‘…composing and playing music is just a pretty sophisticated way to do those things we do, but why? Because we were separated in the big bang – and [are] now endlessly trying to find our joining cord?’.

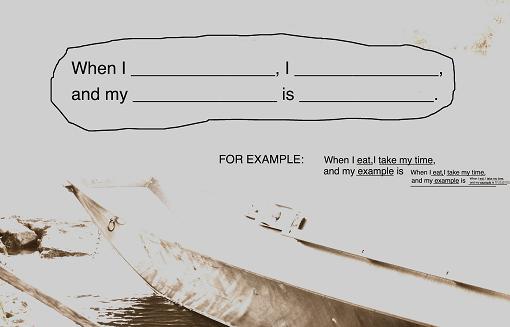

The theory is voiced on ‘I Do This’ as part of a dialogue between Peter Broderick and a clearly valued correspondent named ‘mitdenaugen’. Broderick crowd-sources his lyrics on the song, as well as on ‘When I Blank I Blank’, and mitdenaugen’s stunning response to the question ‘why do we do the things we do?’ outshines Broderick’s far more prosaic ‘I do this because I want to like me, and I want you to like me too’

In what seems initially to be an album of a singular, almost perversely personal nature, it turns out that the most insightful moments come as part of a dialogue.

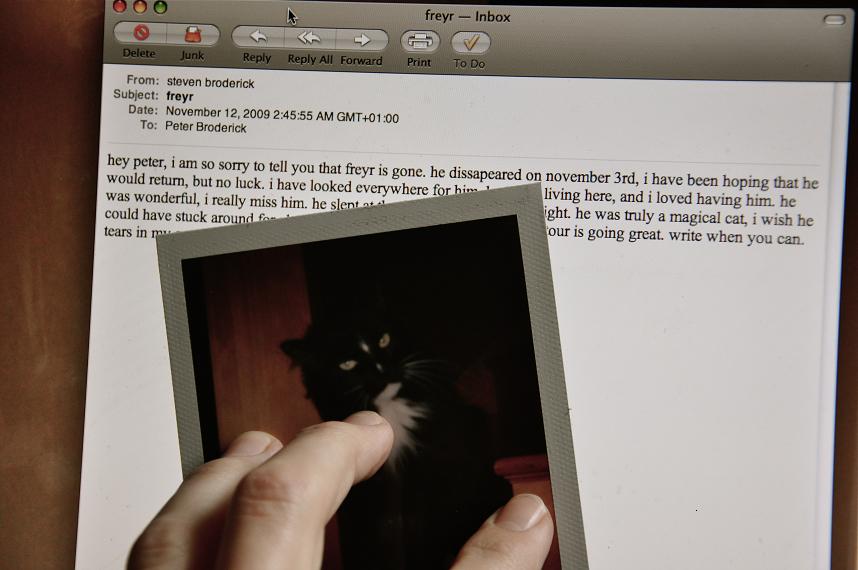

The epistolary mode of ‘I Do This’ is also caught in ‘Freyr!’, where the lyrical cadences of an email from Broderick’s father (concerning the death/disappearance of a much-loved cat) turn out, by juxtaposition, to be more honest and heartfelt than any of Broderick’s subsequent half-sung reminiscences of the cat in question (which include the memory of being peed upon by said feline).

Ostensibly about a cat, the dialogue speaks more of parental love, that awkward bond between fathers and sons which is deep though not demonstrative. In its lyrical tone and musical style, it reminds of Sonic Youth‘s paean to Karen Carpenter – ‘Tunic’

‘hey mom! look I’m up here – I finally made it

I’m playing the drums again too

don’t be sad – the band doesn’t sound half bad’

That intimacy of correspondence gets its echo in Broderick senior’s: ‘hope you are well and that the tour is going great. write when you can. tears in my eyes.’

On ‘Copenhagen Ducks’ a good-natured but heckling, voice punctuates the over-precious vocal narrative, which is rhapsodising naively over the poetic beauty of some ducks in a park, musically bolstered by some found-sound loops of a marching band. The secondary voice butts in, comments unnecessarily, puts the primary vocal off its stride somewhat.

It’s an effect famously used by Eels on ‘Novocaine for the Soul’, but works perfectly with the established theme of dialogue on the album as a whole. On ‘When I Blank I Blank’, Broderick’s correspondents once again provide the lyrics. In this case, Broderick asked people to fill in the blanks of the song’s title with their own ideas.

Elsewhere the dialogue is less overt, sidelined into a heckling role on one of the numerous vocal tracks that are chosen for the final mix. The presence of a multi-tracked vocal (Broderick harmonising and reinforcing his main line with different interpretations of the same vocals) is a near-constant on the album. Standard practice, although occasionally one of the vocals has a questioning, skeptical mien to it. In tone at least, it asks the same question of Broderick as anyone else who listens to the album surely will: is this for real?

Or perhaps, is it even possible to record something entirely personal any more, when dialogue and constant communication enforce collaboration and justification at every stage of the creative process? Broderick already includes audience reaction into the text of his work, a meta-narrative that is at once self-aware, and vaguely disquieting.

We know he can play it straight. Performing with Efterklang, or as a session musician with M. Ward, Broderick is no dilletante. His soundtrack album last year, Music for Confluence, showed a precocious talent for orchestration and lyricism far beyond the average. In the wide dramatic representation of open space, destructive environments, smalltown community fragility in the face of internal and external ravages, he has very few equals. Bringing that focus down, tighter, into the microcosm of existence that is himself and his correspondents, seems to challenge him more keenly.

Every album must convince on its own merits, and this is no exception, but it is worth noting Broderick’s previous fine musical form when deciding on how to approach this record. His musicianship, heard in the crisp and intricate violin swells on ‘I’ve Tried’, is beyond criticism. The violin lines are crisp, distinct, and discrete written parts in their own right. Not just flabby stringwash. The gospel harmonies on ‘Proposed Solution to the Mystery Of The Soul’ are competent, even if the lyrics offer nothing of the profundity of mitdenaugen’s loaned lines.

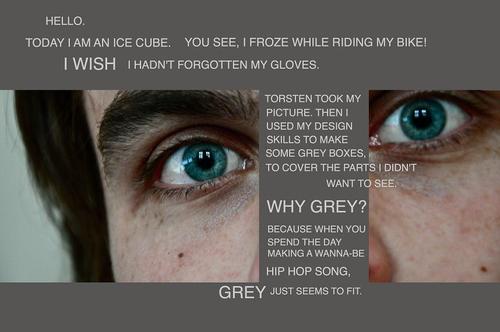

When he chooses to rap, Broderick over-extends himself

But the idiot-savant/unwitting genius moments of accidental profundity do not always come. When he chooses to rap, Broderick over-extends himself, and shatters the album’s intricately-wrought illusion. ‘These Walls of Mine Part One’ is introduced prosaically, straight-to-camera, recited deadpan in a cadence which brings the Dr Seuss books to mind. In part one we are told the time of recording and the nature of the project before the lyrics are read straight out.

When they are put to music in part two, the cringe of self-consciousness that has been ghosting the album all along becomes manifest. Peter Broderick raps with all the confident swagger of Sandi Toksvig on Whose Line is it Anyway? It’s a low point, and even when the lyrics explain the experiment:

‘Flowin’ may be weird but it’s better than just singin’ again

And even though I like to sing

I just think it’s fun to try everything’.

The song stretches the credibility too far, bursts the bubble.

That bubble is important, because on listening to These Walls of Mine, the album, the question ‘is this the work of an eccentric, egotistic, brilliant genius or just the random slobberings of an overindulged weirdo?’ is ever-present. Or as Robert Raths, label boss at Erased Tapes, puts it: ‘I haven’t decided if “These Walls of Mine” is genius or just freaky’.

‘These walls of Mine’ (song) is the make-or-break moment in relation to that question, and stretches credibility a little past the point of comfort. This, in an album where listener comfort/credibility is already tested at a number of junctures.

Erased Tapes run a tight ship in terms of quality control

The issue is to do with concept and intention. Cutting Broderick a break, and allowing the self-indulgence of an ill-judged attempt at hip-hop, and perhaps glossing over the slightly too-wacky second verse of ‘Freyr!’, the rest of the album is undoubtedly steeped in the genius that Raths suspects. Raths is mentioned here for the same reason as Efterklang, M.Ward and Music for Confluence – to establish credibility. Erased Tapes run a tight ship in terms of quality control, and that this album comes with the label’s endorsement is significant. There is no doubt whatsoever that repeated listening to These Walls of Mine reveals depths of composition, of character, tone and confidence that are unsettling. It is consistently interesting, rewarding, and in the simple guitar/vocal arrangement of ‘I Do This’, emotionally overwhelming.

An experimental album in the truest sense (the artist and label seem as unsure of its merits as the audience), it is a very fine thing indeed.

Recommended.

Out on October 22nd. Erased Tapes

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.