[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t’s a typical Sunday in Harare. A cool wind breaks the heat, the streets are quiet, and everything is closed. The city center is dead.

For someone like me, who does not find his purpose through religious devotion, Sunday is a day of rest. It’s a day to sleep in, to have a barbeque, to read, to write, and to reflect on life.

For the majority of Zimbabweans, however, Sunday is a day of praise and worship, a day that lasts all day whether you like it or not. Whereas God rested on the seventh day, his followers work.

If you visit Zimbabwe, you may be curious to see women dressed in solid blocks of colour wandering the streets like nuns who’ve broken free from the convent. Men wear badges and carry Bibles. You’ll regularly find them underlining passages in their downtime as security guards, taxi drivers, and civil servants.

These are the worshipers, the men and women of the Apostolic Faith Mission Church and the Salvation Army.

These are the worshipers, the men and women of the Apostolic Faith Mission Church and the Salvation Army.

Religion in Africa is big business, as anyone who has lived here can tell you. At times, the faithful take it a bit too far. Pentecostal churches in Nigeria support organized witch hunts.

[quote]many here recognize that Mugabe

courted the religious vote in a

way that significantly boosted

his support[/quote]

Traditional healers in Tanzania slaughter albinos to concoct potions that will bring riches, for a price. Muslim marabouts in Senegal essentially control the country’s political system; it’s near impossible to get ahead without their blessing. South Africa’s Dutch Reformed Church collaborated extensively with the Afrikaaner nationalists to craft some of the most racist policies of that country’s apartheid regime.

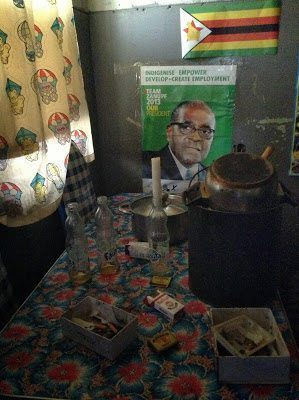

Zimbabwe especially, is a country marked by its faith. Here, pornography is illegal. President Mugabe regularly attacks gays and lesbians in his political speeches, an effective diatribe that garners him more than a modicum of support. Here, sex scandals have been used to discredit opposition party candidates.

MDC-T leader Morgan Tsvangarai has done more than his fair share to stir up tabloid rumors, though until his recent romantic trysts and troubles, the government-run media regularly questioned his sexuality in an  attempt to sully his reputation amongst average Zimbabweans.

attempt to sully his reputation amongst average Zimbabweans.

Like the United States, the politics of morality are an effective tool to capture a large bloc of eligible voters. Even with accusations of electoral fraud, many here recognize that Mugabe courted the religious vote in a way that significantly boosted his support throughout the country.

He attended weddings and funerals in the rural areas. He campaigned heavily to gain the support of the Apostolic church (one of the largest congregations in Zimbabwe with over 2.3 million faithful, making up nearly 20% of the population). While tabloids scrounged for stories about Tsvangarai’s sex life, Mugabe worshiped and prayed with some of the most ardent, and influential, members of the religious community.

This religious fervor can’t be underestimated. Driving through Harare and into the rural areas on a Sunday afternoon, one can scan the horizon and pick out a half dozen separate congregations kneeling in fields and on rocky outcrops. Clad all in white, they look like spirits floating through the dry, golden savanna.

[quote]Any time you find a church

that mentions fire, power, or suffering,

you can bet it’s run by a Nigerian[/quote]

These aren’t huge groups. They seem to number about thirty to fifty, growing until they reach a critical mass and break apart, a new group taking up another piece of land about fifty meters away.

The sermons last for hours, sometimes days.

“They sleep outside some days. They build fires, they cook meals, and they pray for days and days.” Barbara is a Zimbabwean who left the country seven years ago. She comes back a few times every year. “The head of the church is known as a prophet. He’s believed to see the future. He can communicate with God. You go and kneel in front of him like you’re talking to the Holy Spirit. They say, ‘okay, you have to do this, you have to do that.’ ”

“Then they pray over stones. You take the first water of the day, before anyone opens the tap, and you put the stone in the water. You have to drink the water three times a day, or bathe in it. It’s supposed to be healing.”

There are Catholics and Anglicans in Zimbabwe, but like much of Africa, the older denominations are slowly dying away, being replaced by syncretic models that combine traditional beliefs and spiritualism with Christian evangelical ideology.

Nigeria may be one of the biggest markets for this type of religious belief. Indeed, it’s practically an export. I’ve been continually surprised at the amount of major preachers from that country in this part of the continent. Any time you find a church that mentions fire, power, or suffering, you can bet it’s run by a Nigerian.

Religion is always a bit of a balm to ease the pain of everyday life. It’s no different here. Zimbabwe is a difficult place to live. Unemployment is high. Money is tight. People scrape by, if only barely. “In a way, from my point of view, it gives people hope,” says Barbara.

It might not feed the family, but for many, hope gets them through. It feeds the soul.

Photos:

Congregation: Apostolic Faith Mission Church, Zimbabwe

Mugabe poster: Sterling Carter

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.