Mind and Brain

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]W[/dropcap]henever we think about thinking, we think about mind. It is a common commendation to say of someone that he or she has a good brain. There. In just two sentences we move seemingly seamlessly from minds to brains; and we thereby license our use of ‘mind’ and ‘brain’ as synonyms.

Neuroscience

Great strides in neuroscience promise to bring into focus better understanding of what minds are. Increasingly, we have come to think of minds as being ‘seated’ in the brain or, more extendedly, in the nervous system overall.

Let’s start by chatting with an ancient.

Aristotle

How could an organism come into being out of ‘something quite amorphous’? This is a problem Aristotle faced when he set out his thoughts on ‘form’. Put plainly, Aristotle divides the world up into form and matter. A statue of Winston Churchill, made of bronze, had the alloy of copper and tin as its matter, and the shape of Churchill as its form. But we could melt down the statue of Churchill and make it into a new statue, perhaps of Ann Widdecombe. The matter would remain the same even though its form would have changed.

Some changes, however, are accidental, whilst others are essential. The former changes are accidental if they do not change the fundamental nature or identity of the individual undergoing the change. If they cause the nature or identity of the individual to change then that individual ceases to be the individual that it is; it ceases to exist.

Since the shape of Winston Churchill is not essential to the nature and identity of bronze, we think of the bronze as enduring through change as its shape alters from that of Churchill to Widdecombe.

Aristotle on Causation

Aristotle has four categories of causation. These are,

- The material cause: “that out of which”, e.g., the bronze of a statue.

- The formal cause: “the form”, “the account of what-it-is-to-be”, e.g., the shape of a statue.

- The efficient cause: “the primary source of the change or rest”, e.g., the artisan, the art of bronze-casting the statue, the man who gives advice, the father of the child.

- The final cause: “the end, that for the sake of which a thing is done”, e.g., health is the end of walking, losing weight, purging, drugs, and surgical tools.

A problem arises for Aristotle. Suppose we slightly complicate the bronze being turned from Churchill shape to its being Widdecombe shape. The new question is, ‘What is the material cause of a sponge-cake?

- 125g/4oz butter or margarine, softened

- 125g/4oz caster sugar

- 2 medium eggs

- 125g/4oz self-raising flour

And here is the method by which the ingredients are worked to become a sponge-cake,

- Heat the oven to 180C/350F/Gas 4.

- Line two 18cm/7in cake tins with baking parchment

- Cream the butter and the sugar together until pale. Use an electric hand mixer if you have one.

- Beat in the eggs.

- Sift over the flour and fold in using a large metal spoon.

- The mixture should be of a dropping consistency; if it is not, add a little milk.

- Divide the mixture between the cake tins and gently spread out with a spatula. Bake for 20-25 minutes until an inserted skewer comes out clean. Allow to stand for 5 minutes before turning on to a wire rack to cool.

- Sandwich the cakes together with jam, lemon curd or whipped cream and berries or just enjoy on its own. (BBC 2018)

The list of ingredients provides us with, in Aristotle’s terms, the material cause. The method of cooking the cake is Aristotle’s efficient cause – what you must do to the ingredients to get them to become the sponge-cake. The sponge-cake being the cooked combination of the ingredients is the form that the ingredients take when the efficient cause is applied to the material cause. And last, we have the end to which the sponge-cake is aimed – that of being a sweet, light, bite to enjoy at tea-time with friends.

Human Beings

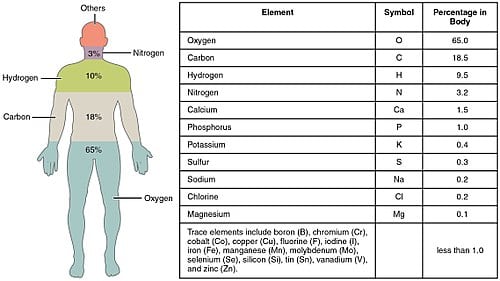

More complicated yet, let us think of a human being. Let’s call him Charlie Chigwell. 93% of Charlie Chigwell, we will not be surprised to hear, comprises, Oxygen, Carbon and Hydrogen. There are other elemental ingredients, too, as specified in the following diagram.

The formal cause of Chigwell will be the arrangement in which these materials are brought together. That is what constitutes the formal cause. It is the ‘organizing principle’.

Now, if the list of ingredients constitutes the material cause of Chigwell, and the bodily organization, the formal cause, we can ask about the efficient cause. How is it that these ingredients come together to bring about Chigwell? The answer, we are to suppose, is that they are brought together in an environment so that the act of combining provides a structure exemplified as a formal cause.

The final cause is what Charlie Chigwell is ‘designed’ to do – to eat, to walk, to work, to think, and so on. The final cause includes thinking. Chigwell would not be a human being if he was void of thought.

Human Beings are more than just quantities of Stuff

So, here’s the difficulty. If butter, sugar, eggs and milk behave in a certain way when treated, it is because of their material properties and we can understand that this is to do with heating for a certain time, with the way the ingredients react to each other and so on. We can understand the cake’s coming about because of the material conditions obtaining in a cooking environment such as a kitchen.

But in the yet more complex case of Chigwell, how do we get from 93% Oxygen, carbon and hydrogen – and the rest (7%) – to thoughts? Moreover, however complicated the sponge-cake might be, how is it possible for us to get out of the causal nexus of the physical world and into the structure of thought itself?

Wittgenstein Against Reductionism

The great twentieth century philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein cautioned against the idea that all thought processes should be ultimately explained by processes in the brain.

608. No supposition seems to me more natural than that there is no process in the brain correlated with associating or with thinking; so that it would be impossible to read off thought-processes from brain-processes. I mean this: if I talk or write there is, I assume, a system of impulses going out from my brain and correlated with my spoken and written thoughts. But why should the system continue further in the direction of the centre? Why should this order not proceed, so to speak, out of chaos? The case would be like the following – certain kinds of plants multiply by seed, so that a seed always produces a plant of the same kind as that from which it was produced – but nothing in the seed corresponds to the plant which comes from it; so that it is impossible to infer the properties or structure of the plant from those of the seed that it comes out of – this can only be done from the history of the seed. So an organism might come into being even out of something quite amorphous, as it were causelessly; and there is no reason why this should not really hold for our thoughts, and hence for our talking and writing.

609. It is thus perfectly possible that certain psychological phenomena cannot be investigated physiologically, because physiologically nothing corresponds to them. (Wittgenstein 1975)

Thought does not fit easily within a physicalist world view. That is what tempted Réne Descartes to posit at least two types of substance. (A substance is a kind of thing or stuff.) He thought there were both physical (material) and non-physical (immaterial) objects. A brain is a physical object. A mind is not. It is, according to Descartes, a soul.

How Can The Mental Causally Effect The Physical?

Descartes dualism brought problems of its own, not the least of which is the interaction between these two sorts of substance.

I can decide to raise my right hand, say in three seconds time. After a count of three, I duly raise my right hand. What caused me to raise my right hand, we might think is an intention. I acted on that intention and my right hand was raised.

But how can something as immaterial as a thought, a mental event, cause an event in the material world?

Descartes’ Dualism

To this Descartes suggested a rather unconvincing answer. The mental interacts with the physical in a small gland seated in the brain – the pineal gland. That answer will not do. It simply locates a place where the interaction is to occur. But it fails to answer the question of how something like an arm, located in the physical world, can be caused by a mental prompt which, ex hypothesi, does not occupy space at all.

In his journal for 26th September 1937, Wittgenstein writes of two plant varieties, A and B. He then asks us to consider the following. The seed from variety A, always produces a plant of type A. The seed from variety B, always produces plant type B. Further we are to imagine that there is no physical difference whatever between the two seeds. The explanation for the constant lineage of A seeds – A plants, and B seeds – B plants is given in the history but not in the physical structure of the seed. (Wittgenstein 1976)

By analogy, we are asked, couldn’t it be that my memory of an event in which I was involved thirty years ago is explained fully and only by the fact I was involved in the event thirty years ago.

The paragraph in Zettel consequent to the two quoted above is this,

610. I saw this man years ago: now I have seen him again, I recognize him, I remember his name. And why does there have to be a cause of this remembering in my nervous system? Why must something or other, whatever it may be, be stored up there in any form? Why must a trace have been left behind? Why should there not be a psychological regularity to which no physiological regularity corresponds? If this upsets our concepts of causality then it is high time they were upset. (Wittgenstein 1975)

Wittgenstein calls for an overhaul of our conception of causality; one in which we pay due credit to the intuition that mental ‘goings-on’ are part of the furniture of thinking, acting, and living -as a human being. Others, worried that the purely materialistic conception of causality leaves thinking (and, in particular, consciousness) floating unanchored in the grinding continuum of the real world. The mental, so adrift, must be thought something like a dream world – a world of mere appearances which float like mental steam above the cranking of the gears. Such a diminished view of the mind is dubbed ‘epiphenomenalism’.

Epiphenomenalism

The contemporary philosopher, Jaegwon Kim, notes,

Few philosophers have been self-possessed epiphenomenalists, although there are those whose views appear to lead to such a position. We are more likely to find epiphenomenalist thinking among the scientists who do research in neurophysiology. They are apt to treat mentality, especially consciousness, as a mere shadow or afterglow thrown off by the complex neural processes going on in the brain; these physical/biological processes are what at bottom do all the pushing and pulling to keep the human organism properly functioning. (Kim 2008)

And so neuroscientists, such as Semir Zeki, are happy to locate very precisely the regions of the brain which are regularly activated by certain sorts of stimulus. These include brain activity current when patients are asked to think of, or to imagine, certain objects events or scenes.

But is location any better at solving our mind/body problem? After all few, if any, philosophers believe that thought is possible without neural or some equivalent physiological basis.

On the 31st July 2018, a news release (see link, next sentence) provided an account of a boy who had a lobectomy; and whose phenomenal, if partial, recovery relocates various brain functions. Thus, we are provided with a ‘glimpse’ of the remarkable plasticity of the brain.

The problem remains and is exacerbated by this further isolation of the mind from its physical seat. For where now is Zeki to look for regularities of brain activity and thought content?

To leave the question hanging: two thoughts.

-

- Grass is green

- Something is green

These two thoughts, whilst identifiably independent of each other are, nevertheless, related. By implicature, the truth of (2) is guaranteed by the truth of (1). Contrapuntally, the falsity of (2) guarantees the falsity of (1).

But how can an efficient cause, together with the material cause, account for someone who holds (1) but does not hold (2). On the Aristotelean view, (1) and (2) are not only independent thoughts, they are necessarily independent. Ex hypothesi, the material conditions (in the brain) under which (1) is thought to be true would have to cause the material conditions (in the brain) under which (2) is true. But that would make it impossible for anyone to hold (1) true and (2) false. Surely that cannot be the case.

Or: suppose a group of subjects regularly believed (1) but not (2). We would think them wrong. But how could we think that if having believed (1) they were physically caused by their neural goings-on to think (2), they were wrong. That path is only open to us if we see that (2) must follow from (1) as a deduction. In short (1) does not cause (2). Otherwise we should risk the edifice of mathematics in total.

References:

BBC Food Recipes (accessed on 2nd August 2018)

Kim, J (2008) ‘Mental Causation,’ in William G. Lycan and Jesse Prinz, (eds.), Mind and Cognition, Oxford: Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, L (1975) Zettel, Oxford: BasilBlackwell.

Wittgenstein, L (1976) ‘Cause and Effect: Intuitive Awareness’, in. ed. R. Rhees, trans. Peter Winch, Philosophia, vol. 6., nos., 3 and 4, Sept – Dec.

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.