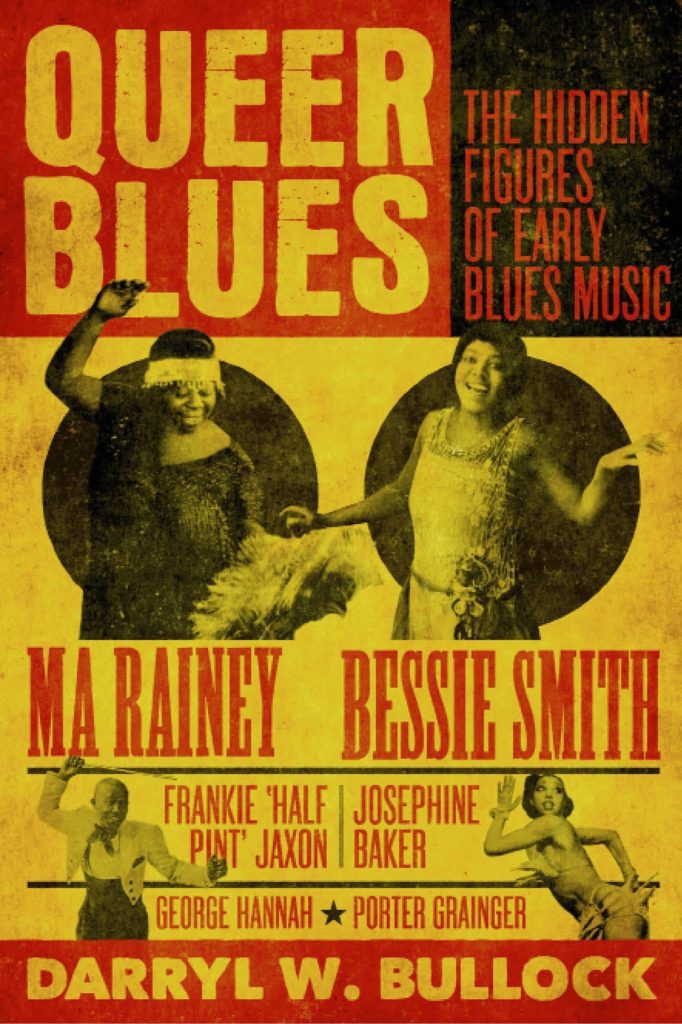

Listen to some blues records and what are they about? Oppression, destitution, love… sex? Old grainy recordings of many of these records can make the exact lyrics difficult to discern, but turn up the volume on your headphones and concentrate and so many of these lyrics are overtly sexual – so what about the sexuality of those making the music? If sex plays such a big role in lyrics, then surely sexual identity, or sexual fluidity, is crucial in understanding these artists and their creativity. If we want the full picture then recognition of historic LGBTQ lives has to be crucial – this is the argument of Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures of Early Blues Music.

Darryl W. Bullock has authored several books on music and LGBTQ history, including David Bowie Made Me Gay and The Velvet Mafia. Queer Blues, his latest outing, focuses on the sexuality and identity of musicians primarily operating in the 1920s and 30s, the heyday of ‘the blues’ (and jazz whose story is intertwined throughout the book). Using a wide range of primary sources including lyrics, letters and testimonies of those who were there, Bullock paints a picture of a period of sexual fluidity and a contrast between artists who found a way to live relatively open lives, and those who went to painstaking lengths to cover up their true identity.

At points, the premise that these are ‘hidden histories’ feels a bit strained. It is not revelatory that Josephine Baker had same sex relationships, for example. Nor is she a forgotten or hidden figure. However, there are enough generally obscure (to the blues laity) figures to balance this. The stories of Ma Rainey and Sammy Stewart – the leader of the wonderfully named Sammy Stewart and his Singing Syncopators – are particularly exciting to uncover. Bullock’s highly readable narrative style buys the reader in to the stories of these musicians and sparks an interest in their creative output.

‘Coming a time – women ain’t going to need to men

Coming a time – women ain’t going to need to men’

-Lucille Bogan ‘Women Won’t Need No Men’, 1927.

Central to the narrative is an understanding of the relative liberalism of the inter-war period in terms of not just sexuality but also culture. The 1920s stand out as a golden period prior to widespread censorship and the regressive conservatism that came with World War Two, and then the McCarthy era of the early cold war. An understanding that LGBTQ history is not linear in any true sense is needed for any serious understanding of identity. Bullock achieves this but also tempers this with that any openness was an openness relative to the time and still had to grapple with the attitudes and prejudices of the early twentieth century.

In this vein there is a strong intersection analysis present throughout the narrative. Bullock highlights that the lives of the figures in the book were also shaped by being (predominantly) black Americans in the era of Jim Crow. The long shadow and impact of slavery and the emergence from it, such as events as the Great Migration, shape the lives of the musicians in the book and the formation of the music they make. There is also a poignancy when talking about artists who went to Europe, Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson’s death in the bombing of Café De Paris in 1941, and Eve Adams the Jewish, lesbian activist and club owners death in Auschwitz are tragic points at the end of the book. As is Josephine’s Bakers absolute persecution and humiliation on her return to the U.S after her heroic war effort. Both her bisexuality and her race proved too much for the regressive conservatism of post-war America.

Historiography is emersed in such culture wars nonsense currently, such moral panic about the re-writing of history along ‘woke lines’ that books such as Queer Blues are important to demonstrate the important role LGBTQ people have played throughout history. Bullock avoids the pitfalls of assuming that just as two people shared a room they were lovers, whilst highlighting the real and impactful role sexuality played in these ‘hidden figures’ lives. Bullocks writing draws the reader in to the world of the blues and will hopefully inspire readers to find the music of these hidden figures.

Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures of Early Blues Music is published by Omnibus Press and Available Now.

Ruth O’Sullivan is a writer and curator. Her work explores the impact of digital technologies on contemporary art practices and challenging gender disparity within the visual arts.