[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]hen you occupy—a city square, or a factory, for example—you simultaneously inhabit both space and time.

This is a constant and universal property of occupations. The space chosen to occupy usually has symbolic currency. The longer the space is occupied, the more political currency is earned by the occupiers. The global Occupy movement, because of its cellular, networked nature, was able to simultaneously occupy multiple spaces at the same time. US art historian and political activist Yates McKee (2017, p. 14) refers to Occupy as “an event that involved a historic conjunction of contemporary art and radical politics.” He notes that artists were not only integral to the movement (as activists); they influenced it aesthetically so that non-artist activists became concerned with aesthetics, performance and poetry. He claims that:

Art and artists were essential to the core of the movement itself as initiators and organizers, rather than secondary decorators adding their work onto a social movement that could have otherwise existed without them. (2017, p. 17)

Occupy might have been “a historic conjuncture” of art and protest, but it certainly was not the first. Indeed, artists have played key roles in occupations for at least the last 50 years. In the UK perhaps the most famous example is the artist-occupation of Hornsey Art School in 1968. Copycat sit-ins occurred at several other UK art schools in sympathy and solidarity. In the same year, the Situationist International (SI) famously played a key role in the occupation of the Sorbonne and the Nanterre universities in Paris. Situationist graffiti, slogans and posters became icons of what turned into a global May ’68. As with Occupy in September 2011, the spirit of May ’68 ushered in simultaneous occupations across a multitude of spaces across the globe. The SI was part of an avant-garde tradition that aimed to merge art and life. Such avant-garde artists did not merely illustrate occupations: they were also key organisers. They laid the foundations for new forms of political art and the aesthetically infused Occupy movement.

From Les Enragés to Los Indignados

At the time of the 1968 occupations, the Situationist René Viénet published Enragés and Situationists in the Occupations Movement. It is striking that the French word enragés is in some ways reminiscent of the Spanish word indignados (enragés and indignados: the outraged and the indignant). Could the etymologies of these words reveal links between two occupation movements from very different times and space? The etymology of ‘indignant’ contains a moral element. It literally translates from the Latin as ‘not worthy’. This is consistent with the contemporary Spanish usage, since the Indignados movement regarded themselves as having been unfairly treated (they were ‘not worthy’ of their maltreatment). The term might be associated with being aggrieved, angry and resentful. Indignant in French is indigné, but it could also be translated as outré. This etymology can be traced to the Latin term ultra, meaning beyond, but the term has clearly evolved since then, through the Old French term ou(l)trage into English. ‘Outrage’ retains something of the Latin if it is considered to refer to crossing (beyond) a reasonable boundary. There is therefore a spatial element to the term: when somebody crosses a reasonable line (committing an outrage) you might feel indignant (that they have treated you unfairly). Feelings of indignation and outrage may have subtly different meanings, but in contemporary usage they are hardly a million miles apart: they appear as synonyms on the word processor used to type this essay, for example. Both the Enragés of 1968 and the Indignados of the early 21st century felt enraged (or indignant) towards the ruling elites and the political system.

Situationist graffiti, slogans and posters became icons of what turned into a global May ’68

Les Enragés was a term applied to far-left agitators during the French Revolution; it was also applied to the left-wing agitators in Parisian universities in the build-up to 1968 that induced “demonstrations, expulsions, and then several days of street fighting (in which all the French situationists [took] part)” (Knabb 2011). In fact, the Enragés formed “during a struggle against police presence in Nanterre preceding the unrest in Paris” (Viénet 2014).

The Indignados movement was born in reaction to the high unemployment, economic crisis and heavy cuts resulting from the global banking crisis of 2008. It started by using social networking and other online platforms to facilitate large numbers of participants: somewhere between 6 and 8.5 million Spaniards are estimated to have taken part in its demonstrations (RTVE 2011). They called themselves ‘Los Indignados’ after Stéphane Hessel’s book Time for Outrage!, which was translated into Spanish as ¡Indignados! (Gerbaudo 2011).

Clearly, there are historical and geographical differences between the beginnings of these two movements, but there is evidence to support a claim that both were born from outrage.

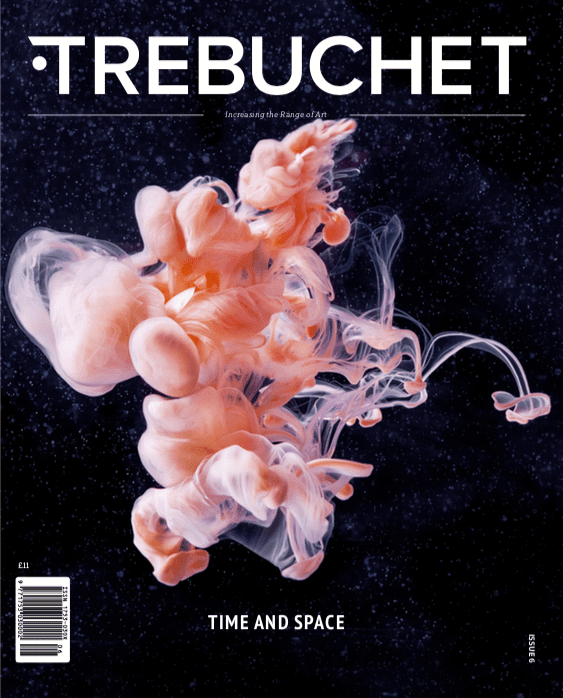

Continued in print. Read more in Trebuchet 6 – Time and Space

Sources

Badiou, A 2012, The rebirth of History: times of riots and uprisings, Verso, New York

Bitter lake 2015, BBC

Bourriaud, N 2002, Relational aesthetics, Les Presse du Réel, Dijon.

Fisher, M 2009, Capitalist realism: is there no alternative?, Zero Books, Ropley.

Fowkes, M and Fowkes, R 2012, ‘#Occupy Art’, Art Monthly, 359, pp. 11–14.

Gerbaudo, P 2011, ‘Los indignados: the emerging politics of outrage’, Red Pepper, 27 August, viewed 6 June 2018, <https://www.redpepper.org.uk/los-indignados>.

Harvey, D 2012, Rebel cities: from the right to the city to the urban revolution, Verso, London.

Holloway, J 2012, ‘Afterword: rage against the rule of money’, in: F Campagna. & E Campiglio (eds), What we are fighting for, Pluto Press, London, pp. 199–205.

Holmes, B 2012, ‘Eventwork: the fourfold matrix of contemporary social movements’, in: N Thompson (ed.), Living as form: socially engaged art from 1991-2011, MIT Press, New York, pp. 72–85.

Knabb, K 2011, ‘The Situationists and the occupation movements: 1968/2011‘, Bureau of Public Secrets, viewed 2 February 2017, <http://www.bopsecrets.org/recent/situationists-occupations.htm>.

Loewe, S 2015, ‘When protest becomes art: the contradictory transformations of the occupy movement at Documenta 13 and Berlin Biennale 7’, FIELD: a journal of socially engaged art criticism, 1, pp. 185–203.

Mason, P 2012, Does Occupy signal the death of contemporary art?, BBC, 30 April, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-17872666>.

McKee, Y 2016, ‘Occupy and the end of socially engaged art’, e-flux, 72, April, viewed 26 January 2018, <http://www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60504/occupy-and-the-end-of-socially-engaged-art>.

McKee, Y 2017, Strike Art: contemporary art and the post-Occupy condition, Verso, New York.

Nietzsche, FW 2003, Beyond good and evil: prelude to a philosophy of the future, Penguin Classics, London.

RTVE (2011) Más de seis millones de españoles han participado en el Movimiento 15M, viewed 19 February 2017, <http://www.rtve.es/noticias/20110806/mas-seis-millones-espanoles-han-participado-movimiento-15m/452598.shtml>.

Sloterdijk, P 2010, Rage and time: a psychopolitical investigation. Columbia University Press, New York.

Viénet, R 2014, Enragés and Situationists in the occupation movement, Collaboratory for Digital Discourse and Culture, viewed 4 June 2018, <http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/enrages.html>.

Žižek, S 2012, The year of dreaming dangerously, Verso, London.

Martin Lang is a lecturer in Fine Art at the University of Lincoln. He is a member of the Politicized Practice Research Group (Loughborough) and part of an Art Activism and Political Violence community of interest group. Prior to working at Lincoln, he taught on the BA Fine Art and BA History & Philosophy of Art programmes at the University of Kent and on the Foundation Diploma at University for the Creative Arts. He has published research on militancy, the neo-avant-garde and the apocalypse and revolution.