[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]ince their 2015 appearance at The South Bank Centre, the Radiophonic Workshop has continued its renaissance, in marked contrast to the wider cultural shift away from Enlightenment values.

Perhaps they’re more in demand than ever precisely because they represent an agreeable but serious antidote to the regressive zeitgeist. Their appearance at The Science Museum was partly a promotion of the impressive new Mathematics Gallery and also a demonstration of the museum’s impressive IMAX screen. The circumstances of the evening were also tragically charged, coming as it did two days after the Grenfell Fire and with angry crowds outside the nearby Kensington Town Hall demanding answers.

An explicit (if not entirely natural) link to the mathematical theme was provided by musicologist and pianist Elaine Chew, who engagingly presented some of her research on music and mathematics and performed some computer-derived piano simulations of Bach’s style. These were interesting but I couldn’t help being reminded of the infamous piano playing of comedy great Les Dawson.

This was followed by a much-anticipated Q+A featuring the veteran Workshop members performing tonight (Roger Limb, Paddy Kingsland, Peter Howell and Mark Ayres). The discussion kept a good balance between studio talk and cheerful anecdotes and gave some new insights into the group’s past, present and future. One comic highlight was hearing about the logistical difficulties of wheeling the 1980s Fairlight CMI digital synthesizer around the confines of the Workshop’s BBC premises.

In the Workshop’s now-traditional style, further anecdotes and explanations were provided between many of the tracks, with relevant members introducing the pieces and giving insights into their creation and performance.

There were plenty of old favourites such as Peter Howell’s 1970s track ‘Space for Man’, accompanied by period footage of NASA space missions. The optimism and freshness they would originally have inspired now seem very distant, and the effect is of course warmly nostalgic rather than boldly futuristic.

There’s an unashamed nostalgic glee in the video to Howell’s 1978 B side ‘Magenta Court’ which shows the rotating BBC Records label spinning purposefully, reminding many in the audience of the vinyl they would have bought as children or teenagers and which in some cases they will have lost or stored away many years ago. Something about this rendition had slight Italo Disco traces that I’d not noticed previously, suggesting a wider connection between the Workshop and commercial popular culture that isn’t generally commented on.

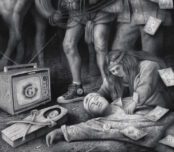

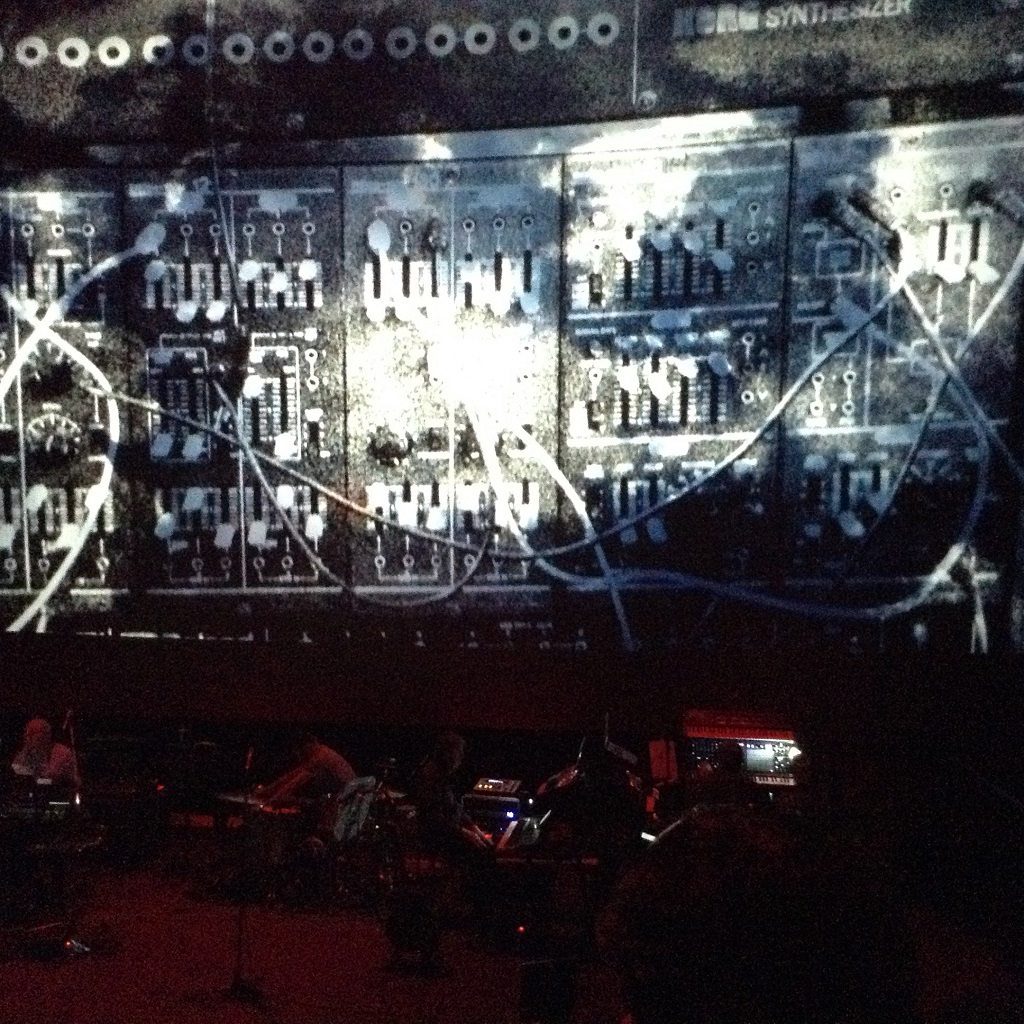

The Workshop know how to please the crowd and in a sense the mere fact of their presence is enough, but it’s also clear how much work they put in to deliver these live versions using banks of synthesisers and computers. Even if most are contemporary rather than vintage, after the show there was almost as much interest in the machines as the members.

Apart from the setting and the chance to use the IMAX screen and surround sound to good effect, what marked this show out was that it was a first chance for many to hear a live performance of the ambitious new album, Burials in Several Earths. It was explained that the album had been painstakingly edited and mixed from a single day of analogue experimentation, which meant that only a single extract was performed.

The surreal imagery of analogue equipment washed up on beaches is definitely striking and the performance retained much of the album’s distinctive balance between organic and analogue, reverie and unease. Above all though, it was tantalising. It would have been good to hear more in this vein and perhaps fewer of the funky, nostalgic crowd-pleasers. Unlike some other material the group have presented since getting together as a live act, Burials in Several Earths is serious and powerful and there must be others curious to hear more of this experimental mode in concert.

Perhaps rather than trying to recreate the album itself, a better approach would be to attempt a kind of ‘Radiophonic replugged’: a set of pu re electronics with no guitar, drums or other more conventional instrumentation. There must be many who’d love to witness these veterans in fully experimental mode, engaged in active sonic research and development, just as they did in the past. None of which is to say that this wasn’t a memorable night but it did leave me imagining something more than this quirkily English and idiosyncratic blend of styles and eras.

re electronics with no guitar, drums or other more conventional instrumentation. There must be many who’d love to witness these veterans in fully experimental mode, engaged in active sonic research and development, just as they did in the past. None of which is to say that this wasn’t a memorable night but it did leave me imagining something more than this quirkily English and idiosyncratic blend of styles and eras.

Another welcome surprise was a shortened version of a recent Picasso-inspired piece first performed at the National Gallery, a version of which has now been released on cassette as Everything You Can Imagine Is Real. The accompanying video ranged from close-up of Picasso details to a convincing use of the names of works and museums as a visual texture. The effect was quite hypnotic and the shifting nature of the sounds, conducted by Mark Ayres, worked well. Here again, it was a shame that more of this new material wasn’t played.

It’s symbolic that the show took place in the Science Museum – a state-of-the-art venue, but a museum nonetheless. Some of the material the Workshop produced decades ago is as more radical than much music produced now and the radical later modernism of the 1960s and 1970s seems to put to shame much contemporary culture. In this sense, its continued existence and development is implicitly critical of our era’s distrust of expertise and progress.

The Workshop operates on a temporal and cultural fault-line between then and now, progress and regress. So it’s inevitable that these tensions and contradictions also affect their work (here it’s worth remembering that their output was always much wider and more varied than is popularly remembered and it was also about entertainment as well as innovation and education). An evening with them is familiar and otherworldly, homely and un-homely, reassuring and disturbing and on this evidence there is still untapped potential and the possibility to resist the complete surrender to cosy nostalgia. These pioneers and their collaborators still seem to need to innovate and it may be that the cultural yearning and need for this is deeper than we realise.

From Speak and Spell to Laibach.