When you’re trying to make a portrait of somebody you know well, you have to forget and forget until what you see astonishes you. Indeed, at the heart of any portrait which is alive, there is registered an absolute surprise surrounded by close intimacy. I’ll certainly be misunderstood but I’ll take a risk and say: to make a portrait is like fucking. (Berger, 2013: 160)

Such is the collaboration, the delicacy, the desire to see the essence of, to get to the heart of the subject in the portrait in John Berger’s delightful articulation of the art of portraiture.

Hail the new Etruscan

In 2018 Oona Grimes spent eight months on a Bridget Riley Fellowship at the British School of Rome, revisiting the films of the neorealists, which she had watched as a child and misremembered ever since. She made a significant shift in her practice to explore and to incorporate film making and performance for the first time, working these new practices into her material image-making.

Hail the new Etruscan has been instantiated thrice; the first was a show of drawings with stencilled colour and patchwork on black ground, at Danielle Arnaud. In the gallery notes, Grimes describes these drawings as comprising a storyboard: a filmmaker’s sketchbook concerning timeline, section breaks, thematic continuities (and discontinuities) and any other ideas that might attend the planning of a complex piece of film or video work that moves through temporal episodes to narrative effect. In her introduction, she writes,

Daily I would walk to Piazza Rotunda and beyond, just to be in Rome, early before the crowds; to watch the road sweepers and shop keepers setting up, to see the light changing over the city. Gradually those walks, and those [Italian neorealist] films wove themselves into my dreams and my drawings. (Grimes, 2019a)

The Piazza Rotunda—as dawn re-ignites the colour of the city, still sleepy for those awakening to work; those snorkling their first ‘spresso or kicking off with a grappa; ‘just a thimbleful to cut the phlegm’, as Dashiell Hammett had it; and gasping at their first mezzo toscano, or roll-up, already damp and gritty, scratching at the lungs; and for those, also emerging, made weary by traipsing the city; and whose rounds of the ancient streets have taken them through the night; their pallid faces reflecting the colours of the discreet, low-watt glimmer of night signage; now quenching parched throats with sobering bottles of birra Moretti—is the hub of Rome, the eternal city.

Imagine the early morning cafés in or around the Rotunda, the bright flourescent lights and the clatter of crockery on the marble- or zinc-topped bars, a jangle both repellent and convivial for the early bird and the nighthawk alike.

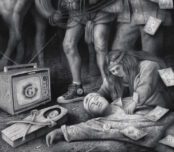

Grimes’ ragazze e ragazzi romani series brings us back into the night with images of the neon-lit sex clubs (is the Waikiki still operating?) and watering holes of the Roman demi-monde. Angelo del fango illuminates a dripping, spent penis adjacent to a young dancing girl who looks heavenward whilst thinking God knows what—or is it a tartan rag being wrung out, the drip from its tip, merely dirty water—or is the tartan graffiti penis stolen from some urchin’s scribble on a Roman wall, perhaps an illustration for one of Giuseppe Belli’s pungent, sonetti romaneschi?

The second instantiation was at Matt’s Gallery, where several short black-and-white films were shown in small, i-book format. In these films Grimes works to locate the gestures she has isolated and identified in the work of the Italian neorealists.

What impresses and puzzles is the gesture in the film and our understanding of the film as a work of art—interdepending, in no small part, on our understanding of photography; perhaps we always understood the photograph to be a still—abstracted from the continuum of the visual world. The gesture and the image are linked and our apprehension of the one in the other, I shall argue, is vital to our understanding of the nature of portraiture in photography and film. In isolating the gesture, as in mozzarella in carrozza, Grimes takes and visually quotes Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves.…[Read more]

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle