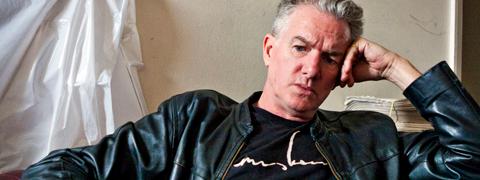

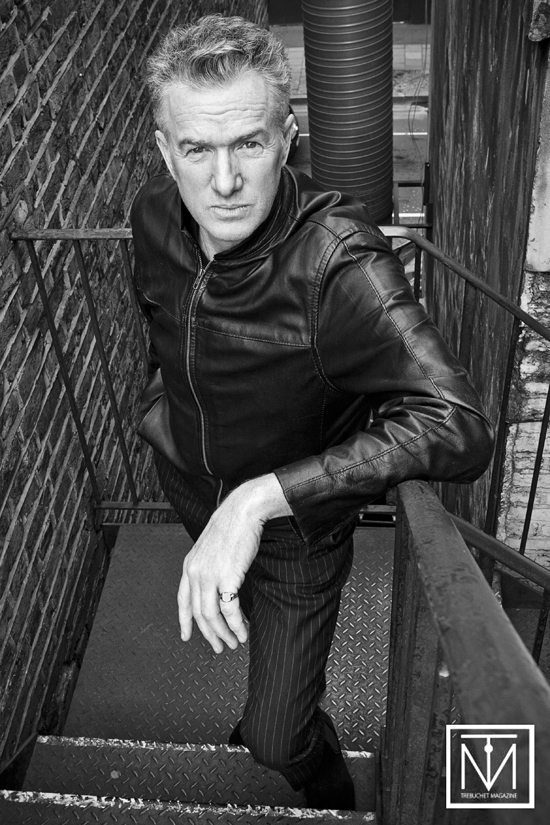

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]ick Harvey is best known as a founder member of seminal bands: The Birthday Party, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

In addition to collaborating with PJ Harvey, producing records, composing soundtracks and performing covers of Serge Gainsbourg songs, he has just released another solo album, FOUR (Acts of Love).

He spoke to Trebuchet’s Sarah Corbett before his recent gig at The Lexington, London.

Several of the songs on the new album have lyrics referring to the natural world and the elements – fire, sun, rain, earth, etc. Was that a conscious decision – is the natural world a significant influence in your writing?

Mick Harvey: Yeah, the first song on the album, ‘Praise the Earth’, is actually based on a hymn, but then I chose it. I suppose there’s something that I wanted to use, so it had some significance. Some of the earlier songs have aspects of that in them too.

I think when I start writing about what I’m interested in, it seems to come back to some of those things, like the relationship between man and nature and the universe.

If you’re going to be writing about anything inward looking and internalised, that’s fine because there’s a world in there too, but it’s really for me about how I’m communicating with the world, I suppose, and what’s out there, so I must find that interesting.

So does the geography of Australia play any part in that?

Mick Harvey: It’s hard to say how much of an influence that is but certainly you do experience the expanse of nature; it can seem quite huge there.

The sky is really huge and the distances are vast and you get out there and there’s nothing for hundreds of miles and you’re completely surrounded by ocean, everyone lives near the ocean and you just go to the ocean.

Has Australia influenced your work in any other ways?

Mick Harvey: It’s quite interesting there. Music and all the different areas of the arts are very much a mixture of American and European and all sorts of things, and it’s really a kind of hybridisation. What is most interesting, when things happen from Australian arts or musicians or writers or whatever, is when they have that strange mixture and create something different as well.

[quote]When you release

something you make

a public statement[/quote]

Especially with music, the really good Australian music, for me anyway, tends not to fall into any particular genres because the genres have all come from somewhere else so it’s a bit ridiculous aping a blues band or being a reggae band. Not that there’s many reggae bands. Well, a lot of the Aboriginal bands are reggae bands actually.

It seems really pointless to me because in fact all the influences that come in there are so varied and sort of disconnected from where they’re from anyway, but there’s a very strong European background with the culture there, so there’s a natural thing that it relates to that.

But the best bands there get this really amazing kind of strange blend so they end up with quite a unique sound.

So do you think Aboriginal culture has influenced other Australian music or is there a division there?

Mick Harvey: Well look, I think the Aborigines play reggae because it’s music from Jamaica about black people and freedom and the way they’ve kind of been empowered through their music, so I think it’s been inspired by that, that’s all.

But using that as music is a bit pointless really, it’s a bit of a waste of time in terms of doing something original artistically, you’re not going to get there being in a reggae band in the Northern Territory.

I feel that very much like that about the music I play, that there wouldn’t really be any point, and I wouldn’t enjoy it anyway, but there wouldn’t be any point being in some kind of genre, in a blues band.

You can probably see in some of the more interesting music that comes out from Australia that it isn’t really that definable, it isn’t really in a particular genre and that’s the result of the mixture of all the different cultures that have gone in there. People can find their own blend, if you like.

Would you ever consider dealing with Aboriginal land rights issues in your music?

Mick Harvey: No, no, not really. No, because I don’t know, I don’t really mix different political positioning with what I’m doing artistically, not like Midnight Oil or something.

There’s a famous group called Yothu Yindi that had a song, a big hit called ‘Treaty’, an Aboriginal band, it’s just about Aboriginal rights, I guess, about proper recognition and proper rights because it’s a pretty bad situation.

It’s not something that I would put into my music but it’s something I’m certainly alert to, which I must say a very, very large percentage of the population are not. They’re just living oblivious to it in the cities and stuff and don’t know what’s going on out there.

So do you think that the beach culture and the weather have a tendency to make people more escapist in Australia?

Mick Harvey: The climate tends to affect stuff like that; you see that in Europe too, with the Southern Europeans – the way they are compared to the Northern Europeans. It does create a different kind of mindset in some ways.

Although there is practically no Spanish culture in Australia (there hasn’t been because they’ve been a traditional enemy of Britain on the high seas for centuries so there’s very little Spanish influence in Australia) when I get to Spain as an Australian I feel completely at home, and that’s a very common experience. People just get to Spain and feel, ah I can chill out here.

But it’s really odd because it’s not like, oh it’s just it’s a beach and sunshine, it’s the way things are going on, there’s something very similar about the pace or something in the attitude that you just pick up on straight away. I know loads of people who’ve had the same feeling. It’s quite odd so it might be something in the climate. It’s hard to put your finger on it.

But the cultural thing is odd because of Australia being so remote and it still feels really remote when you’re there, it feels very geographically disconnected even though that’s no longer a reality. I travel back and forth a couple of times a year and with the internet and everything, everything’s just on tap. You’re not actually disconnected from the world at all, but there’s still just a physical sense that you are which is really pervasive, and because of the European basis to what’s happened there, there’s a tendency to feel that you’re culturally cut off.

I’ve realised since coming back and living in Europe that that’s my heritage. It took me ages to realise, I don’t know why, but after a while I thought, oh yeah I’m Australian and I’m European. It was really kind of strange, I never really thought about it that way. I think when I heard Papua New Guineans refer to Australians as Europeans, I was bit confronted with it. You know, I’d just never thought about it.

You’ve gone from an album about death to an album about love.

Mick Harvey: Well they came out of order actually, in a funny way. I started this one before and then chose to leave it. I chose to work on the other one first largely because I thought that Sketches From the Book of the Dead at the time was a more challenging project because I had to try to write the whole thing and I thought that was the kind of challenge I needed, the statement.

When you release something you make a public statement, basically you put it out there, so I felt that was the stronger statement to make artistically. Whether or not it was is debatable, but you make those choices based on where your gut feeling is.

[quote]I’m very much

a kind of Christian

Humanist in the

way I behave,

which is really

the way our

society’s structured

anyway[/quote]

At the time I felt that was the thing I should do so I just left this one on the back burner, which was good actually because it turned out quite differently to the way it would have been a few years ago, I think, and then I just picked it up again.

I’d planned to get back to it in November last year but I came off these dates I’d been playing in Europe and I just couldn’t be bothered. I spent November and December just going, ‘oh I should be working on that album and I just can’t get my head around it’, and I finally got back to it in January. We had to turn it around very quickly because I’d just been sitting around not working, but it really was very different as a result.

Actually no, that’s probably not true because in fact during November and December I probably wrote about three or four of those songs, the little ones that are in there and put it together, so I wasn’t doing the hard work, the 99% perspiration bit, but I was waiting for the songs to fall into place I think.

How does the song writing process work for you – do you write music or lyrics first?

Mick Harvey: Sometimes there’s some music there. Usually I sit down and I write some words actually. If there are words then I think I can sit down and work out how the music’s going to be, it tells me what music to put to it so it’s more round that kind of way.

Why do you think your recent albums have had a conceptual theme?

Mick Harvey: I really don’t know, I think that’s the only way I would really write. I think if I was just writing random songs that they’d be few and far between, as they were.

It’s really the last couple of projects, where I started things and suddenly there was a theme to hang ideas off, that I was able to get an idea about what to write, because it seemed like there was something that needed to be done and I knew what it was meant to be about ostensibly so I could come and get started on something. But I tend not to write stuff really, I’m not really a writer in that way, so having the themes to write on has been very helpful.

So I imagine if I do something else it will probably be some theme or another, I can’t imagine what it will be though.

You’ve already covered two big ones – death and love.

Mick Harvey: Yeah, in a way. They’re only covered from certain angles on those things; they’re not really all-encompassing. The Sketches From the Book of the Dead album’s really about memory, it’s not really about loss or death in particular, so it’s only looking at an aspect of that, much as this album’s really looking at certain aspects of the subject because it becomes referential. Oddly, it kind of reverse psyches itself.

I started with a few of the cover songs, these songs that were still on my list that I wanted to do and I realised they were mostly love songs, song about that subject, not really love songs, but songs about the subject of love and I wondered what on earth to do with it, and realised that I just had the idea to put it into that kind of fake story in a way, so that I could find a path through the thing and figure out what I wanted to say about it.

[quote]it’s a bit

ridiculous aping

a blues band

or being a

reggae band[/quote]

The funny thing is that it comes back round and actually kind of becomes a commentary on love and the popular song in a way, because it’s so all pervasive in modern culture, this romantic love subject in songs. What’s that all about? Why is that so prevalent? It’s just relentless. So that’s at issue as well throughout the album and it’s really asking questions about that as well – what’s that about? It’s like some kind of internalised escapism from anything bigger.

It’s a huge issue; it’s a weird thing in popular culture that this stuff goes on. It becomes a distraction. It’s literally a diversion, entertainment to distract you from what’s going on, or what you could be looking at about what’s going on in the world or in the universe or whatever. So you have these love songs and you sit around looking at your own navel.

So after I’d done the first two albums, when I’d got back to my list of songs that I’d started off with and it was like, why have I left those songs behind, why didn’t I record those songs yet when they’re all kind of about that subject? They were songs I really wanted to record, but that made me wonder why I’d left them behind as well.

I think that’s part of the reason so to have an album about that subject was a bit weird for me because it’s actually something I was obviously trying to avoid. So I’m confronting some kind of weird demon as well, my own displeasure with the subject matter.

You’re the son of a vicar and the new album has a song adapted from a hymn – how strong is the religious influence in your work?

Mick Harvey: It’s pretty hard for me to analyse that really. Probably my rejection of it, but I’m not quite sure in what way. I’m probably, deep down, I’m very much a kind of Christian Humanist in the way I behave, which is really the way our society’s structured anyway, it’s depending on some charitable underlying condition for things to operate. I kind of agree with those kind of principles and that comes from Christianity.

A lot of behavioural expectations come from that and I agree with the ideas, with that lifestyle basically, and that would have come very strongly from my parents and their religion so I suppose it has played a part in that kind of thinking. It’s pretty deeply entrenched in a way, but God is a bit of a mystery.

Part 2 of this interview, where Mick talks about Nick Cave, murder and PJ Harvey, appears here.

Photos: Carl Byron Batson