[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he story of Orpheus and Eurydice has found particular resonance with those who, like Orpheus himself, act on the recognition of their experiences: artists.

From Rilke to Jean Cocteau, Arcade Fire to Monteverdi, Titian to Cy Twombly, their work has echoed the myth and the myth has echoed their work.

It is a myth that drips with art, its story centering around the potency of music, poetry and the image. Accordingly, these three components are what comprise the project Orpheus and Eurydice, the first performance of which was on Saturday 10th January at Ugly Duck, 47/49 Tanner Street in London Bridge. A collaboration between Tom de Freston, Max Barton and Kiran Millwood Hargrave, the evening was curated by Freston and produced by Chris Edis, in a first incarnation of a wider project.

The evening had visual and auditory elements: the later performance of poetry and song was preceded by an exhibition. Tom de Freston, the project’s curator, had filled the planked and airy studio space with his characteristically large, spatial paintings. So the event began with a visual layer, lining the eye with the ambiguity and suggestiveness only images are utterly capable of.

The space which Freston’s work most explored here was the Underworld, an important place in the myth; it is where Orpheus travels with his music to bargain for his dead lover Eurydice’s release back into the world of the living.

Their journey out of the Underworld, she following him, contains the tragic moment on which the most prominent version of the story hinges, when he looks back, checking she is there, and going against the terms of his Hadean bargain. At his look, she vanishes forever.

The Underworld is a locating analogy for death, a place that will always be relevant to us mortals, modern or ancient. Death is necessarily unimaginable, and yet it is so frequently imagined – in art and religion – perhaps for that very reason. Like Orpheus, knowing you can’t look doesn’t stop you from looking.

In Freston’s hands, the Underworld is an anonymous, windowed space, with signifiers of the familiar – light bulbs, staircases and fireplaces – that still feels unsettling and placeless. After walking round the fifteen paintings completed for the project so far, it feels as though you have looked at the same desolate concept of a room, not an actual room, from more angles than your brain can compute.

This viewing experience performs the project’s overall purpose, in expressing something honest and modern about how simultaneously blurred and clear the truth of a story is to us. There are elements of confusion and of clarity in this strange and knowing tale of two lovers, and that combination is the very reason for its continued effect.

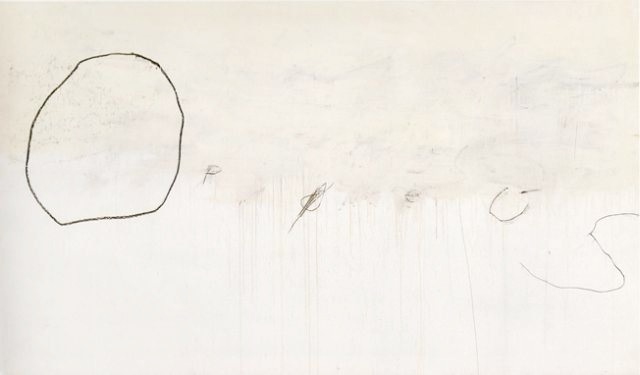

For example, Twombly’s own explicit and also elusive painting (right) uses letters to make words and images, the ‘eu’ perhaps alluding to and retrieving ‘Eurydice’, and the ‘O’ of ‘Orpheus’ forming a yawning circle that stands out in the mist of paint.  His paintings reach for the lost, and indeed circular, ideas surrounding myth through time and space. This use of words and images in Cy Twombly, Orpheus (1979) ekphrastic, just like the playful and subtle conflation of textual sources and creations which Tom de Freston and his collaborators Kiran Millwood Hargrave and Max Barton produce in their multidisciplinary telling.

His paintings reach for the lost, and indeed circular, ideas surrounding myth through time and space. This use of words and images in Cy Twombly, Orpheus (1979) ekphrastic, just like the playful and subtle conflation of textual sources and creations which Tom de Freston and his collaborators Kiran Millwood Hargrave and Max Barton produce in their multidisciplinary telling.

As Freston puts it: “Primary to this is the model of painting as a myth generator rather than merely a mode of visualisation and description. Ekphrasis becomes both a means and a metaphor of this generative creativity, resulting in an immersive narrative experience that is far more myriad and manifold than conventional forms of retelling. And what is true of painting can be true of all the disciplines and mediums at work: they can each reflect the surrounding story; comment upon it; and re-generate it in unexpected or forgotten ways.”

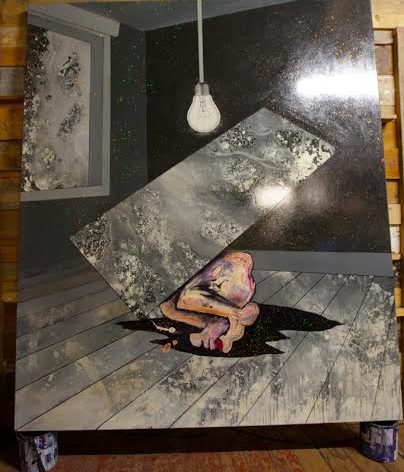

‘Francesca Woodman as Eurydice I’ (2014)

200x170cm, oil on canvas

A highlight of Freston’s work for me was a painting called ‘Francesca Woodman as Eurydice I’, which shows a rectangular slice of what could be sky or earth, mirror or matter, toppling at an angle onto an obscured or crouching figure. A large light bulb hangs obtrusive and demanding, shining electric light onto whatever the old, forgotten dark is hiding.

A talking point of the artwork was the glittered varnish that glossed each painting. The glitter draws attention to the surface, literally and metaphorically, its immediate decorative aspect only strengthening the sense of artifice, the discomfort of the work.

As the crowd mingled and looked, the space was turned into a theatre around them, chairs brought in amidst the paintings. We took our seats, then the lights went out. Those images faded into nothing, on the edge of vision only if you blinked. In this darkness, the room’s form became as ambiguous as the painted one.

One by one, the musicians – led by Max Barton, with accompaniment by James Turnbull and Ensemble Perpetuo, with Chris Barton on double bass and Nick Tugg on drums – turned on small individual lights. The performers glowed, and a few nearby paintings rose out from the surrounding gloom, even more suggestive than before.

The shift in focus from one sense to another, from eye to ear, heightened the first low hum that accompanied the poet Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s opening lines of verse.

For the next half an hour music and poetry weaved in and out of each other in a richly discursive mesh of words and sounds, sometimes obscuring and at other times refining each other. Much like in the din of time, with its obfuscations and deceptions, the lyrical narrative of the poetry glimmered through the gravelly textures of Max Barton’s band, and their gypsy jazz-esque stylings.

“Why is it that the accordion lends itself to all things deviant and hellish?” a friend commented afterwards. Whatever the reason, the music definitely brought the room down into the deep with their darkly comic musical swaying, which at points was reminiscent of Tom Waits and appropriately the Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ album The Lyre of Orpheus. Barton’s own songwriting was at turns bluesy and sombre, then discordantly, joyfully carnivalesque. He also managed to pull the instrumental components together as a cohesive whole, creating a richly textural soundscape.

Millwood Hargrave’s poetry was a real strength of the performance, the writing containing an awareness of its literary context, acknowledging and playing on this deftly, never labouring the point. The voice of the poems (mostly Eurydice, with some choral poems) had a directness that at points was striking and beautiful. She shortened the protagonists’ names to ‘o’ and ‘e’, turning Orpheus and Eurydice into modern shorthand, ciphers for sound even, as highlighted vowels that resounded through the poems.

The most memorable poem was ‘Host’, in which swans nest beneath Eurydice’s scalp, leaving her ‘brain full of eggs’. The images stuck afterwards, and the vividness of natural imagery brought back Ovid’s Metamorphoses, to the point where I confused one with the other until I looked them up.

In Book XI, Ovid similarly describes nature’s relationship with the mythical characters, here in grief:

“The trees that often gathered to your song, shedding their leaves, mourned you with bared crowns” (A. S. Kline’s translation)

‘Like light,/it is only at a distance/this place holds any shape’

from the poem Sapling seems to shine with the ‘light’ motifs in the paintings, positing the idea of the particular clarity the myth takes on from the viewpoint of today, so distant from its origin.

‘lets start with the sky yes the sky the sky’ are the words which open the sequence of poems which Millwood Hargrave performed from memory, and comes full circle with the closing lines: ‘…dark god never lies e drops o rises to a once started sky’. That final line is a perfect encapsulation of the entire experience, as the night sky of the room we were sitting in, sometimes glittering with passing planes and trains, the slices of painted skies in Freston’s paintings, and the repeated word ‘sky’ contained in the poetry slid alongside one another in layers.

As the project’s proposal says: “All of music was said to be held in Orpheus’ first note, and in his first word all of poetry. Might this be mirrored by a body of paintings that refract back the history of the medium?”

The event on the 10th January was a self-confessed work in progress, with some exciting plans to come. The collaborators intend to evolve what exists into several further outcomes: a more elaborate piece of immersive theatre, again uniting songs, poetry and painting, a graphic fiction by Tom de Freston, weaving the songs and poems into the fabric of the visual Underworld, and an online digital platform built by the animator Leo Crane.

This online version will house an interactive array of song and poetry recordings, films of past performances and the paintings and fragments from the graphic novel. Whatever the eventual outcome, for me the project’s strength lies in its exposition of process. In both its content and its method it positions itself alongside the myth, in the processing in-between-place of the perpetual present.

As the evening’s event finished, I walked through the space to leave, past fingers pointing at paint and people leaning towards each other, testing out their interpretations in words. I could feel the myth puzzling its way into the January evening of early 2015. The image of Orpheus and Eurydice ascending from the place of death seemed suddenly so apt, as that ancient myth struggled its way to the light, refigured as sure-footed in its ambiguities and forward-looking in its fragments, in the light of this new project.

Split from the same root,

we are a forest night

without margin, stretching

from dark to star to dark

under a scrambling moon.

Dear one, see how the fish

shine below us, like mirrors.

from ‘Night Tides’, by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Photos: Erol Birsen

Heat with our garlic. Salt to taste.