Peter Womersley’s High Sunderland (1958), situated in a pine forest on the Scottish borders

A time of reflection

An aesthetic error occurs when we wrongly assume some theory of art that is false. In these times of reflection, locked into our flats and houses; and chained to our desks, we might consider the pros and cons of living life strictly according to ideas – as opposed to pragmatism and its going with the flow, meandering through life. Reflection is undertaken to get us from the appearance of things to newer, deeper ideas about those things, thereby changing the initial appearances for newer, richer appearances.

High Sunderland, High modernism and an aesthetic error

High Sunderland is a high concept modernist building, a house and a piece of fine art – at least, according to its owner Bernat (Beri) Klein, the textile designer. It was commissioned in 1956 and completed in 1958.

In the review of the memoir, by Klein’s daughter Shelley, Blake Morrison writes that when she,

“moved back in with her farther Beri after her mother died, she brought some old furniture with her. He didn’t want it in the house: a Victorian chair would compromise the modernist vernacular, he said. He objected to her pots of herbs, too: putting them on the kitchen windowsill would ruin the rectangular symmetry. They had had these arguments since childhood, when he stopped her having a Christmas tree. To Beri, the house was a work of art, a gallery for living in, and nothing must detract from its aesthetic.” (Morrison 2020)

Austerity or absurdity?

The hallway had a solitary piece of furniture, a Danish chair, “on which it was forbidden to sit” (ibid.)

That all depends upon whether you think that Bernat Klein was right to think of his house as a piece of art, as one might think of a painting or a sculpture as a work of art, there to be contemplated as a formal arrangement, along the lines of modernist doctrine. No Christmas tree is bad enough; but “no sitting down,” is an injunction too far; much too far.

The aesthetic mistake made by Klein senior is not that he thinks a work of architecture is a work of art. It is. It is that he thinks there is some overall conception of art that can be arrived at independently of any particular kind to which the work belongs. Klein treats architecture as if it is mere form, just as modernist painters and sculptors were encouraged to think of painting as mere form.

Architecture accommodates our lives

Architecture, as an art-kind, is committed to accommodating the lives we live. That commitment is central to architecture and disregarding it, as Klein was moved to do, is to fall into aesthetic error. Works of architecture are not paintings and they are not sculptures. Paintings are for looking at and looking into. Sculptures are for looking at, through and around. Paintings offer views onto spaces we do not inhabit. Sculptures occupy space that is literally continuous with ours but metaphorically distant from it – as when I look at Rodin’s images of hell.

Architecture, by contrast, frames our lived lives. Even when it frames heavenly visions, it is to offer us a glimpse of a place now continuous with our lives. In churches we are transposed from this world into the realm of the sacred, if only, perhaps, in imagination. The medium of architecture is not the medium of either painting or sculpture.

Architecture is a specific art-kind

Klein’s aesthetic error was to conceive of architecture as if modernism was an all-embracing art-kind. At least since Kant, however, philosophers have sorted the arts into medium specific kinds. It is then the job of philosophy to give account for medium specific inclusion to any work of art.

Eisenmann against functionalism

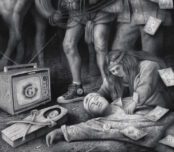

Arguing against functionalism – a putative candidate for architecture’s medium specificity – Peter Eisenmann sought to make architecture into a formalist art. Here is a piece of video made by architecture students at Taylor University in the USA. In it we see a column that carries no weight and a double bed that is divided in two in accordance with the formal requirements of House VI.

It is hard to grasp what rules of composition might amount to in the absence of purpose.So it is very odd to think that conceptual composition, whatever that might amount to, trumps dining with company or Mr and Mrs Frank sleeping in a bed together.

The aesthetic lives of Carmelite monks and nuns

The life of monks and nuns – spent in the presence of the redeemer – might be thought aesthetic. It is a contemplative way of life, full of dignity and humility. Both monks and nuns take a vow of celibacy and poverty. They lead a spiritual life in preparation for heaven.

But would we think such lives wasted if it turns out that religion is the wrong horse. (Of course, if it is the wrong horse we shall never find out.)

Here is Ludwig Wittgenstein pondering such matters,

“What inclines even me to believe in Christ’s Resurrection? It is as though I play with the thought. – If he did not rise from the dead, then he decomposed in the grave like any other man. He is dead and decomposed. In that case he is a teacher like any other and can no longer help; and once more we are orphaned and alone. So we have to content ourselves with wisdom and speculation. We are in a sort of hell where we can do nothing but dream, roofed in, as it were, and cut off from heaven. But if I am to be REALLY saved, – what I need is certainty – not wisdom, dreams or speculation – and this certainty is faith. And faith is faith in what is needed by my heart, my soul, not my speculative intelligence. For it is my soul with its passions, as it were with its flesh and blood, that has to be saved, not my abstract mind. Perhaps we can say: Only love can believe the resurrection. Or: It is love that believes the resurrection. We might say: Redeeming love believes even in the Resurrection; holds fast even to the Resurrection. What combats doubt is, as it were, redemption.” (Wittgenstein 1980 33e)

The religious life understood as aesthetic

Here, we might think of Wittgenstein as taking a holiday from intellection, as he sometimes advised others to do, cruising instead in the language-form of aesthetic puzzlement. What he writes here is more akin to poetry. It does not belong in the world of scientific dispute and confirmation – to the world of fact and figure. If the Carmelites are in error, it is not an aesthetic error but a metaphysical error.

The two architects, it is here claimed, have fallen into aesthetic error. The monks and nuns cannot be certain – or, perhaps, they are as certain as anyone else might be. But Wittgenstein makes no such aesthetic error; nor does he state that he believes in the Resurrection. The language of religion – its spiritual dimension – is close to that of aesthetics.

In reflection about architecture, as an art, we need to think of it in terms of the way in which we live our lives. That will guide us away from the errors into which Berat Klein and Peter Eisenmann have fallen.

References: Morrison, B., (2020) ‘{Memoir} A moving and bracingly honest account of a father and the modernist home that obsessed him,’ in The Guardian Review, 25/04/2020

Wittgenstein, L. (1980), Culture and Value, Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.