[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]”[/dropcap]Do you have a history of epilepsy?”

She held a bottle of smelling salts under my nose. I took another whiff. Whoa. My vision populated with blue and red and purple blotches.

She repeated herself: “Do you have a history of epilepsy?”

“No.” The world slowly drew into focus.

“You had a seizure.”

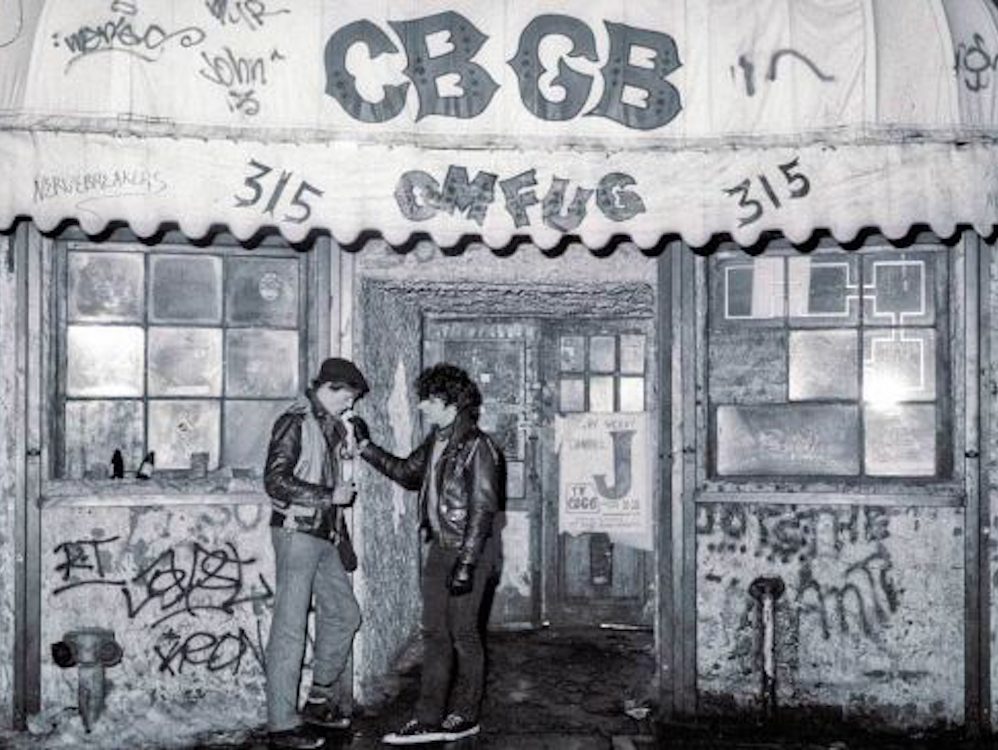

My head hurt. I was seated on a little chair at the front of CBGB, the infamous punk rock club, by the side of the entrance, near the office. I could hear a band playing. For years I used to joke that “the Outpatients knocked me out”, but that’s not what really happened.

She came back. “We need to call your parents so they can get you.”

“No… I’m fine.” I started to stand up.

“What’s your number? You passed out and now we can’t let you go. Your parents have to pick you up.”

She left. The door guy came over and said, “You’re not leaving. Give her your number.”

What was I going to do? There would be hell to pay. Worse than whatever had happened, I’d have to answer for it and make it somehow seem alright. My dad hated everything — and I mean every single thing — about hardcore: the music, the style, its underground character and radical refusal of social norms, and that it was mine to enjoy. One of the things he hated most was that it was based out of CBGB on the Bowery, New York City’s skid row of flop houses: a derelict zone of forgotten dreams and defeated souls set amid broken sidewalks decorated with shattered glass bottles of Thunderbird and Colt 45.

At the time, I was living with my grandma, and there was NO WAY that I could let them call her. Grandma was a worrywart and the idea that her grandson was damaged while out in the “forbidden zone” of the East Village would have realized her worst fears, and I’d never hear the end of it. Besides, the very idea of her coming into CBGB – which she mockingly referred to as “Heebie Jeebie” — was simply outside the realm of concrete possibility. Grandma and CBs didn’t exist on the same plane of existence, and bringing them together (though she only lived a few blocks away) would have been a water-and-oil mix of impossibility that would have collapsed reality as we know it.

So, they called my dad and he came in to the club. Our eyes met. I rose silently and followed him out and onto the Bowery. There was a cold reckoning: “Your mother and I work hard so that you and your brother don’t have to be in places like this, yet here you are.” The verdict having been already given, the inquest began. “Do you mind telling me what happened?”

“I passed out.”

I could sense both of his eyebrows going up. “Are you high?”

“No.” Which was the truth. I was stone-cold sober. Seriously, I was. “Do I have a history of epilepsy? I had a seizure.”

Dad had been around the block and he was not buying it: “Gimme a break. These people suck.” He never did mince words.

What could I say? How did I get into this stupid situation?

What Was Hardcore Punk?

In the early 1980s, if you were listening for a clarion call of rebellion, a semi-autonomous subculture of wild intellectuality, music as emotion, and the realness of a boot in the face, you came to hardcore. As The Ramones had offered a stripped-down version of rock, hardcore did the same for punk, making it even more primal, manic, and brief. And, as my first great musical love was Black Sabbath, the sound of hardcore resonated with me on a molecular level. Moreover, for a kid like me, who never fit into mainstream society, connecting to a scene that valorized outsider-ness was a hand-in-glove experience. It was the sound of the rejection of the rejects, as in: “You can’t fire me because I quit!” According to its own ideology, hardcore was not meant to be popular; it was not good-time music and it was definitely not going to get you laid. It was a totally uncompromising form of art, which is part of why it remains unpopular. The idea behind the genre was to create the most intense (fast, loud, emotionally-pitched) rock music and be completely unwavering in the process. Hardcore was about being hard in the core of one’s individuality: not seeking social approval. It was a Great Refusal of money and sex and popularity. Living that way was itself a provocation toward the outside world and, when we got together, we burned brightly. ‘Slam dancing’, ‘moshing’ and all that was a form of rough-housing, usually good-natured, but it also invited bad behavior. Hardcore was risky and dangerous, which, for a young person, made it all the more appealing.

Hardcore was made for kids like me by kids like me and it showed: shows and records were intentionally cheap, premiums were placed on passion and authenticity over technique, and the issues broached in the music defined my life. And it didn’t hurt that many of the bands were well read, which made the listening a challenge that stoked my intellectual curiosity. In addition to school, I learned history and ideas by studying fanzines and lyric sheets. Dead Kennedys satirically quoted Hitler, converting “Deutschland über alles” into “California über alles” with hilarious effect and powerful affect, and Crass tossed around quotes from Emerson and a million other authors. Taken altogether, there was an identity in all this that made me feel good about myself, and gave me the courage to do outrageous things that are part and parcel of the folly of youth.

The net effect of all this is that I followed literary leads from my records into my studies and came to excel at school for the first time in my life. Hardcore made it clear to me that trying to succeed in mainstream society — which, as a college kid, meant moronic drinking and the conformity of the frat house — was unworthy of time and spirit. When I wasn’t hanging with punk pals, I crammed ideas into my head. As a heady teen, notions of anarchy and socialism, then without voice in our media, sparkled with the exoticism and idealistic promise of an alternative universe. After all, I’d never seen what a politically-ascendant left-wing movement actually looked like, and the moral and analytical failings of their antecedents were seldom noted in the books I read. Furthermore, at its best, the East Village of Manhattan seemed a laboratory for actualizing anarchism. (When New York City Mayor Dinkins closed Tompkins Square Park for two years, he said it was because the neighborhood was “out of control”, and, indeed, it was.) While I was far from the coolest looking punk kid and I could never stay in a band, I could investigate leftist esoterica with the zeal of someone who thought such knowledge was actually useful and somehow cool. My overly pedantic sense of hardcore punk — all books and no brawl — would eventually run smack dab into a rough physical reality from which it never quite recovered.

New York Skinheads

Where there is a ying, there is also a yang. In the hardcore underworld, extreme ideas, left-wing and right-wing, came to exchange sharp elbows. There were no rules and no rulers, so anything went, including violence. Along with anarchistic ‘peace punks’, there were skinheads, many of whom had world views and lifestyles that were our mirror opposite: many chose religion (Hare Krishna), some were straight-edge (abstaining from drugs, alcohol, and sex), and all had a penchant for fighting. Despite some Nazi fetishism, they weren’t conspicuously racist or actively hateful of Jews. Aside from being somehow against the left, the skins didn’t have a coherent worldview, but seeing Roger Miret of Agnostic Front, a Cuban-American, playing in front of an American flag, summoned apoplexy among peace punks. I recall the patent absurdity of a big black female skinhead proudly declaiming, “I‘m more Aryan than anyone else here”, a ludicrous notion that was meant more as braggadocio than as a statement of fact. New York City skins loved to fight. In the early days, Harley Flanagan of the Cro-Mags and his crew cruised the Bowery with eight-balls in stockings to beat bums and homosexuals. They also liked to prey on scrawny, bookish, radical punks like me.

Coming into CBGB or walking by, one could sense danger in the air, which made it all seem important and exciting, like reliving the Weimar Republic in spikes and black leather. As I’d already encountered some violence in life, I accepted it as simply part of the equation. I was streetwise enough to never make eye contact with Harley or Roger or their closely-cropped toadies, let alone the Doc Marten Skinheads (DMS). More than once I even used ‘The Power of The Force’ to be invisible to skins in my vicinity.

During shows, I’d perch myself to the right of the stage, just outside the pit, or to the left of the stage, close-up, by the monitors, where I got a great view of the band and didn’t have to deal with the slam-dancing. Back then, skins were disinclined to committing open acts of unwarranted violence, preferring instead to create a pretense for fighting, and being in or near the pit made one the target of mischief: pile-ons, sucker punches, tripping, and group attacks. Even more than their love of violence — which was everywhere in their songs, album covers (Agnostic Front’s Victim in Pain LP sported a Nazi execution), T-shirts, etc. — skins loved winning a fight, and they didn’t care much for the chivalry of fair fighting.

For the punks I knew, skinheads were an unfortunate part of the scene, a constant nuisance that kept the milieu from attaining its potential. (I fondly recall, for example, how much fun The Effigies show at Rock Hotel was after Warzone played and the skins left.) Many punks dropped out of that scene by the middle 1980s. Some moved to other cities or left CBGB for the Lismar Lounge, Tin Pan Alley, or the Continental, and many moved on to other things in life altogether. I did a little of each, rarely re-engaging the hardcore NYC scene again until ABC No Rio started doing shows in 1990.

Back to the Scene of the Crime

When we got home, Dad told me that he’d beat me silly and banish me from his home as well as from grandma’s sweet little nest if I shaved my head. Mom warned me that she could not control him, which was unsettling. Surely, many of the punk kids I ran with had already gone through that sort of thing and were squatting. Thin, bespectacled, and asthmatic, I was not cut out for life on the streets and I knew it. So, while I’d have spiky hair, and a mustache that did not connect in the middle (my version of Fu Manchu’s famous whiskers), both taboo, I promised to never join the ranks of the baldies, which was something I didn’t really want to do, anyway.

The following week, I put on one of my punky T-shirts and went to the CBGB matinee, same as it ever was. During the intermission between bands, I stepped outside. There, Louis Ramos, a little Puerto Rican kid wearing a torn Sex Pistols T-shirt, engaged me on punk rock esoterica. We prattled on for a while, assessing each other’s level of cool and understanding of punk, and became fast friends.

A few months later, Louis confided that our meeting was not mere happenstance. He had sought me out because he saw the whole sordid affair, and he thought I was “hardcore” for coming back and acting as if nothing had happened. In other words, he thought I was crazy and all the more fascinating for it. A week earlier he saw me with my homemade Misfits T-shirt getting pulled toward the pit and getting “rabbit punched” in the back of the head by some skinhead. I went down immediately and hard. The crowd parted. For a few moments, I laid on the floor, twitching. No one knew what to do. The skin who hit me came forward, muttering “it was an accident” or some such. My body, as lifeless as a sack of potatoes, was half-carried and half-dragged to the front of CBGB. And the band played on.

Anarchy is a return to the natural order. Might makes right. If you are a punk in the pit, you might get hit. The zebra has stripes to confuse lions, but the camouflage only works when they run as a pack. The nail that stands up gets the beat down.

“Don’t go out alone

Go with a friend

You might need him

In the end”

– Minor Threat, “Stand Up”

New Yorker Jeffrey Wengrofsky has served on the staffs of Aperture magazine, Coilhouse, and Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory. Also a filmmaker and festival curator, Wengrofsky is now preparing to curate a night of films at the Babylon Kino in Berlin (date TBA). He now has open calls for films for Secrets of the Dead, to be held in NYC in October 2020, and Secret Treaties: Strange Political Bedfellows in 2021. Submit via FilmFreeway. His new film is A BLOOD ARTIST: www.humansyndicate.com/axel-2