The somewhat fantastical world of Erased Tapes record making continues with Peter Broderick's Music for Confluence.

After the happy accident in which Nils Frahm's efforts not to wake the neighbours inspired the muted piano sound which defines his album Felt, comes Broderick's ambitious score to Vernon Lott and Jennifer Anderson's documentary film Confluence.

If there is a game being played in the Erased Tapes office, in which the competitors vie to come up with the best press release narrative, Frahm was going to be hard to beat. Some might argue that A Winged Victory for the Sullen's eponymous debut is unbeatable, having been recorded in Berlin's Grunewald Church and finished off in the old DDR East Berlin radio studios. For grandiose inspiration and historical gravitas, it would certainly be a frontrunner.

a game being played in the Erased Tapes office, in which the competitors vie to come up with the best press release narrative

Broderick though, takes another tack, opting for the musician's version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Somehow, within weeks of arriving in Berlin, he managed to find himself a living space above a music store, with the owner's permission to use the instruments whenever the shop was closed. Over the course of a snowy Berlin winter the twenty-four year old American set about creating a brooding, suggestive soundtrack which hints at depths of malevolence on occasion, but which never actually bullies the listener with exaggerated demands for emotion.

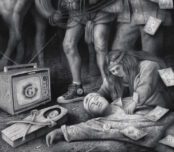

Presumably, the film supplies the rhetoric that Broderick refrains from stating openly. Confluence takes as its subject the disappearance or murder of a series of young girls from the area around Lewiston, Idaho. There is enough of a sense of despair in titles such as 'We Didn't Find Anything' and 'She Just Quit Coming to School' to convey adequate emotional unease without the record having to resort to the Jaws-cello cliches of musical tension-building.

Peter Broderick – Music For Confluence (album teaser) by erasedtapes

Confluence (Official Trailer) from Erased Tapes on Vimeo.

What remains is an album of music which at once presents the huge open spaces of the American midwest whilst preserving the random and total danger of the place. Folk violin strains flit in and out of the pieces, evoking the hard-won community of people living in harsh landscapes. There is comfort in those moments of folksy melody, but they are overpowered by the uneasy layers of cold soundscape and individual moments of twisted terror. In Music For Confluence, Broderick's Idaho has much in common with novelist Annie Proulx's Wyoming – it is the wide inhuman space which turns minds inwards and upon themselves.

uneasy layers of cold soundscape and individual moments of twisted terror

Predominantly string arrangements, echoing drones and piano, the album uses no small number of electronics in its build of texture and tension. Particularly effective are the looped samples of high-pitched vocal chattering on 'We Didn't Find Anything' and 'The Person of Interest'. The latter manages to integrate screeching electric guitar antics and electronic pitchbending into a piece which is otherwise carried by the elements of a traditional string quartet. The brooding malevolence of a heartbeat-like percussion pulse throughout the track is spellbinding, even if the spell is not a particularly comfortable one.

If not quite cornering the market in the new-classical mileu, Erased Tapes is certainly becoming a leading player in a sector of music-making which appears entirely immune to the devastating effects that have been wreaked on the rest of the music business in recent years. This is just not the type of music that people want to torrent from some faceless p2p site. Artistically, it demands an emotional investment from the listener.

Neither is it music which lends itself to the 21st century casual listening paradigm. You won't hear it blaring out of a phone on the back seat of a bus. It is this aspect of the new-classical, or near-classical (if we can call it that. Neo-classical is also being thrown around in reviews, but the term already belongs to the Victorian period and, as such, isn't really very useful) genre that is bolstering its resilience to the freetarding of recorded music. Near-classical sidesteps the devaluation of recorded music by appealing predominantly to those who appreciate music's deeper value.

a sector of that public has chosen to embrace art which draws upon a deeper set of ambitions

It can't be too far-fetched to imagine that in the flurry of throwaway product that the digital age has made available to the public, that a sector of that public has chosen to embrace art which draws upon a deeper set of ambitions. This is an album to be listened to, as an act in itself. It examines themes, expresses emotions, develops drama and tension and release. It disconcerts, soothes and, in the final vocal track, exerts a jaded wisdom on the listener.

All this whilst acknowledging the locality of its subject matter. It is, sonically, steeped in the American mid-west. A modern mid-west, with all the identity crisis that informs the character of the region. That fear for the loss of a way of life that, at the root of things, isn't even thoroughly sure of its own value in the first place.

A way of life which holds as its central virtues hardship endured over decades; the resilience of its few survivors of the 'dirty thirties' and the dustbowl. A culture founded in the isolated homesteads of the Roosevelt era; decimated by the westward drift of labour and population in the Hoover years; and typified by the hardening introspection of its remaining ranches and smalltown communities. Add to that the whole series of (perceived or real) betrayals of the region by successive administrations, making policy with no real idea of the realities of the vast but politically near-mute region, and you get some sense of context to the sonic tableau Broderick creates in Music for Confluence.

as much because of the isolation and difficulty as despite it, mid-west communities endured and endure

Even with all that, and as much because of the isolation and difficulty as despite it, mid-west communities endured and endure. Community and culture; establishment and misfits. Music for Confluence manages in its length, to somehow give voice to all of that – the strength of community; the maelstrom of hostile nature to be found outside of it; the determined and specific malevolence of individuals.

Previous to any of the white man's incursion into the area, Native American cultures of the mid-west and the Pacific northwest totemised various imaginings of the same trickster god – a random and cruel entity who in their shared mythology killed, maimed and stole unwary children. Our own culture shares the same myths, remembered now only through sanitised and diluted re-workings of the already re-worked Grimm's tales. The message is the same – community and conformity are where safety lies, outside of that – hell resides.

We can write it, explain it, put it into Powerpoint presentations. But as with all the most important messages, it is only through art that we ever feel such things at a deep enough level to learn from. Peter Broderick's Music for Confluence may have a different message for each person who hears it, but whatever that message is for each individual, the record has the ability to hammer it deeply into the parts of the psyche which are not easily accessed or acknowledged.

Peter Broderick – Music for Confluence

Out on Erased Tapes today

.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.