[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]usic has many values, but is it truly worth a life?

Music is something which plays a massive role in society and has done so throughout the ages. From hymns and other religious themed observances; to becoming a vehicle for voicing an opinion where it might not be allowed to be voiced in normal; words to expressing an idea, emotion or concept. It is such a vast, flexible and diverse vehicle for communication, even if its pivotal importance is sometimes overlooked.

But in some parts of the world, music isn’t as flexible and communicable as it should be.

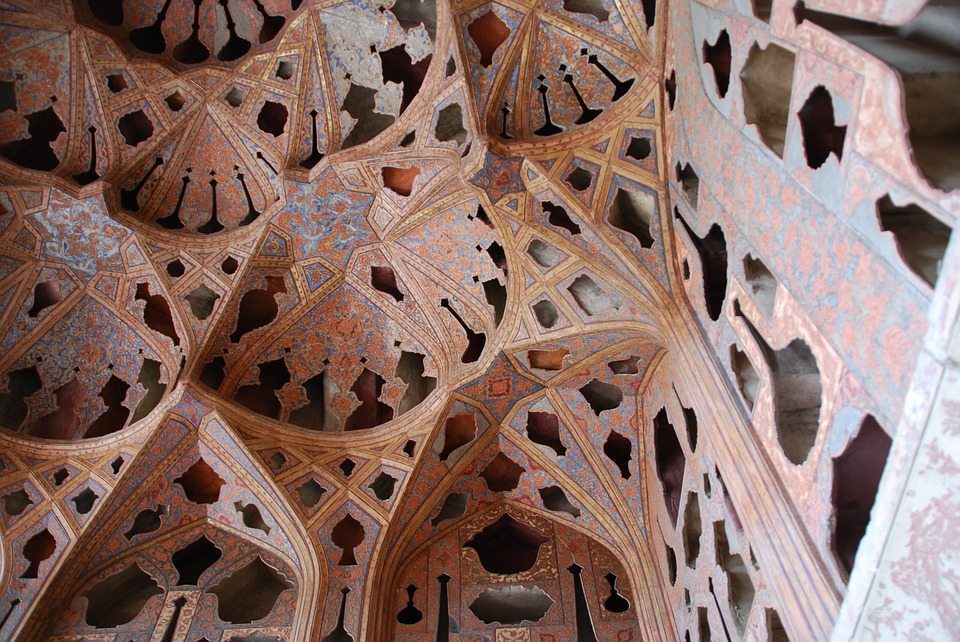

In Iran in 1979, there was revolution in the air. Fuelled by a hard-line religious approach, a lack of faith in the monarchy which had ruled the country for over two millennia, and a growing feeling amongst the populace that change was needed, the Grand Ayatollah Khomeini helped orchestrate one of the biggest power shifts in the Middle East which turned a monarchy cordial with the Western world into a religious republic which condemned many. Hostage takings, embassy sieges, Fatwas and tight control led to a drastic change in the way things were run in Iran and, despite some short-lived periods of progress, still are to this day. The uprising and unrest some years ago with regards to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s government ‘promised’ more freedom, but brought only more hard-line authoritarianism.

But where does this link to music?

Some reading into the subject is required. Across much of the Islamic world, there are plenty of subjects which fall under the umbrella of sanctimonious, blasphemic, heretical and other anti-belief orientated descriptions. Music is often one of these subects. Whilst the North African countries like Morocco often take a more liberal approach to things cultural, and whilst there is evidence of Israeli and Palestinian music crossing the religious/cultural divide (and even talk of a growing heavy metal scene in Baghdad), Iran remains the champion of sticking to dogma, right down to the tiniest of infringements.

With the government regulating music via the Ministry of Ershad (The Ministry of Culture & Islamic Guidance), it is certainly difficult for those who aim to create and facilitate musical endeavours. Unsurprisingly, given its stance of sticking to the beliefs set up in the wake of the revolution and change period (1979-1983), more contemporary genres of music (most notably those popular in the western world; Rap, Rock, Heavy Metal) are often outlawed.

Because these genres are outlawed under religious grounds and thus labelled heretical and blasphemous, it is no surprise that the consequences for musicians who perform in these genres include being labelled as ‘Kaffirs’, tried without evidence other than religious related observances, as well as heavy financial and physical punishments. Execution, without exaggeration, is a possible outcome.

Orlando Crowcroft’s Rock In a Hard Place details some of these tales – bands who were helping to create a thriving underground scene, venues operating like speakeasy bars from prohibition era America, word of mouth and almost covert operations to get people to gigs without being caught. It all seems a little surreal, almost like some kind of Orwellian nightmare or the plot to a really bad movie which comes on the TV at 2am.

Farfetched? Crowcroft’s book documents reality. It isn’t simply a collection of tales to create a gripping narrative; it is the reality for those who perform these genres of music. One very recent example of this is the fate of the heavy metal band Confess. The group were arrested in 2016 and had a whole raft of charges lobbied against them. Formally, the rap sheet included “blasphemy; advertising against the system; forming and running an illegal and underground label in the satanic metal and rock style; writing anti-religious, atheistic, political and anarchistic lyrics; and interviewing with forbidden radio stations.”

Thankfully, the band has had the threat of execution removed from them and have since been lying low, but this is the reality for musicians in Iran. Even traditional folk acts aren’t exempt from the persecution of hard-liners. Folk group Lian were granted permission to perform in their hometown of Busher Port when Hezbollah supporters staged an illegal blockade of the venue, staging prayers in the street around it, thus disrupting many from entering.

With these as just two of many examples of how life is for a musician in Iran, you have to wonder, is this really worth the cost?

The music enthusiast in me would suggest ignoring the consequences as, to my mind, the restrictions in place in Iran with regards to creativity and freedom of expression are nigh on absurd (Case in point: The album Melancholia by Heterochrome ).

This is not me being insensitive about other religious and cultural beliefs (as an Atheist, I accept people can live their life to whatever decree they believe, I just don’t buy into the whole higher power notions and how centuries-old texts should dictate our life in the 21st century!), but when the cost is one’s life, then the absurdity becomes a lot colder. Suddenly beliefs and creeds become hotbeds for discussion, conflicts of interest, and a very precarious balancing act between valuing freedom of expression and becoming a martyr (when the only people who are likely to benefit from your sacrifice are those who are unaffected by such rules as those in Iran).

So I ask, what is the cost of music, and is it as valuable as a life?

Born in the 80s, grew up with the 90s and confused by the millennial generation, I am Peter, more commonly known as Fraggle (long story, don’t ask, details are a little hazy!)

With a degree in biochemistry, an ever growing guitar collection and a job handling medication, things are far different to how I expected them to have turned out, but the one thing which hasn’t changed is how important music is in my life—it is one of my main passions, be it playing it, listening to it or attending it and experiencing it in the live setting (the way it is meant to be).

Blessed with a ‘proper punk/metal spirit’ (quote from Kailas), you will often encounter me at gigs or festivals with a beer firmly clutched in one hand and shirt in the other… Or these days, a pen and notepad too, maybe a camera if needed.