[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap]rt is a by-product of a subjective mediation of reality, so maybe it is all self-portraiture. Most artists I know are narcissists, but some are better at hiding it than others! – Damien Meade

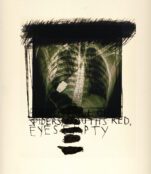

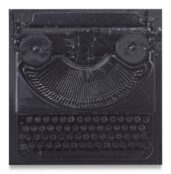

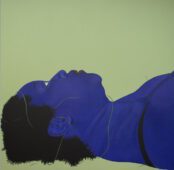

“Damien Meade’s paintings begin as mud, but live on as creatures of dirt. Minerals suspended in water are made compact—first by time, then the artist’s hand—and transform into something that Meade cannot, or at least does not want to name. Paint shifts onto linen panels like dried-up Play-Doh curling at its edges, creating what looks like hair, pairs of lips or the surface of skin, perhaps. In an unusual twist of tradition, this clay will never see the inside of a furnace. Instead, it stays wet and, once he is through, will be crushed and churned into the shape of Meade’s next model,” Olivia Fletcher for the Peter von Gallery

Meade (b. 1969, Ireland) lives and works in London. He obtained his MA in Fine Art from Chelsea College of Art. Meade creates paintings which are simultaneously melancholic and thought-provoking, exploring ideas of creation and destruction.

Meade references the modern digital world in his practice (manipulated images provide subject matter for works), combining this with a hands-on physical approach which sees him create sculptures that seem in process. This gives Meade’s work a strange status, virtual intruding into the material, a similarity to our time that is deliberate and uncanny.

Recently showing his work at the Peter von Kant Gallery in a solo show this serious, thoughtful and hands-on artist proves that painting is still a medium for deep thought and reflection.

How do you define the body?

The body, or the figure, is an oblique reference for me; a by-product of what I do. For me as an artist, thinking about my work strictly in terms of the convention of the body makes it very difficult to escape that convention. It is everything and it is nothing, which is a form of stagnation, so you have to develop disrespect for the convention, which results in a kind of iconoclasm. For me, the challenge is to trick yourself into ignoring it so that you might find it again. It is something counter-intuitive.

In what way do you feel you’ve pushed your conception and application of the body?

I’m not sure if I have, at least not consciously…

Read this article in full in Trebuchet 4 – The Body

Michael Eden is a visual artist, researcher and writer at the University of Arts London exploring relationships between monstrosity, subjectivity and landscape representation.