[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he Idea of newness is an essential part of the function of art in modern times but what does that mean and how does newness form and change? Are we all prone to long for a past that never was or a future that can never be?

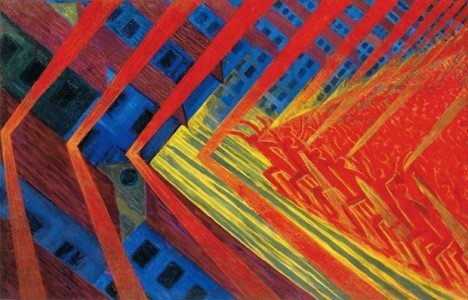

Luigi Russolo The Revolt 1911

The energy and allure of newness is known to anybody who feels dulled by habit and restricted by established ways of thinking especially when these stale habits are given credibility from the masses and propped up by powerful institutions. That this feeling should become a battle between the avant-garde and tradition is a failing in anyone or any institution which wants to embrace the new rather the battle is and should be understood as one interpretation of tradition opposing another, one view which see tradition naturally evolving and building the foundation for the new and the other which attempts to freeze values and force each new generation into repetition,

“So let them come, the gay incendiaries with charred fingers! Here they are! Here they are!… Come on! set fire to the library shelves! Turn aside the canals to flood the museums!… Oh, the joy of seeing the glorious old canvases bobbing adrift on those waters, discoloured and shredded!… Take up your pickaxes, your axes and hammers and wreck, wreck the venerable cities, pitilessly!” The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism Original publication in French: Le Figaro, Paris, February 20, 1909 This English-language translation COPYRIGHT ©1973 Thames and Hudson Ltd, London.

Newness of the Past

Marinetti’s words above which make a persuasive case for an attack on the past and its physical manifestations could be seen as a description of Russolo’s painting, we recognise the city its tumult and the ‘gay incendiaries’ the colour of fire running to destroy what keeps them down, however we might also see how this painting like all futurism of this sort is as Wyndham Lewis reflected, ‘Impressionism up to date’ that Lewis meant this as an insult is more to do with drawing a distinction between his own movement Vortisism and Marinetti’s attempt to assimilate it into Futurism, he was right though.

The futurists replaced nature with technology and combined colour with movement. Lewis’s observation is all the more convincing if we remember it was Cezanne a post-Impressionist who planted the seeds of Cubism in Braque and Picasso whose studies were the starting point of Futurism. This kind of simple insight is lost in the seduction of posturing against tradition.

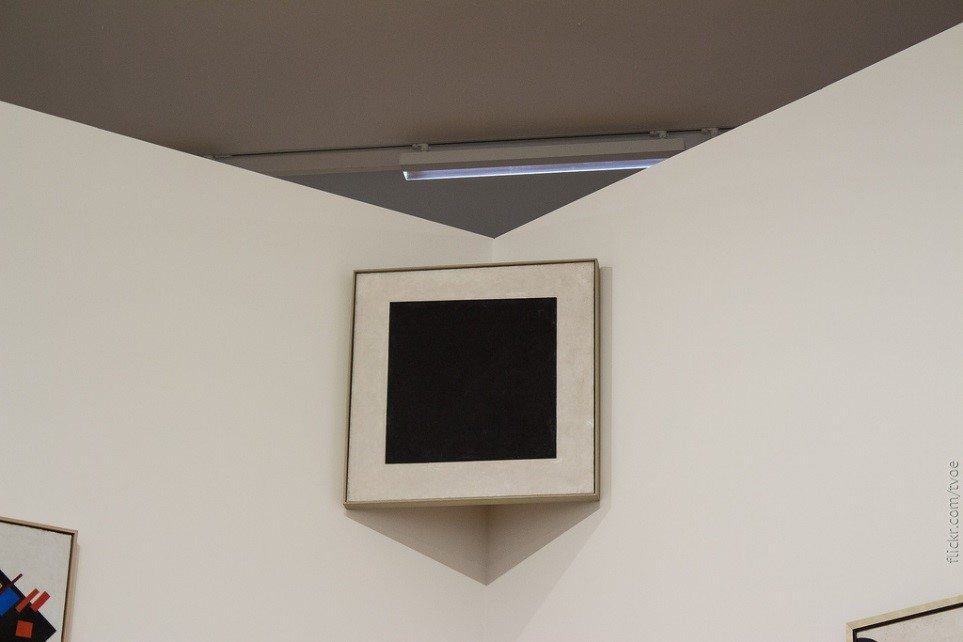

Kazimir Malevich, The Black Square, 1915.

Malevich showed the ‘Black Square’ in the last Futurist exhibition it was placed as above like an icon and as such it takes on a kind of religious tone its simplicity is the cause of much scandal among an audience who is encouraged to see it as a kind of swindle or con,

“Malevich is monumental not for what he put into pictorial space but for what he took out: bodily experience, the fundamental theme of Western art since the Renaissance. His appeal to Americans isn’t surprising. Apart from a peculiarly Russian mystical tradition, which he exploited—evoking the compact spell of the icon, as a conduit of the divine—his work amounts to a cosmic “Song of the Open Road.” It conveys sheer, surging, untrammelled possibility. This quality seemed in synch with the Revolution of 1917. It wasn’t—which Malevich was painfully made aware of, first by his rivals in the Russian avant-garde and then, conclusively, by the regime of Joseph Stalin.” Schjehldahl, Peter. “The Prophet: Malevich’s Revolution”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

There is a yearning for something new and perhaps also a need to push out all the clutter which is in line with Marinetti’s quote but he is clearly also and without any irony evoking the status of a spiritual object which is meant to aid contemplation and reflection.

Nostalgia

Nostalgia is defined as, ‘a sentimental longing or wistful affection for a period in the past,’ and is an established condition in our culture from music which evokes this feeling to fashion, television programs not to mention the general obsession with youth, youthfulness and youth culture. Struggling to stay the same or longing for a time passed all prevents the individual from being in the present the only real time.

The severing of links with the past and the view of tradition and the old as negative or as something which has to be destroyed or ignored in order to move forward is itself an act of self-sabotage like struggling in quick sand it attaches the attackers to what they profess to hate, which in turn gives rise to the phenomenon of nostalgia much like the actions of the revolutionary who smashes old statues creating more ruins for future generations to admire,

Damnatio memoriae is the Latin phrase

literally meaning condemnation of memory

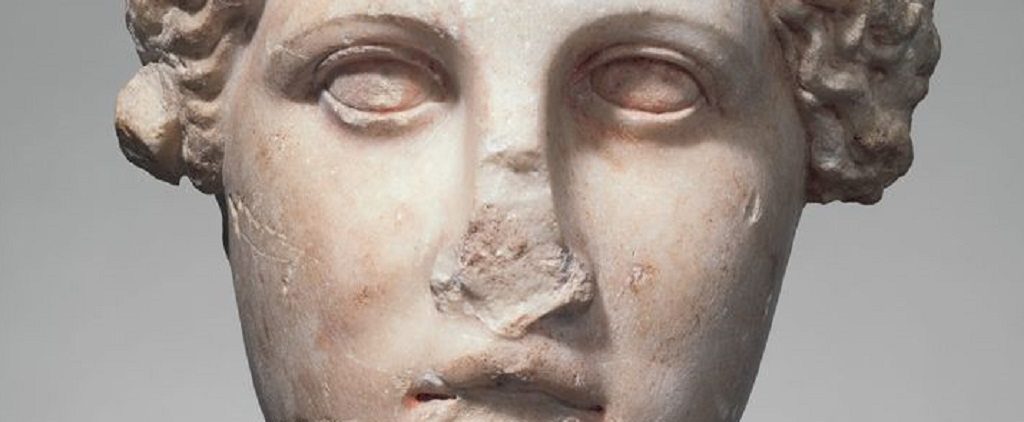

Defaced statue which its self becomes a sign of beautiful ruin.

Did the vandals who smashed Roman and Greek busts imagine that their actions would add to the ‘ruined aesthetic’ enjoyed by so many as an essential part of what makes the statues seem real, authentic? There actions had short term goals of course, they were embedded in their time acting out and reacting to the pressures around them the effects of their actions took centuries to acquire new cultural value. We though live in a time of great pace where the production of such values is immediate where we criss-cross from one useless posture to another. When we denigrate the past one moment or see it through rose tinted glasses the next we are trapped in kind of naive cycle,

“Our contemporary culture is indeed nostalgic; some parts of it–postmodern parts–are aware of the risks and lures of nostalgia, and seek to expose those through irony. Given irony’s conjunction of the said and the unsaid–in other words, its inability to free itself from the discourse it contests–there is no way for these cultural modes to escape a certain complicity, to separate themselves artificially from the culture of which they are a part. If our culture really is obsessed with remembering–and forgetting–as is suggested by the astounding growth of what Huyssen calls our “memorial culture” with its “relentless museummania,” then perhaps irony is one (though only one) of the means by which to create the necessary distance and perspective on that anti-amnesiac drive. Admittedly, there is little irony in most memorials, and next to none in most truly nostalgic re-constructions of the past–from Disney World’s Main Street, USA to those elaborate dramatized re-enactments of everything from the American Civil War to medieval jousts restaged in contemporary England,” Linda Hutcheon, ‘Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern’ 1998

In her essay Hutcheon highlights another branch of this inertia, irony, there is self-awareness in irony but its potential does not stretch to eliminating what it satirises or effecting change any more than watching a comedy panel show will change a political regime irony is in effect a way to do the same thing in a slightly different way.

Early Twentieth century avant-garde movements in the arts necessarily moved against stuffy institutions and refused to operate only in the established territory of the cannon but this gesture was not the same as smashing up an old masterpiece or statue (even if Marinetti wanted it to be) rather it was what was required to allow tradition or what is good in tradition, skill, discovery, exploration, the creation of meaning, to continue since the academies had decided to freeze culture and were effectively becoming museums of the present.

That problem today has been supplanted by the one discussed here irony and nostalgia are the ways now that things are kept the same in slightly different ways, ways which make us none the less slaves to an idea of the past or to a certain nonchalant attitude to the present, nostalgia is escapism and irony is self-delusion a way to do nothing with critical awareness.

Postmodern Stalling

Much of what is called avant-garde today gives force to these values attacks on ideas of taste and tradition are a bluff sustaining the illusion that avant-gardism is present in the work.

Money creates the market for objects that suggest a

link to a glamourous world and irony keeps

us from laughing it out of town

Jeff Koons ‘Balloon Dog’ 1992 (sold for 58 million dollars)

Koons talks about his work being generous, his choice of subject matter has allusions to pop art and he has also depicted himself in kitschy ways which then conceptualised by curators and collectors. Of course there is no generosity in pandering to the lowest common denominator, in glib sentimentality or in outright blatant consumerism.

The works are banal and decorative in the worst way, they thrive though and they do this not because they are moving people or challenging people or because they say something important about our society but because of money and irony, money creates the market for objects that suggest a link to a glamourous world and irony keeps us from laughing it out of town or shaming Koons for what he is a stock broker who saw an opportunity to exploit his culture for personal gain.

Koons is not responsible but only represents the type of art which comes out of a deadlocked culture hungry for escapism and affirmation a symptom of overall sickness.

Antidote

There are moments of real hope albeit they were crushed in different ways, the Bauhaus in Germany attempted to eliminate the hierarchical distinctions between art and craft and to unite creatives in a holistic approach to art which combined practicality and necessity with aesthetic principles and with philosophy and spirituality.

This was thwarted by the Nazi movement and after 1933 its proponents were scattered around the world to avoid persecution.

Romantic Marxism

In Britain the arts and crafts movement highlighted how art must form a part of the lives of ordinary people enriching and developing an awareness of aesthetics and beauty in the environments and in the activities of the poor while encouraging certain moral ideals,

“man at work, making something which he feels will exist because he is working at it and wills it, is exercising the energies of his mind and soul as well as of his body. Memory and imagination help him as he works. Not only his own thoughts, but the thoughts of the men of past ages guide his hands; and, as part of the human race, he creates. If we work thus we shall be men, and our days will be happy and eventful,” William Morris

This was never fully realised and was assimilated into a middle class sensibility where its effects were less revolutionary. Revisiting these projects and their values may be a way to reinvigorate the avant-garde of the early 20th century in ways loyal to the core values which made avant-gardism a word for credibility and revolutionary commitment,

“Romanticism took as its shared basis, Brazilian-French sociologist Michael Löwy notes, the fundamental critique of ‘the quantification of life, i.e. the total domination of (quantitative) exchange value, of the cold calculation of price and profit, and of the laws of the market, over the whole social fabric.’ Jeffery R. Webber, ‘E. P. Thompson’s Romantic Marxism’ https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/07/making-english-working-class-luddites-romanticism/

Romantic Marxism, is a term which describes a certain attitude one which combines revolutionary ideas with tradition Lowey uses William Morris as an example of this attitude,

“I love art, and I love history, but it is living art and living history that I love. It is in the interest of living art and living history that I oppose so-called restoration. What history can there be in a building bedaubed with ornament, which cannot at the best be anything but a hopeless and lifeless imitation of the hope and vigor of the earlier world?” William Morris

and as such these ideas may point to a healthier way forward for the arts and a new age of maturity where the energy and acting out of the new is creative not destructive and where this newness is clearly drawn from traditions not in spite of them an art world like this would not see the work of Koons thrive or the destruction of works of art or indeed a destructive nostalgia for the past,

“The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.” – William Morris

Natalie Andrews is an artist working with a range of mediums, she has shown her work at the Hoxton Arches in London and is currently working on a number of 3d works alongside painting exploring the links between painting and sculpture;

“I am interested in the way that we relate to one another and with space, how the environments we inhabit structure and dictate these relationships and create both opportunities for emancipation but also the deep alienation and separateness.”