[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]L[/dropcap]iz Orton’s large photographs from the series Splitters and Lumpers were the inspiration for this thought-provoking show, curated by Tom Jeffreys.

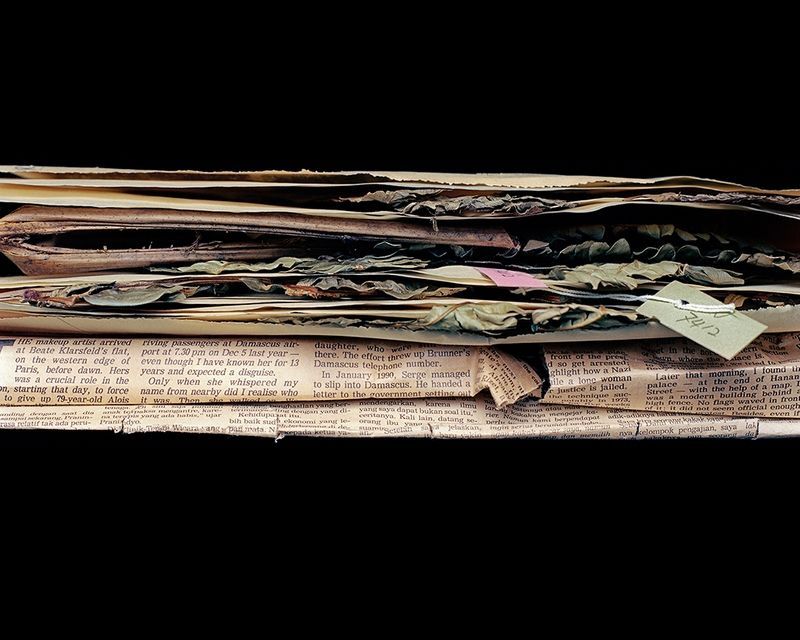

Given access to the Herbarium at Kew Gardens, she chose to focus on the as-yet unclassified plant specimens, their nameless curled leaves, curious seed pods or feathery flowers poking unmanageably out from between the corrugated cardboard and paper folders they are kept in.

Photographed against black, these sumptuously detailed images recall Dutch Still Life paintings, with their piles of exotic fruits and dead animals. Rather, however, than a celebration of triumphant domination over the natural world, Orton’s photographs are a poignant reminder of human failure. For all the apparent omnipotence of our universal scientific systems for the analysis, classification and control of nature, she still eludes our grasp.

Liz Orton, Splitters and Lumpers 1, 2012 – Image courtesy of the Artist and GV Art gallery, London

The title of Orton’s work, Splitters and Lumpers, makes mock of our zeal to characterize and differentiate, as each gorgeous specimen spills defiantly, irreducibly, from its brown square folder.

[quote]For all the

apparent omnipotence

of our universal

scientific systems for

the analysis, classification

and control of nature,

she still eludes our

grasp[/quote]

Nature Reserves is all about our human tendency to put things in boxes, real and metaphorical. Jeffreys has raided UCL’s geology and zoology collections and the South London Botanical Institute to represent the institutional apparatus of our deep fascination with nature and natural history.

Drawers of volcanic rocks and minerals; two glass cases of labels missing from their zoological specimens, dating back over 170 years, and two four-storey Edwardian iron cabinets containing ferns evoke a history of anachronistic systems of classification, even as they honour the pioneering scientists who confidently gathered them. Unsurprisingly, these specimen collectors – Dr Johnston-Lavis, Robert Edmond Grant and Allan Octavian Hume – were all men.

The twelve artists in this exhibition, selected from over 1000 open applications, are all women, and it is perhaps this gender difference that enables them to discover in failure and supersession not shame but beauty and excitement.

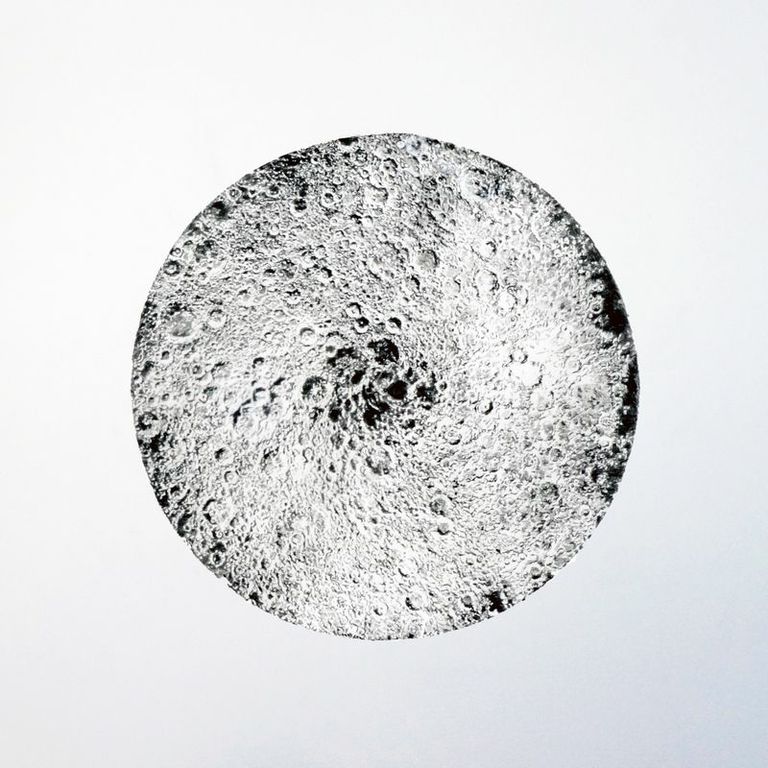

Anais Tondeur – Mutation of the Visible (After Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter v2), 2013, Image courtesy of the Artist and GV Art gallery, London

Thus Anaïs Tondeur, a visual artist who lives and works in Paris, has produced a pungent series of five drawings of the moon, each of which reflects a different stage in man’s perception of our celestial neighbour. Mutation of the Visible re-presents in meticulous, humble graphite images created in the prescientific era, in the eras of optical instruments and over the last fifty years of space exploration.

British artist Laura Culham meanwhile has made Weeds, 111, a moving collection, in neat white paper boxes, of exact reconstructions, in till receipt paper and glue, of the nameless weeds in her garden. Helen Pynor’s gelatin silver prints The Life Raft make beautiful the collapsing remnants of historic collections of crustacea and insects, while Pauline Woolley’s evocative but ultimately elusive series of images about Boulby Potash Mine, falling apart from the earth into the hands of man, stirs our sense of the earth’s profound mysteriousness.

Three artists explore different kinds of intimacy between man and nature. Hestia Peppe offers Microbial Familiars, a site-specific installation of vessels of live Kombucha tea, which have been cultivated in different friends’ homes, an amusing reflection on symbiosis, while Victoria Browne exhibits her exquisite stone lithograph, Caught the Wild Wind Home, of a coppiced tree, a more ambiguous response to man’s desire to control.

Amy Cutler – PINE – Image courtesy of the artist and GV Art gallery London

It is Amy Cutler’s installation, PINE, however, a projection onto a section of tree that has experienced “forest trauma”, lines from a poem by holocaust survivor, Charlotte Delbo, that offers the most radical image of interrelatedness. The juxtaposition shocks partly because we resist such analogies, but also stirs an ambivalence about all our efforts to make nature speak.

Perhaps, in the end, Nature reserves the right to remain silent.