[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]J[/dropcap]ohn Berger sees portraits as enactments of social relations or moral values.

They also operate as an exchange of subjectivities, a mutual sizing-up. In the dialogue between sitter and viewer, the painter inhabits the nebulous space in between. As viewers, we are always aware of our own existence as experiencing beings. A good portrait is an active dialogue across a spatio-temporal zone. If the portrait we look at doesn’t capture something of its sitter which convinces us of similar activity in their ‘mind’, it won’t be successful.

And, according to John Berger at least, a successful portrait also constitutes a kind of social contract. Perhaps it’s a perpetually active discussion over the terms of a social contract. The status and expression of the painted person—their accoutrements, the colour-scheme they occupy, the curl of their lip and the glint in their eye, their posture, pose, and position in space—command a certain status, or reveal a certain vulnerability. They or beguile, or seduce, or do any of the other things of which human beings are capable when looking at one another.

In the marketplace, the terms of this contract become material. The purchasing of a portrait, anact of ownership, in some sense closes the dialogues described above. But it also includes many uncertain and arbitrary influencing factors like provenance, wily consignors, and auction-room competition. The value ascribed to a portrait has to do with a positioning of prestige outside of the picture’s own terms.

In December of 2009, Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man, Half-Length, With His Arms Akimbo (1659) sold for £20, 201,250 (about $33m) at Christie’s auction house in London. This represents the Dutch master’s highest price on the secondary market. But the factors which generated this figure are many, and impossible to quantify. The auction in which it sold—Old Masters and 19th Century Art Evening Sale—comfortably outstripped its estimate comfortably, raising a total of £111,450,215. This Rembrandt, and a Raphael portrait in graphite which sold for nearly $48m easily outperformed works by other masters which showed devotional subjects, stories from classical literature, or landscapes.

Perhaps one could extrapolate from this example that buyers have a taste for portraits, particularly those which provide intimate and revealing insights into the lives of human beings long dead, and particularly when observed by individuals with the skill of Rembrandt and Raphael. But, equally, the secondary art market may not be the zone for such conclusions. It’s often a place of safe subversion, riskless play. A place of monied gesturing, where prestige is all that matters.

The original impulse of portrait painting—a benefactor paying an artist to preserve their image for posterity—survives into the modern day. Chris Levine is an artist known for producing commissioned portraits of everyone from monarchs to Banksy. A version of Lightness of Being (2010), his now-famous portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, sold at Sotheby’s for around double its estimate earlier in the year, and a subsequent selection of his works at the London auction house in September generated similar interest…[Read more]

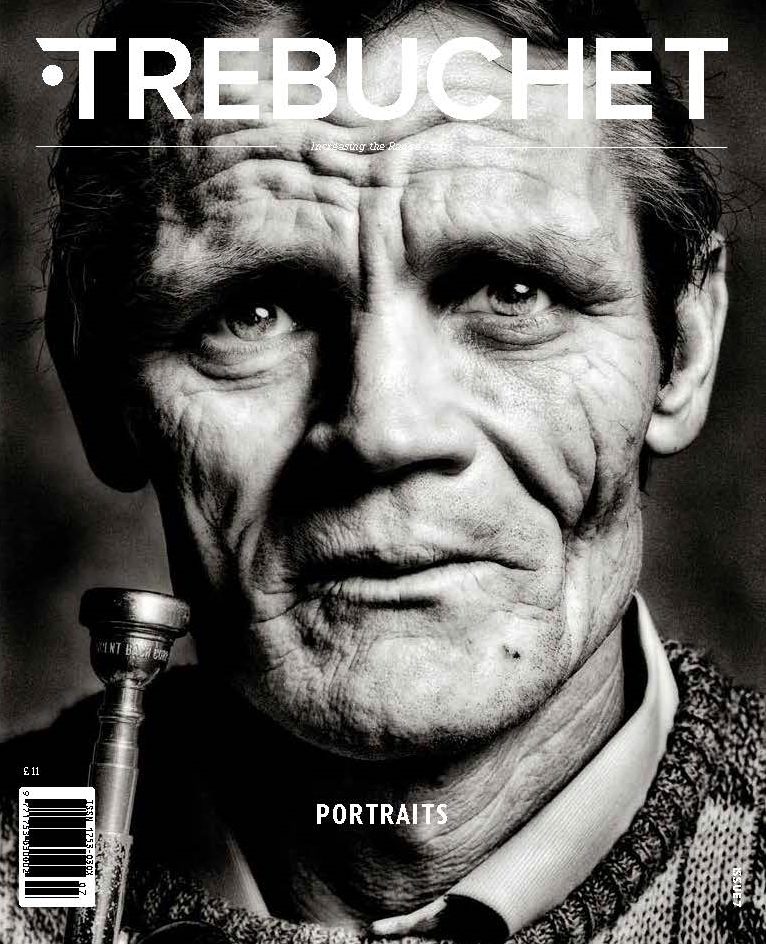

Read the full article in Trebuchet 7: Portraits

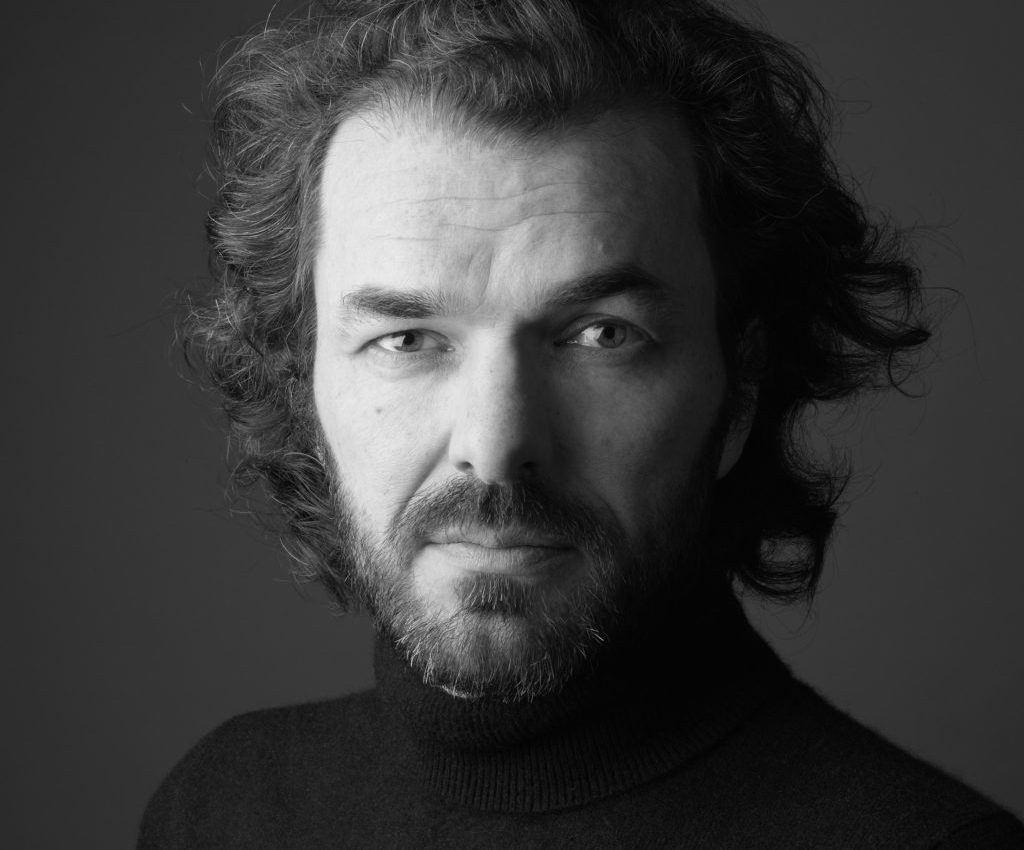

Portrait of Cyril-de-Commarque. Photo Jean-Baptiste-Huyn.

Adam Heardman is a writer, editor and researcher at MutualArt. Trebuchet’s Art intel partner MutualArt is an online art collector resource with information sourced from the World’s leading galleries, auctions and fairs. www.mutualart.com