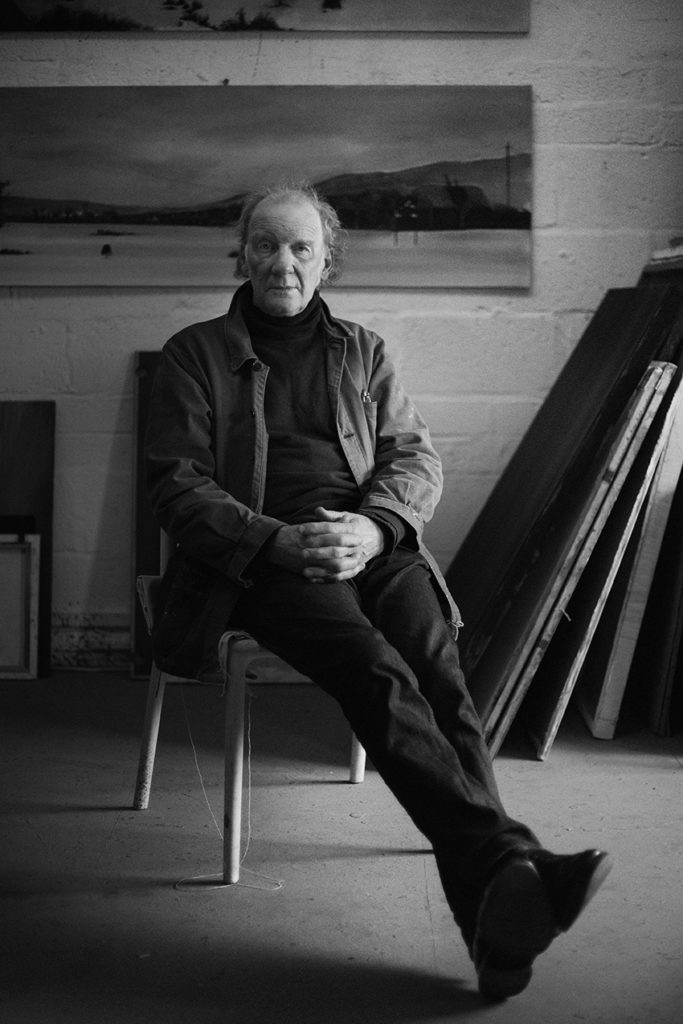

Jock McFadyen made a name for himself in the 1980s with his gritty portrayals of figures lurking on the streets of London’s East End. Over time, people disappeared from his paintings, giving way to expansive and often, desolate urban landscapes that seem to express a deeply psychological experience of place.

This February, the artist’s paintings of London alongside some more recent figurative works will be presented in a solo exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. Ahead of the opening, Millie Walton visited the artist’s studio in Bethnal Green to speak about his process, rambling around the city with Iain Sinclair and the death of the critic.

Do you tend to work more from photographs or memory?

Not entirely. I take photographs and then clip bits off and piece them together into the rough shape that I want, but [the photographs] are really only for architectural details. The number of windows, things like that. You can’t really sit on the edge of the A13 sketching as trucks go past. I used to go to Super Snaps, print out the photographs, look at them, see what I could use and then throw the rest away. So, I am using them, but it’s far from photorealism. I have to let the paint make the picture. Nowadays, I just use my phone because I don’t need good quality images.

Over the years, you’ve joined the writer Iain Sinclair on his walks, and your painting Tate Moss came from a kayaking trip…

Yes. That was controversial. Ian Sinclair goes walking everyday to get the cogs going for his writing and one day, when he was on one of these walks he came across hoarding along the towpath down towards Stratford, near Fish Island. This was when they were building the Olympic Park and they had put big blue hoarding all around as a sort of barrier. Anyway, he was walking alongside this hoarding and suddenly it went across the towpath making it into a cul-de-sac which angered the great pyschogeographer. So, he went to the photographer Steven Gill who he knew had an inflatable kayak. Then, Sinclair and I got into the kayak and entered the Olympic zone by water. We took photographs and paddled about like a couple of maniacs. There were all these blokes in hard hats and cranes. It was fascinating. The demolition was just beginning at that stage. That was around 2011, I suppose. Anyway, Sinclair made the mistake of writing about the experience in The Guardian or some other newspaper and the next time we went out in the kayak there was this big yellow floating barrier blocking our way. I have a photograph of it somewhere.

What do you think draws you to paint a particular building or landscape?

I haven’t got a clue. Just a nice shape or interesting shadow. I sort of don’t want to know or to analyse it, but it is something I’ve been asked about before and I’ve always answered in a similarly obtuse way. It might even be as gratuitous as ‘Ah I could get a good picture out of that.’ I don’t mind admitting that because it’s like a springboard: once the painting takes over, it doesn’t matter. So, if it’s random and inconsequential, all the better.

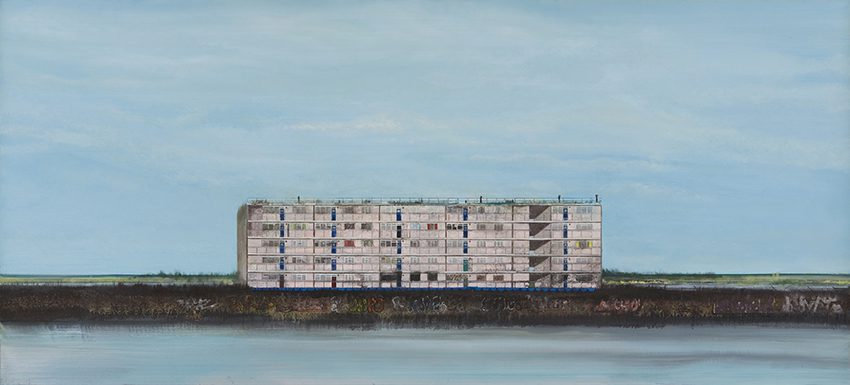

A lot of your landscapes have a kind of desolate quality.

When someone like Iain Sinclair looks down on six lanes of traffic, I think he sees through all of that to the landscape beneath. Similarly, if I imagine the M6 after a nuclear war with all those empty filling stations – that’s a really compelling image to me. But also on a more banal level, if you want to get a picture right in the formal sense, you don’t want people in the way. You either have to look through them or wait for them to move out of the way. It’s the opposite of tourists who take selfies with London landmarks. I was taught by abstract painters and that’s all about the paint, the grid and depth of field. I quite like that stringency, ensuring that the pictures work formally.

You started off by painting people. What inspired the shift away from figuration?

I paint instinctively and it took me a long time to realise what any advertisement would’ve been able to tell me instantly, which is that when you include a figure in an image everything else becomes secondary, the figure is the protagonist.

I used to see somebody in the street and I’d try and capture them, but I would spend weeks getting the formal arrangement of the location right. However, when people looked at the works, they just saw the figure and they wouldn’t question or consider all of the details that I had agonised over. So, the figures gradually became smaller and then in 1991, I designed the set for a ballet at the Royal Opera House. I didn’t have to put any people in the set because there were the dancers. After that, when I went back to my own paintings, I realised I had actually been painting places the whole time, but from a different point of view.

When you’re making a painting, does the image have to have a connection to the present moment or can you work from experiences you’ve had in the past?

If you don’t do what say Lucian Freud did which was to get someone to sit in front of him and work from life, the figure in the picture is always going to be something between portraiture and fiction, it’s going to be at least partly invented. I suppose that’s how I see the figures I paint: they’re a mixture of different people I’ve seen and I transport them into a new place.

I think a landscape painting is always, to some extent, a manipulation of a landscape. If you think about the 17th century Dutch landscapes, they’re all basically fictional because the landscape is actually flat but they wanted rocky landscapes just like here in the UK we might want the Californian sunshine. When people used to go to Rome and paint the ruins, they would just do a pillar and a bit of a Renaissance landscape. I guess what I’m saying is that nothing is pure and I make decisions based on what makes a better picture, which might mean moving a tree, for example.

Has painting always been your preferred medium?

When I was a student, I used to make films with Jacob Rees-Mogg’s aunt Anne Reess-Mogg who was one of my best friends and nothing like her nephew who was a child in those days. She was a well-known avant-garde filmmaker. This was before Channel 4 democratised filmmaking in 1982 and millions of production companies sprang up because Channel 4 never made their own films, they just commissioned them. But then, painting, took over for me and I gave my 16mm camera away to the Film-makers’ Co-op and never looked back, but I still love films and I put film ideas into my paintings.

How do you think the London art scene has changed over the course of your career?

People like me, old artists who’ve been in London their entire career, think about that question a lot. When I was a student at Chelsea College of Arts in 1970s, what everyone desperately wanted was a three week show on Cork Street in one of the posh art galleries. You just about sold your mother to get a solo exhibition on Cork Street. It was all we dreamed about. We didn’t dare dream of having a banner over the Tate saying Jock McFadyen in bright red letters, that was too much, it still is! So, three weeks on Cork Street was the aim.

Then, sometime in the 90s, art fairs took over. It was around the same time the YBAs emerged, which was after the recession. The YBAs were like punk after the sort of middle of the road rock that been mulling around for years and that was fantastic, but there was another generation of artists who would sell their granny for three days at Art Basel Miami Beach or the Armory Show in New York. Three days at one of those fairs became more important than the one man show on Cork Street. At the same time, group exhibitions became more important than solo exhibitions because you were being curated. It was the rise of the curator over the dealer.

That changed again in the late 90s when what everyone wanted was two or three hours on a Thursday evening at Sotheby’s. Now, it’s NFTs on your phone and Sotheby’s are really elbowing everything aside to get into NFTs because they’ve stolen a lot of business from the retailers and galleries. Galleries have gone completely high end and what I would call the middle class galleries have all gone because they can’t sustain. There are really huge, mega galleries like Gagosian which has more retail space internationally than Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Tate St. Ives and Tate Liverpool put together. It’s really just a shop and they can’t actually afford to sell a picture that’s worth less than say 5 million. The auction houses have made that market.

I was talking to the director of a well-known London gallery a couple of years ago who said, ‘I’m fed up of sitting here waiting for some dentist from Finchley who’s had a good lunch to wander in and buy something.’ And the truth is that if dealers don’t do the international art fairs, they’ve had it. [The art world] is completely driven by money. We used to have a critical backdrop. As an artist, you were frightened of the critics because they were clever and analytical and now they’ve become much more journalistic. It’s all about what’s hot and what’s not. Work that sells for millions is taken more seriously and there’s very little middle ground. I’d say up to about £10,000 the market is quite healthy but the market between £10,000 and £100,000 is quite small. Then, the market above a million is fine because it’s like Canary Wharf and the traders.

Has the affected how you feel about your place within the art world?

The majority of artists, myself included, have never sold a painting above say £250,000. It’s just a small number of artists who are selling in the millions and it is a controlled market with guaranteed sales. The people buying want to pay more. They don’t want to pay less because their stock will go down if an artwork was sold for less.

[Pointing at a large-scale painting behind him]. Who’s going to want to buy that? You’d have to be someone who’s able to pay me £70,000 and who also has the space to hang it. There are people like that: people in publishing or music, but they’re not really the art market.

Does that parallel observations you’ve made of London itself and how the city is changing?

There is a parallel because if there was no money, there would be no glass towers around Liverpool Street and no Renzo Piano building in London Bridge. When the trade towers were hit, it seemed to me to be fantastically obvious symbolism. The trade towers were really just a way of expressing power and money. Big dick architecture.

Your show at the Royal Academy is titled Tourist without a Guidebook. How did that name come about?

The critic Tom Lubbock who died some years ago wrote the catalogue for my 1991 exhibition at the Imperial War Museums which was about the dismantling of the Berlin Wall. In the text, he wrote that Jock Macfayden is like ‘a sightseer without a guidebook.’ I’d had a conservation with him similar to this one about wandering around and what attracts me towards something. When he wrote that, I thought that’s exactly right: I want to be neutral. In my view, that’s the perfect position for an artist. So, I decided to use that title for this exhibition, which is the last of a series of four.

How did you select which works to include?

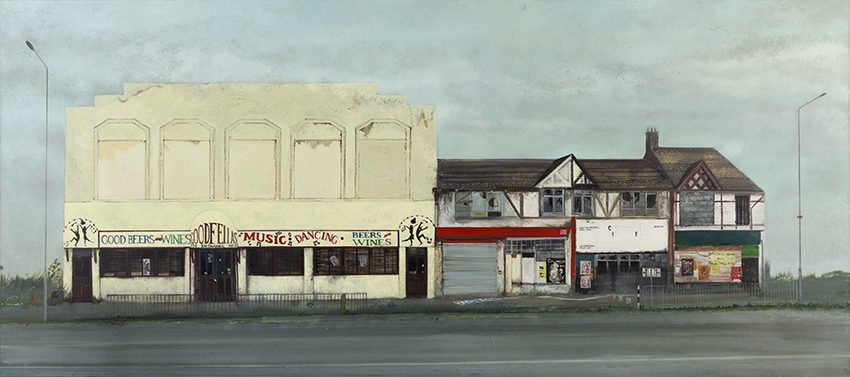

The exhibition is on at the same time as the Francis Bacon show, but it’s a free display and all the pictures are of London, which was decided by consensus with the curators. There will be quite a lot of large paintings, which I haven’t shown before or sold. We haven’t borrowed any works.

I think we’ve put together an exhibition which makes sense in terms of how my work has evolved. For example, I’ve got this painting of a nightclub in Dagenham called Goodfellas, which I made twenty years ago and then, a few years ago, I started making these pictures that seemed to be in a nightclub and I realised that I was, in a way, painting the people that might have gone to that nightclub. Some of those paintings will also be included in the show.

“Jock McFadyen: Tourist without a Guidebook” runs from 5 February to 10 April 2022 in the Weston Rooms of the Royal Academy of Arts. For more information, visit: royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/jock-mcfadyen

Featured image: Jock McFadyen in his East London studio. Photograph by James Houston @jameswilliamhouston

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.