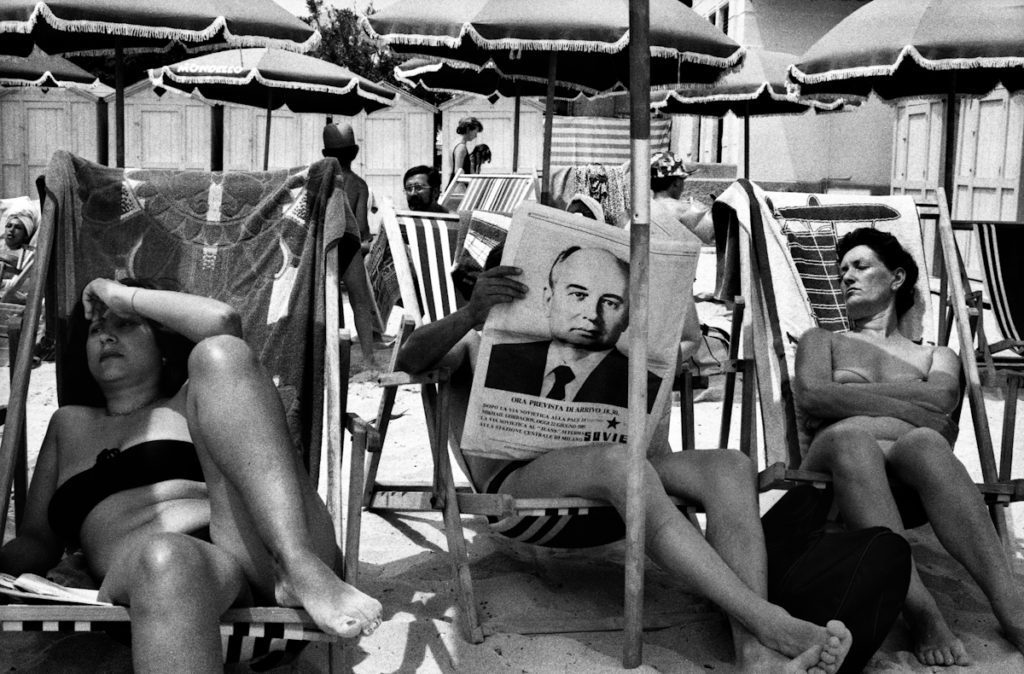

Photographs have a complex relationship with reality. Richard Avedon once said ‘all photos are accurate but none of them is the truth’, in all likelihood he had a particular form of photography in mind as opposed to photoshop, airbrushing or superimposition. But his essential point is that while the details of a photograph were really there, in a place, at a time, the context that paints a person as a hero or villain is often obscured or fabricated by the composition of the shot. Rather than question the truth of ‘photography’ Palermo Mon Amour presents a more nuanced view of social history, doubly experienced through the photographer’s vision of events and the curators choices in placing the works in specific ways that create connections. We are shown a history but of what?

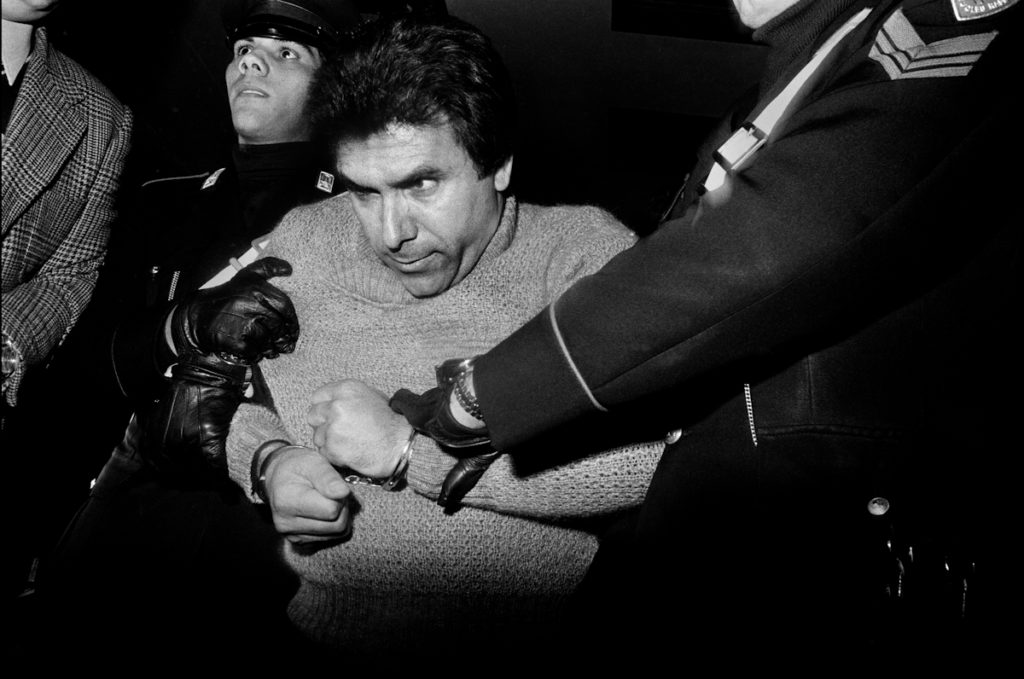

The history of post-war Palermo is one of economic neglect, mafia influence and violence but also hope. Covering the period from the 1950’s to the 90s the documentary style of the five photographers connect the eras through the emotions on the faces of the local people. In the photo the resilient character of these people comes through. A toughness and earthy closeness to real life captured against the backdrop of a city that often looks either like a building or bomb site, amongst which both photographers and subjects find their lives.

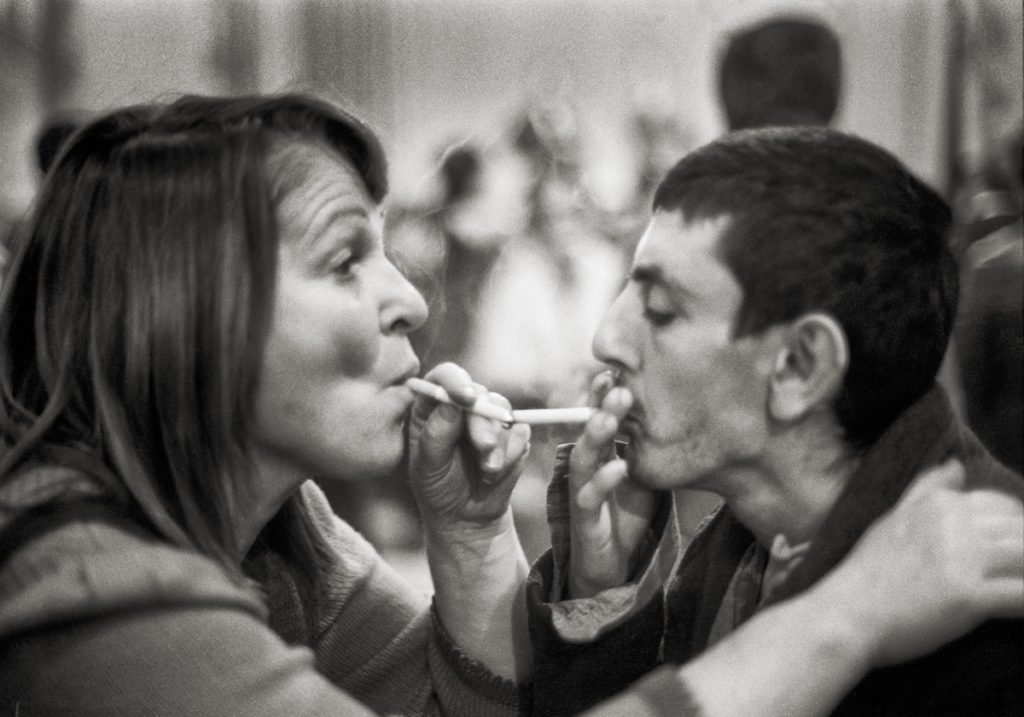

Enzo Sellerio’s (1924-2012) pictures in particular capture the elation within the restoration era of post-war Palermo. Faces in motion, smiling, amongst other faces finding community in moments amongst a modernity trying to put itself together. His pictures capture the pleasures of squalls of Sicilian youths gambolling around a car, or collapsed into the grimy transcendence of the adolescent night. His relationship with Sicily ran particularly deep, as an educator, publisher, and local chronicler he devoted his life to celebrating the persistence of optimistic lives limited by hard circumstances.

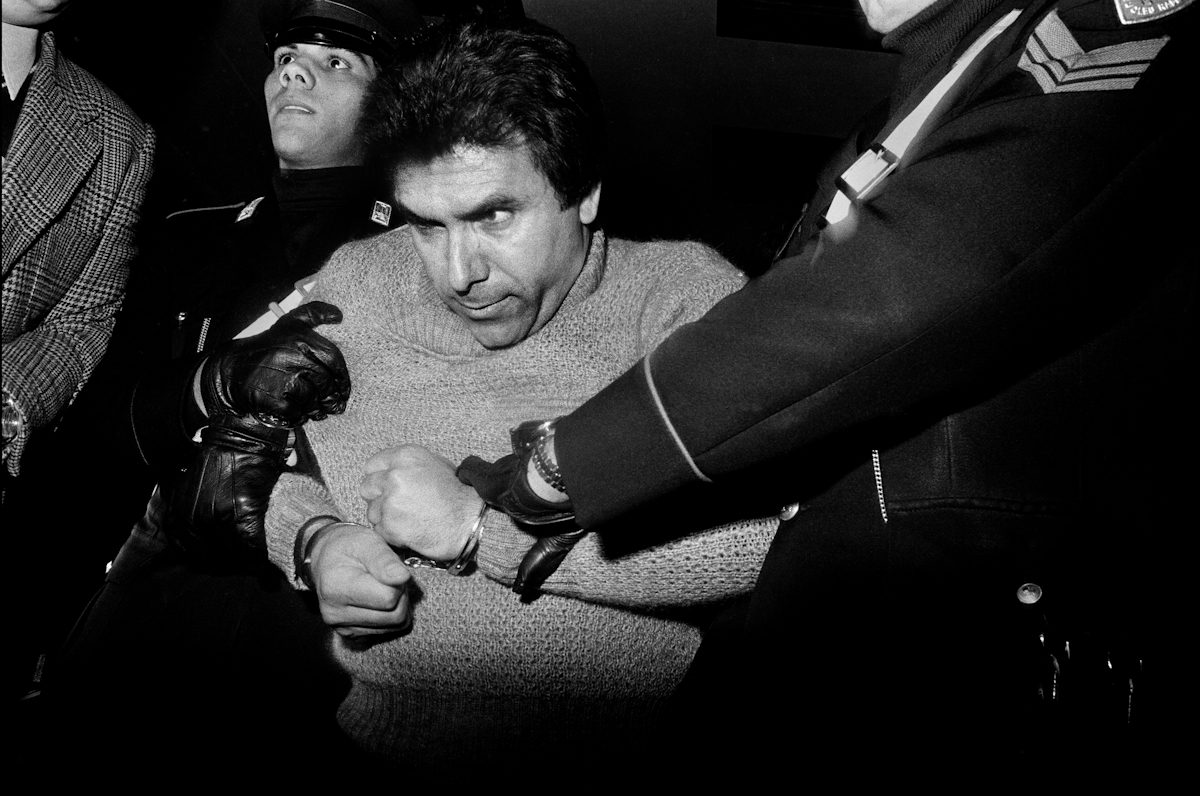

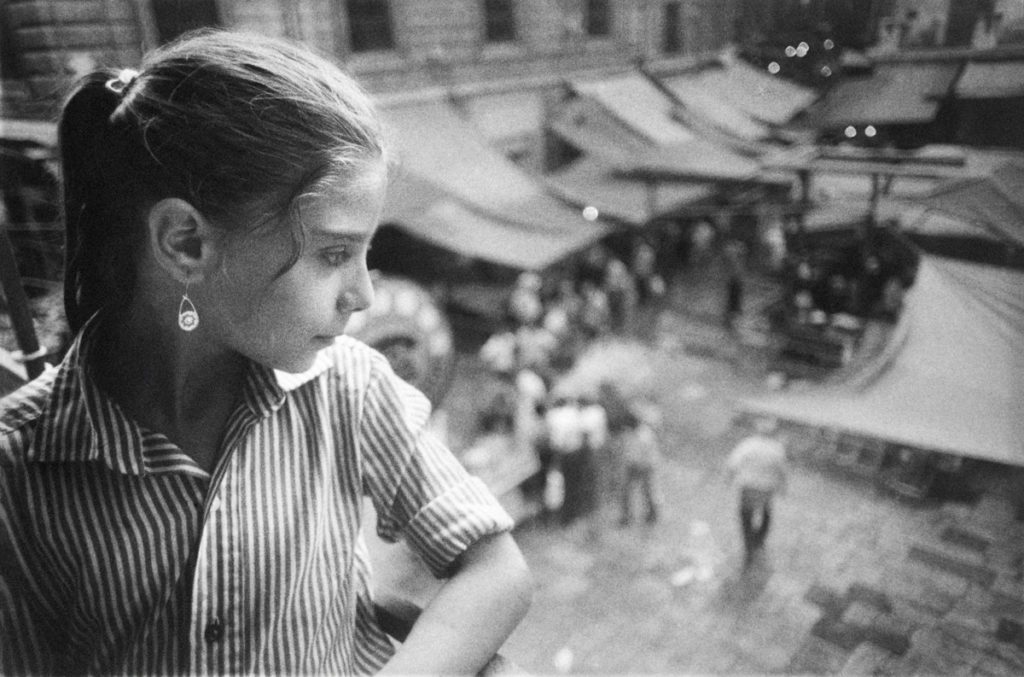

If Sellerio’s work captures the earthy dreams of a society emerging from the darkness of the Second World War then the photos of Letizia Battaglia (1935-2022) are an expression of unwavering judgement tinged with rage. The layout of the Battaglia’s work mixes more social aspects of Sicilian life alongside shots of murder and destruction imparting the aura of a community either holding its breath waiting for release, or actively choking. The pensive girl looking from a balcony doesn’t seem to survey a glittering horizon so much as remain contained, the set of her smile taut, the witness of her gaze purposely unseeing.

It would be easy to say that the decades progressed through each photographer, each forming a line before the other from the 50s straight to the 90s, each vision closing seamlessly around the opening of the next, and the entire exhibition packaged up a neat explanation of time, crime and moral outcomes. However, walking through the viewing halls of the Fondazione Merz, the overall vision is more nuanced. Decades overlap, and the variety within the photographers work shows how their relationship to Palermo, whether personally or within a series, carries the city’s story in emotive ways; and pulling material from factual and mythological sources give an operatic twist to history. Photography makes heroes of people and places and villains of the viewer. We steal our kisses, glances and poetic words, and fashion the worlds we want to inhabit.

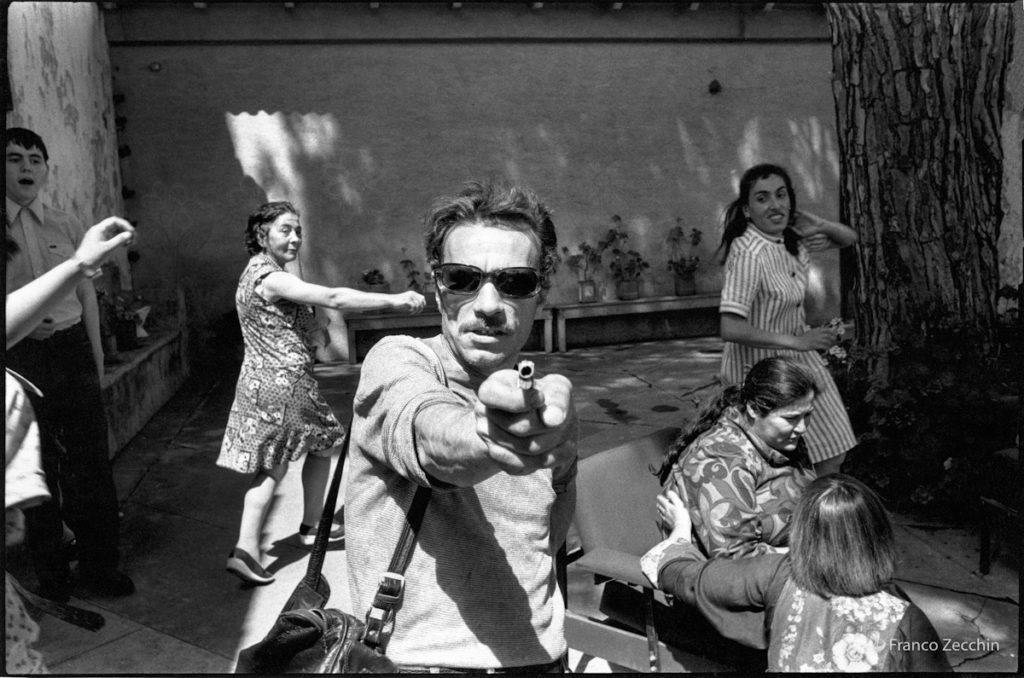

Unlike painting, photography contains real people and real lives, Franco Zecchin’s (b.1953) work for example has been praised for how he uses character, images and illusions to reveals empathetic archetypes, story tropes from around the world that describe the features of survival, redolent of the human race. Commonalities that, while specifically drawn, connect us. Included in the exhibition is his work with psychiatric inmates where their portrayal takes on a theatrical aspect, faces exaggerated into classical dramatic shapes, but solid in their worlds.

Is this the essential truth of the exhibition? That in the end there is only humanity and the pain and deaths of individuals become flotsam and jetsam in the sweep and suck of historical tides? In some sense it depends on proximity, knowledge and experience. If you recognise the people, events or periods in these images then clearly the works will tell a different story. Indeed, while it’s not impossible to view the exhibition from an purely aesthetic ahistorical perspective, it is very difficult not to be drawn into the action surrounding any of the pictures, the links to the era and larger social contexts.

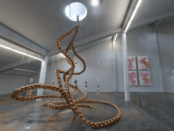

As Avedon suggests, in any given photo we’re given compelling detail which carries an accuracy of experience (people watching a dead body), but not a truth of causation, or how the events sit within a timeline of facts (is it tragic? Who was the deceased to the onlookers?). And while we don’t necessarily have a timeline of connected facts, the curator Valentina Greco gives us an associative timeline of Palermo, subjective yes, but convincing and rich with the resonant fervour of Arte Povera and its proponent Mario Merz (1925-2003).

Recollecting the tenants of Arte Povera where the immediacy of everyday objects, even the human body and behaviours, without transformation could bridge the natural and the artificial and become art. We can impose upon these candid testaments of life in Palermo as being just those unalloyed statements of art that Mario Merz himself might have appreciated. It is a potent idea that unlike other readymades which transformed the everyday materials, such as manufactured items, into disembodied vessels for the corporate art consciousness, Arte Povera sought to maintain the integrity of the primary material. And by bringing the viewer into the material space rather than the other way gives an strength to the world as it is. We are shown these images and rather than being polished into this or that rhetorical stance are presented as they are within a pregnant context. In this way the depicted era has an independent life and speaks to us across the years in ways that we recognise.

Against the grain of commercial art, the endless trumpeting of investment over meaning, of artworks overwritten with academic meaning or pretty but dumb identity works, the clarity of these photographs and their setting within this exhibition feels urgent. Artspeak has its place but the blatant nature of the exhibition (blatancy?) feels more visceral and exciting than a coded invitation to your own mind. The power and vitriol of these images, ripe for ironic parody, disenchantment, and commercial distance, is rewarding because of that vulnerability. They stand against the posed frame of art as commodity, fetishised through analysis, and packaged as decoration. Now more than ever we need exhibitions that change us by the direct approach.

—

Palermo Mon Amour. Enzo Sellerio, Letizia Battaglia, Franco Zecchin, Fabio Sgroi, Lia Pasqualino

17 April to 24 September 2023 – curated by Valentina Greco in collaboration with the Centro Internazionale di Fotografia Letizia Battaglia.

Fondazione Merz, via Limone 24, 10141 Turin, Italy

Travel for this article supported by Sutton

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle