[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]hen Louise-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre demonstrated Daguerreotype in 1839 painting was forever changed.

As Dominique de Font-Réaulx reveals in his book Painting and Photography: 1839-1914 (2012) there is more to say “on the manner in which photography gave rise to a paradigm of representation at once original yet familiar….” than “through its choice of subject matter, its representational idiom, but also through the multiplication of the image brought by its dissemination, photography gave rise to a new relationship to reality and its representation, which then boomeranged on its elder sister”(Duggan 2013).

Clearly, representation is never the absolute mark of greatness for either photography or painting, and whether capturing or creating a scene, there is always the hand of the artist holding the brush or framing the shot. However, until the prominence of photography even the uncouth could understand, perhaps even need, a painting if the premise was accurate depiction. Which isn’t to claim that untutored appreciation of art fell silent with non-representation art. On the contrary, broad discussion about art blossomed as art’s central nexus moved inexorably toward subjectivism and abstraction. Statements like ‘my six- (or even three-) year-old could paint that’, ‘you’re so ugly you could be a modern art masterpiece’ and Rolf Harris’ statement ‘Can you see what it is yet?’ a hundred years later echo (perhaps parody) conservative critics regard for art that must be decoded.

Star Wars Girl Open Mag – Justin Hession

The parodied assumption that art is somehow hidden and elite, that the technical representational aspect of a work is the first threshold breached towards greatness, and even that aesthetics must always support the national frame. Where normative conceptions of beauty are often tinged towards racial, and thus national lines, representation is almost never about reality but about the audience, the artist, and an understanding. The nature of this became opaque before the formal object per se, as we started not to know what artists meant, then paintings became abstract. Photography freed us to move beyond the representation and to think symbolically at a level available to all. The appetite for meaning birthed abstract art, not the abstract vision. Van Gogh presaged much, but sold little. Almost pornographically, the constraints and canon of the salon where laid bare, open for abuse and without mystery, suddenly able to be ignored. Similarly, photography progressed quickly and, following painting, sought to become more nuanced. The idea that photography is flat and factual gave way to auteurs who used the medium to reveal, accentuate, hide and deceive – a tradition that continues to this day.

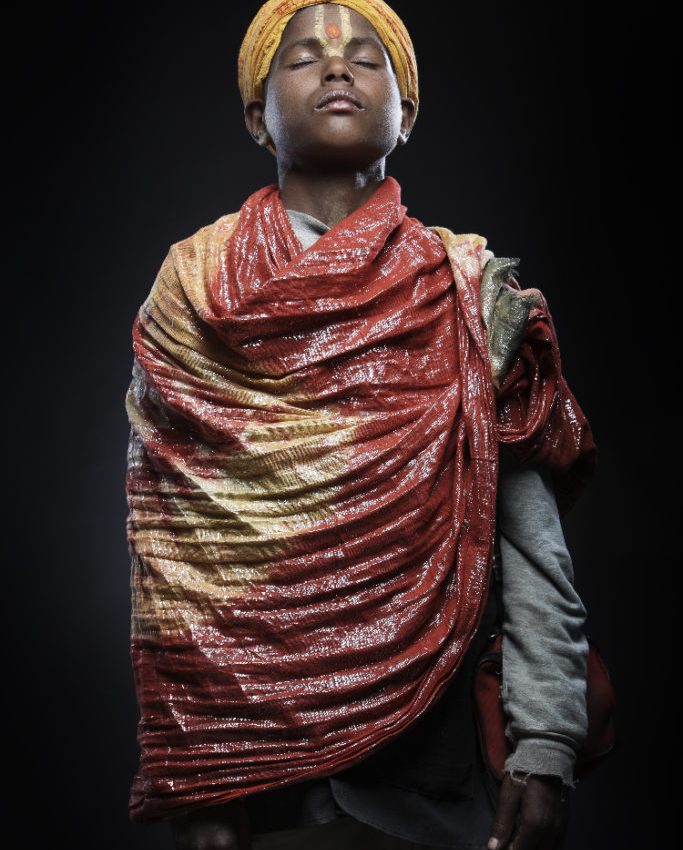

2013 Kumbh Mela, Allahabad, India – Justin Hession

Justin Hession started out as a photographer for News Corp in Melbourne Australia, but is now based in Switzerland. His work contains the characteristic shine of ’80s insert reportage with a wry joyous twist.

“I see portrait photography and portraiture (painting) very differently. They are different crafts that require different skills. There is occasionally crossover: skills like understanding lighting or posing, but how we work with these skills is very distinct. I studied photography in Australia and had a marvelous portrait teacher. We use to study the greats like Caravaggio and Sargent, but modern-day portrait photography has changed a lot over the years with the introduction of digital photography. Rarely do we ever get the time afforded to painters. Most of my work is done in under an hour, in fact probably more like 30 minutes, meaning that I have to learn to be calm and have the ability to connect quickly with the subject. A lot of the time I have a story that needs to be told with the portrait, so I need to quickly understand the subject’s character and what he or she is up for trying. The technical and creative aspects need to become second nature when working so fast like this. The challenge is very rewarding when it all falls into place…[Read more]

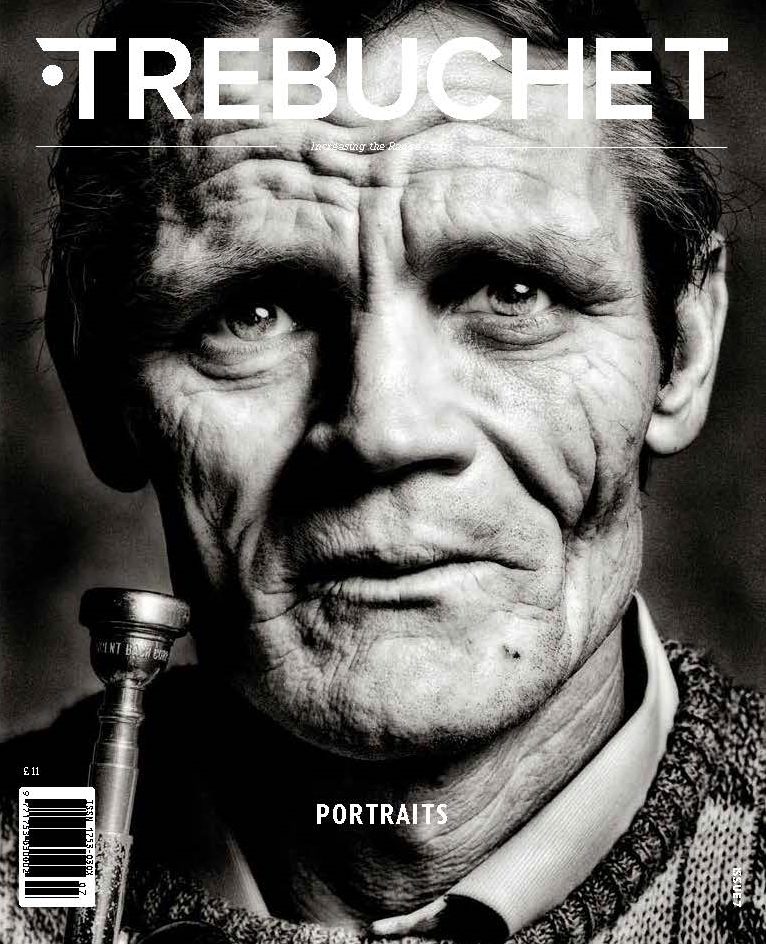

Read the full article in Trebuchet 7: Portraits

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle