallery of selfies, a more apt hashtag may have been ‘This is Your Life’.

The Mass Observation Project was founded in 1937 by the left wing poet and journalist Charles Madge, the anthropologist Tom Harrison and the surrealist photographer and filmmaker Humphrey Jennings. It was conceived as a radical social experiment to document the lives of ordinary people in order to counteract what they felt to be an inaccurate representation set out by politicians and the media.

To this end a national panel of trained field workers, as well as amateur observers, were sent forth to report on different aspects of public behaviour. From the mundane to the metaphysical they kept diaries and filled in questionnaires on topics ranging from pub culture to the nature of happiness.

It was this written record that were primarily intended as the focus of the exhibition, rather than the photographs of Humphrey Spender – one of the undercover photographers enlisted alongside the reporters. His Bolton-based Worktown pictures which – exhibited here alongside those of artist Michael Wickham – make up the core of the first half of the chronologically arranged exhibition, were therefore documentary evidence and not in fact included at the time of the survey.

Details within the images were used as statistical data, such as the number of hats worn to a football game and the self behind the camera was self-consciously concealed in order to merge with the subjects so that they could be scientifically captured.

“We were called spies, pryers, mass-eavesdroppers, nosey parkers, peeping-toms, lopers, snoopers, envelope-steamers, keyhole artists, sex maniacs, sissies and society playboys.”

– Humphrey Spender

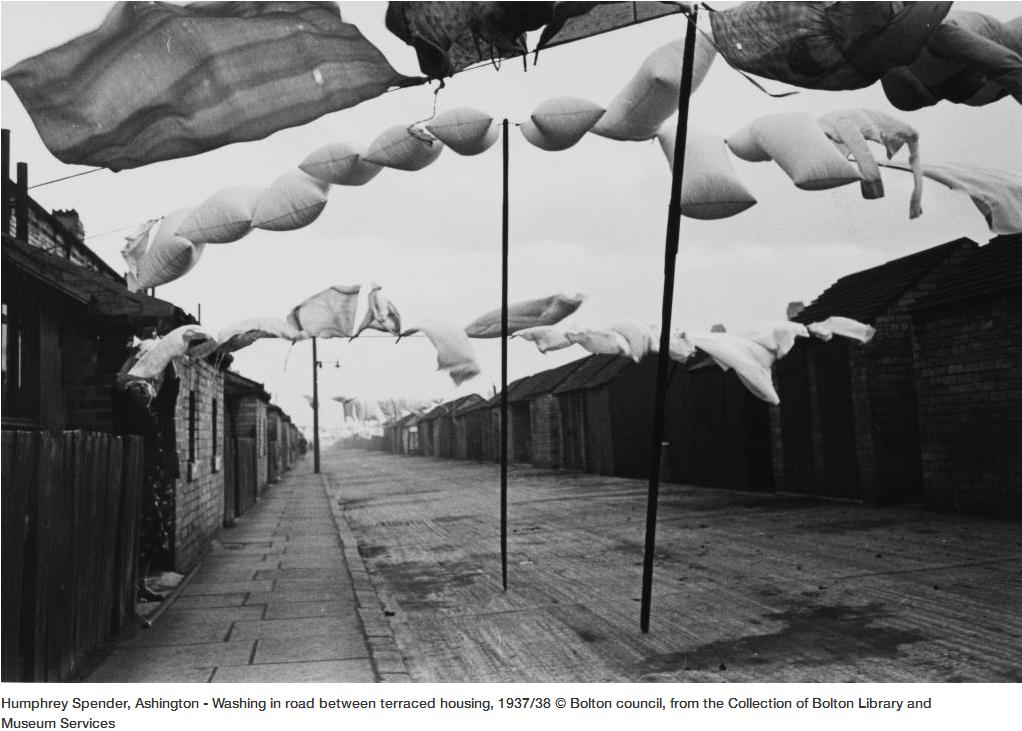

What is immediately striking however, is the profound artistry of the photographs. Spender’s camera is wielded with a candid humour and instinctive eye for capturing what Cartier Bresson refers to as ‘the moment’ of a photographic image.

Indeed, for someone who never quite conceded the importance of photography in documenting everyday life, there is much of Bresson’s theory of the photographer capturing the ‘places where the pulse beats more’1 in Spender’s images. A visual poetry is established by the depth of character conveyed in a look here, the anticipation of un-tucked handkerchief there, that is infused with a far more artistic aesthetic than pure documentary.

However, it is the intent for pure documentation that in fact lends the images a sincerity of vision. Whereas our modern army of instagrammers set out to construct a believed-in hyper-reality, this collection opens our eyes to the world around us rather than willing it into more flattering sepia hues. Indeed, the inclusion of the photograph ‘feigning fear’, in which the expression is deliberately staged, highlights the realism of the remainder of the works; their artistry arising from the relationship between raw subject matter and photographer.

We therefore encounter what the Japanese would term ‘wabi-sabi’- the intrinsic beauty of the everyday, encountered by embracing that which is undeclared, unassuming and un-materialistic. This beauty is conveyed in photography in its ability to capture those fleeting moments that make humanity so rich and complex.

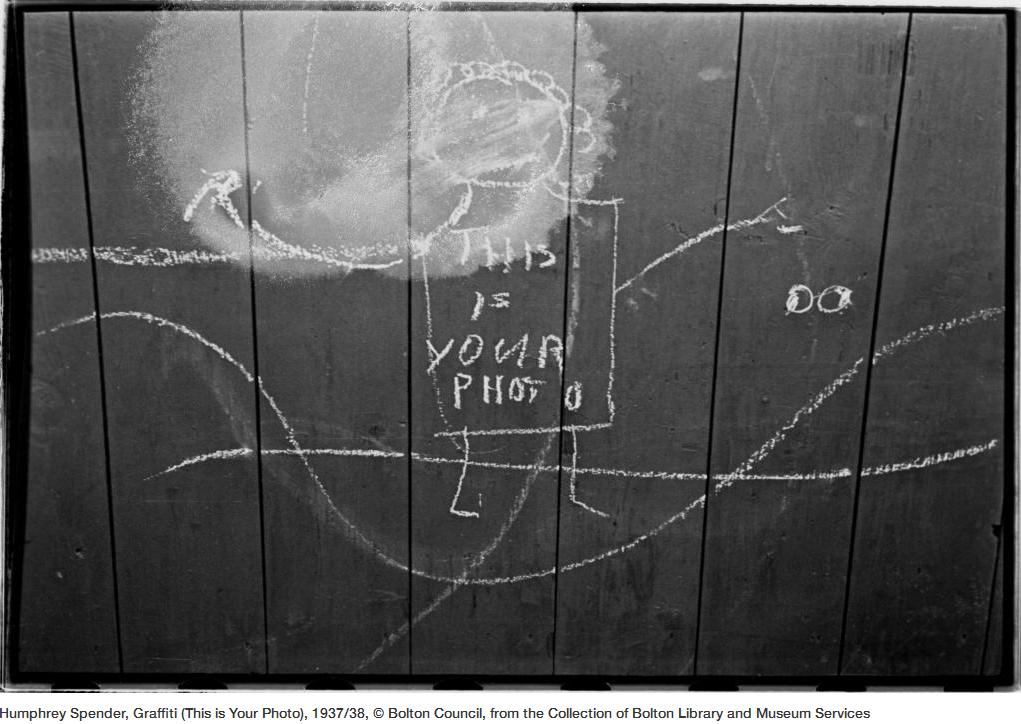

Workers leave a factory, markets bustle and Spender’s wry eye wrings out narratives from the seemingly mundane scenes. The tones may be black and white but the experiences are vivid and contemporary, brought to life by the photographers’ humour and talent for capturing tongue in cheek details. Images of (contextually) self referential street graffiti reading ‘This is your photo’, or the barber ‘Prof Fryer’ : the working man’s barber who could remove scruff, ringworm and dandruff, vie for space amidst the factory scenes.

The intentional inclusion of ‘artwork’ by collage artist John Trevelyn in the exhibition is relevant here. Trevelyn was instructed to work in situ much of the time, in order to document the responses of the public to contemporary art. The juxtaposition of his work with the photographs compounds the realisation that our reaction to art says as much about our cultural values as the portrait of desires and aspirations conveyed by the vitrines of Mass Observational ephemera on display.

Likewise, it is the narratives constructed by the aesthetics of the photographs which draw us into the archive and convey the true depth of the information on show. In this case therefore, it is our reaction to what is now deemed art that constructs the impression that the instigators of the project sought to convey.

The physicality of the photographer’s eye seems apt, rather than intrusive, infusing humanity back into a project whose intent, after all, was the creation of an anthropological portrait.

Returning to the extracts of observations, one could be mistaken for interpreting them as pieces of modernist fiction when they are read alongside the photographs. Their staccato rhythms and observational tone become akin to a Joycean stream of consciousness. It is this which saves them from the paranoia currently surrounding the medium of photography over its potential for unwanted surveillance.

Here, invasion of privacy is celebrated as a creative endeavour that will preserve those moments that can only be captured by those ‘peeping Toms’. Without these intrusions, such insights into British culture would not exist.

Following the end of the War, the organisation began to move away from social concerns towards commercial market research until its cessation in the mid-50s. English rural life is celebrated in the form of John Hinde’s heavily saturated colour photographs of Luscombe Village in Somerset, in order to promote foreign investment in Britain. The stark contrast with the black  and white images highlights the loss of realism, substantiating the implication that the roaming photographer’s ability to capture life is a far more informative method of documentation.

and white images highlights the loss of realism, substantiating the implication that the roaming photographer’s ability to capture life is a far more informative method of documentation.

We may be able to tell much from the whimsical depictions about the nation’s political climate, but the original ethos of representing the common man has been lost to construction and the same artifice of our social media-d selves: this is life but, as we choose for you to see it. Do you ‘like’ it?

There are echoes here of the paradoxes encountered in George Catlin’s depictions of Native Americans. Purporting to be in aid of conserving an anthropological portrait of a dying race, the egocentric concern of the painter to establish himself as a privileged expert results in an idealised depiction of what the public wanted to perceive, rather than what was truly encountered.

Catlin’s striving for acceptance as a painter is also evident in his portraits, immersing himself in another culture in order to gain a unique style which, though not distinctively skilled, is nonetheless ‘distinctive’ if only for its subject matter.

A similar disjunction is evident in the changing intent of Mass Observation, which makes us all the more thankful for the unpretentious anonymity of Spender’s photographs.

The project was re-launched in 1981 with a mission to recreate the ethos of its formative years. The second part of the exhibition presents photographs taken from questionnaires submitted by volunteers, alongside extensive written accounts that focus on the observer’s domestic life. The roaming eye is now directed inwards with a propensity at meticulously cataloguing possessions and property.

The endless handwritten documents have the whiff of a more egocentric consumerism, revealing portraits more of the people behind the documents than the information recorded.

It is this inherent failure that in fact testifies to the strengths of the exhibition. Such collections may seem unnecessary in our over-saturation of self-interested documentation era, however This Is Your Photo succeeds in justifying a re-focus on photography, empowered by an activist’s sense of mission.

The final invitation of the gallery to record your response to the images in the project This is Your Photo provides an opportunity to reclaim it as a medium and, in doing so, to reclaim some belief in the wabi-sabi of life.

Mass Observation: This is Your Photo runs until 29th September at the Photographer’s Gallery.

Inset photo: John Hinde, from Exmoor Village, 1947, © National Media Museum

Notes: 1Henri Cartier Bresson The Decisive Moment

[button link=”http://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/” newwindow=”yes”] The Photographers’ Gallery[/button]