[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]arents’ praise predicts attitudes toward challenge 5 years later.

Parents’ praise , childhood nectar or poison?

Must. please. father. must. appease. mother. my. sibling. my. enemy. the. world. so. cold. so. hostile. so. cold. so. cold.

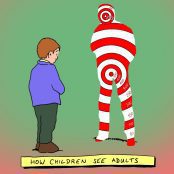

Toddlers whose parents praised their efforts more than they praised them as individuals had a more positive approach to challenges five years later. That’s the finding of a new longitudinal study that also found gender differences in the kind of praise that parents offer their children.

The study, by researchers at the University of Chicago and Stanford University, appears in the journal Child Development.

“Previous studies have looked at this issue among older students,” according to Elizabeth A. Gunderson, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Temple University; Gunderson was at the University of Chicago when she led the study. “This study suggests that improving the quality of parents’ praise in the toddler years may help children develop the belief that people can change and that challenging tasks provide opportunities to learn.”

Parents praise their children in a variety of ways. They might say, “You worked really hard” after completing a challenging task or “You’re a very smart girl.” Or they might offer general comments such as “Great” or “You got it.” While all of these phrases sound positive, prior research has shown that they have different effects.

Process praise, when parents praise the effort children make, leads children to be more persistent and perform better on challenging tasks, while person praise (praising the individual) leads children to be less persistent and perform worse on such tasks. This is because process praise sends the message that effort and actions are the sources of success, leading children to believe they can improve their performance through hard work. Person praise sends the opposite message—that the child’s ability is fixed.

Researchers in this study videotaped more than fifty 1- to 3-year-olds and their parents during everyday interactions at home (the families represented a variety of races, ethnicities, and income levels). Each family was taped three times, when children were 1, 2, and 3. From the tapes, researchers identified instances in which parents praised their children and classified that praise as process praise (emphasizing effort, strategies, or actions, such as “You’re doing a good job“), person praise (implying that children have fixed, positive qualities, such as “You’re so smart“), or all other types of praise.

The researchers followed up with the children five years later when they were 7- to 8-year-olds, and gauged whether the children preferred challenging versus easy tasks, could figure out how to overcome setbacks, and believed that intelligence and personality traits can be developed (as opposed to being fixed).

When parents used more process praise while interacting with their children at home, children reported more positive approaches to challenges five years later, could think of more strategies to overcome setbacks, and believed that their traits could improve with effort. The other two types of praise (person praise and other praise) were not related to children’s responses, the study found, nor was the total amount of praise.

Moreover, although boys and girls received the same amount of praise overall, boys got significantly more process praise than girls. And five years later, boys were more likely to have positive attitudes about academic challenges than girls and to believe that intelligence could be improved, according to the study.

“These results are cause for concern because they suggest that parents may be inadvertently creating the mindset among girls that traits are fixed, leading to decreased motivation and persistence in the face of challenges and setbacks,” according to Gunderson.

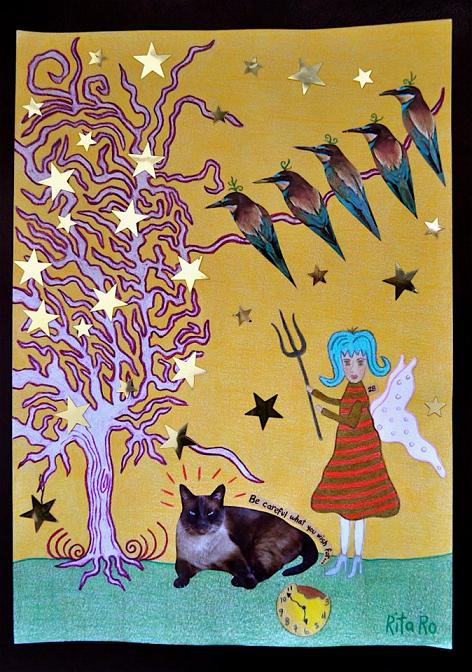

Illustration by Rita Ro

(Source: Society for Research in Child Development. Eurekalert)

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle