[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he artist works from this invisible platform to make space-time visible, intimate and relevant on the shared plain. It will be useful in continuing this line of discourse to analyse Jorge Louis Borges’ short story, ‘“Funes the Memorious”.

In the story, the author reunites with an acquaintance from his boyhood, who in-between their last meeting has been bucked off a horse one day and knocked unconscious, to wake up ‘hopelessly crippled’ and yet equipped with a new, perfect memory which can recall in ‘exact’ detail every event of his own life and, indeed, every detail his senses consume:

“With one quick look, you and I perceive three wine glasses on a table; Funes perceived every grape that had been pressed into the wine and all the stalks and tendrils of its vineyard. He knew the forms of clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memory with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once”. […], “Nor were these memories simple—every visual image was linked to muscular sensations, thermal sensations and so on.”

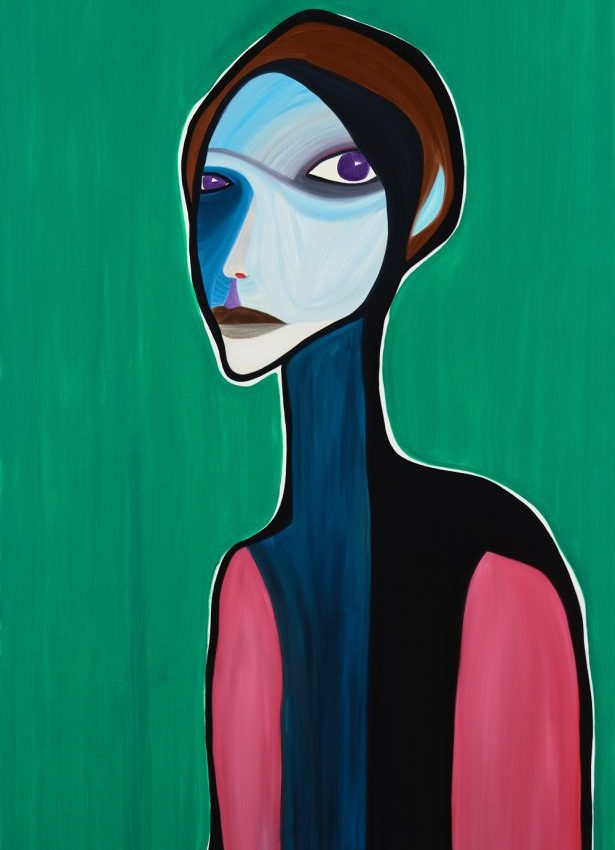

Self-Possession, 2018, Oil on Canvas, 150cm x 90cm © Trate

And yet, the problems with this superhuman, computer-like recording of memory data become quickly visible:

“Funes, we must not forget, was virtually incapable of general, Platonic ideas. Not only was it difficult for him to see that the generic symbol ‘dog’ took in all dissimilar individuals of all shapes and sizes, it irritated him that the ‘dog’ of three-fourteen in the afternoon, seen in profile, should be indicated by the same noun as the dog of three-fifteen, seen frontally […] He was the solitary, lucid spectator of a multiform, momentous, and almost unbearably precise world.”

As we are presented with a tragic character, obsessed with his own condition, Borges is opening us up to the idea that forgetting is a necessary function, like nothingness.

Pi is a decent example of this: it is the undefined door at the threshold of reality and possibility

Forgetting creates the void within which we can create our reality, furnish it with our imagination and subsequently connect with our kin to form intimate bonds of exchange and further learning, dreaming and refinement. Borges contemplates:

“He had effortlessly learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin; I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very good at thinking. To think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalise, to abstract.”

For Borges, thinking and dreaming is of more value than simply remembering. A human thought is always somewhat flawed because it seeks associations across the field of personal experience and shared history to form an imagined, congealed whole in the present. These cemented, imperfect thoughts become cornerstones from which point they can develop on towards new ideas that gradually improve and grow more refined. Pi is a decent example of this: it is the undefined door at the threshold of reality and possibility, and importantly, humanity has walked through that door. It may never be exact, nonetheless the utility of pi has made countless solutions possible. Similarly, memory is an imperfect tool from which we can expand or whittle down our reality. We may not remember our lives in full detail, however, we can generally extract enough so as not to repeat previous mistakes .

In assessing Funes through the Borges lens, it appears that we do not forget due to some incapability for our super computer brains to hold the data, rather, we forget because the creative play/connect/invent function of the human being has been more imperative than data recollection. Or more directly, perhaps the creative function has been made possible by the space created from forgetting, or simply ignoring. In this way, symbol creation is the essential punctuation and inheritance of a continuum of ideas. Funes does not write anything down ‘since anything he thought, even once, remained ineradicably with him’, whereas humankind developed generalised, imperfect systems to pass down our perceptions and allow common bases of connection to develop.

Interestingly, Funes is like a computer with senses. He is the epitome of a human desire to record, store and render the images of memory more perfectly, yet through him we see the folly of such a wish, how such a life could only lead to a maniacal recording of the past, eclipsing our faculty to think and create. Perhaps for this reason, long ago, we externalised computers instead of becoming them; thinking and creating being more essential to our survival, we began to dream and establish symbols that would one day be used to form the basis of computing in order that we may reclaim some shunned potential.

——

Precious Nothing Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 (Coming next week)

Read more on Art, Time and Space in Trebuchet 6

Nicholas Millen is an artist, gallerist and writer currently living and working in London.