[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]culpture trails live and die on how presentable the host town is.

As a municipal tour de force, the concept can be a boon to a town’s fortunes, particularly when the event comes with attendant media attention or viral furore. Cast your mind back to the 1990s and the roving spectacle of life-sized cows decorating the streets and squares of various European cities – a pre-Instagram myriad of picturesque Instagram moments which leveraged the still-burgeoning penchant for the connected public to self-publish images of themselves against a backdrop of hip locales and fibreglass cow structures.

In terms of municipal marketing, 21st century post-industrial rebranding and budget airline getaway attractiveness, those cows (each decorated/reimagined by local artists) scattered around strategic locations, were a solid investment.

The phenomenon was copied, watered down and eventually rendered stale by repetition. Once we had the concept repeated worldwide in ever more diluted forms (horses, pigs, or in Bristol’s case, statues of Nick Park’s Grommit), the social media allure of the quirky subject-with-sculpture-against-cityscape died with it, and moved on to its perennial preoccupation with barely-edible-but-photogenic restaurant meals and cats being amusing.

Whither then, the sculpture trail? Perhaps now that the feelgood populist version of the idea has been consigned to the scrapheap (to be re-launched in an ironic, retro, kinda oldskool vibe, yeah? way next decade), some focus can be re-applied to the vision of the featured sculptor, or even the host town as backdrop. Neither aspect, it must be noted, being forgrounded in the aforementioned cows project.

Public sculpture is an artistic oddity, given that it is so trammeled by the constraints of the application. Our most common interaction with contemporary sculpture (outside of the mostly figurative representations we see on statuary or architecture) is the comissioned structures we see on the embankments of motorways, themselves the product of artists working to a strict remit that the artwork be visually subdued to the extent that it does not distract the attention of the driver. A singular constraint, akin to commissioning contemporary composers to create a symphony which does not draw the ear, or a dramatist to write a play without event.

Can the sculpture trail, then, rekindle a public interaction with contemporary art, whilst actually demanding enough attention to appreciate an artwork without the pesky business of attending a gallery or steering a vehicle? It’s worth a try anyway, depending upon how generally presentable your town happens to be. The trouble with placing artworks around a municipality for public perusal is that it really depends on how wide a sweep of safe, clean and secure display spaces are available. Structural sculpture may well create an aesthetic, but a display space littered with pizza boxes, chicken bones and hypodermic syringes may tax the viewer’s ability to experience the sublime.

No such issues mar the experience of Monette Loza‘s town-wide installation in Hossegor (South-West France). A fin-de-siecle vernacular architecture crispened at the edges by decades of lucrative golf and surf tourism is the pervasive architectural cue to the town, along with sea-lagoon promenades and the enduring French mileu of lavish municipal planting, generous parks and sun-dappled games of petanque at midday. With or without complementary sculpture, it is a visually pleasing place.

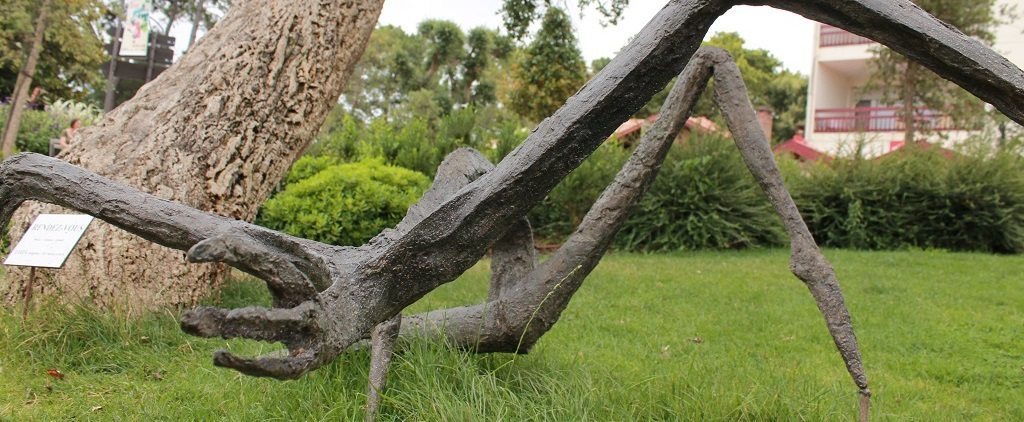

Loza’s works, placed unstintingly around the environs of the town, hover between the safe and the satisfyingly disturbing. Of the safe examples, her recreations in treated steel of palm trees and cypress-like shubbery seem lacking in any metaphor – there are enough of the genuine article growing within eyeshot to render the sculptures obsolete. Her more triumphant efforts are the creeping insectoids of ‘Rendez-vous’, unsettling in a manner extremely reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois’s arachnid ‘Maman’ at the Bilbao Guggenheim, and the humanoid dancer figure of ‘Grande Plie’ on the lagoon bridge (inset above). Elsewhere, the exuberant pink arabesques in enamelled steel of ‘St. Valentin’ offer a frivolous and pretty contrast the the dull 1990s office architecture of their backdrop which, if not quite setting in motion an emotive internal dialogue on the nature of society, is certainly a pleasant object to look at.

Perhaps fittingly, Loza abandons only the frivolity and effervescence of her botanical creations for clean lines and, frankly, dull structure at the entrance to the Hossegor’s golf club. ‘Passage’, a scrolled and pointed sheet of steel is welded onto a roughly polished base, presenting a two-metre lump of what could be a corporate logo in three dimensions. After the quirks and humour of her works elsewhere, it verges on insult. If metaphor is slightly lacking in certain of Loza’s displayed works, it is not the case here. Golf – corporate and boring? The implication is clear.

Monette Loza’s Sculptures Monumentales currently on display at various locations in Hossegor, Aquitaine. Photos by the author.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.