[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t worked out like this: I met Abdul in Harare. He was there on business, buying stock and meeting with wholesalers to supply his shop in Bulawayo.

The man, by his own admission, cannot function without his tea, something like ten or more cups a day, and that’s how we ran into one another, over his third cup of tea at one of the only backpackers in town.

We’d exchanged some pleasantries. With my hippy traveller beard, Abdul thought I was a fellow Muslim and offered to take me out to the Matopos if I ever made it back to Bulawayo. I was headed back that way anyway, and I was excited to see a part of the country that I couldn’t get to on my own. When I met up with Abdul, however, he had a different plan.

“My friend has been doing restoration work on the train car that brought Cecil John Rhodes’ body from Cape Town up to the Matopos for his burial. It’s one of a kind. You have to see it. Then tomorrow we can go out to the Matopos.”

Trains? That sounded about as exciting as a trip to the glue factory, but if it meant a free trip to the Matopos, then I couldn’t really turn it down. I can suffer through trains for an hour or two; it’s not like it’ll kill me.

When we rocked up to the museum, the guys running the place seemed genuinely surprised that they had visitors. A dollar bought us entrance, and it came with a free postcard commemorating some of the most famous trains in the museum. So… great, a post card. I’m going to continue to be a whiny child for this entire experience. Let’s just see some friggin’ trains, already.

“Oh, and by the way. We don’t have insurance, so if you want to climb on the trains, you do so at your own risk.”

Wait, what? We can climb on top of the trains?

F***ing rad!

Abdul, true to his word, had a friend who’d spent the past several months volunteering at the museum. A lot of restoration work had gone into the carriage that transported Cecil Rhodes’ body from Cape Town to the Matopos Hills for internment in 1902, stopping off at every city and small town along the way. It was Rhodes’ dying wish to be buried at World’s End, a rocky outcropping in the UNESCO-listed Matopos Hills, one of the most peaceful and beautiful places I’ve ever been.

[quote]You’re not cognizant of the power

of a single engine pulling ten or twelve

steel tubes full of people while rolling

along two thin rails. You don’t really think

about the wonders of engineering that it

took to lay track across hundreds of miles[/quote]

The funeral carriage is one of a kind, an American Pullman car built to carry one of Africa’s most famous and controversial colonial figures. Inside, it’s all leather and silver, dark wood and shining brass. It’s the type of place where you can almost smell the smoke from old cigars, where you can almost taste the imported Scotch. Where, if you listen closely, you can almost hear the brash trumpet roar of racist imperialism, of “Empire” and oppression.

As a historical artifact, the carriage is interesting in and of itself, but the real treat is outside, in the rail yards, where dozens of train cars, engines, and rail ties sit out slowly collecting dust and rusting away in the African sun.

I’d forgotten how awesome trains are. I don’t mean that in an awe-inspiring sense, nor do I mean it how most Americans use it, i.e. as a replacement for ‘cool.’ No, I’m giving voice to my seven-year old boy self when I say, “Trains are AWESOME.” Think about it. When did you last spend some time around old trains? I lived in London for a couple of years. I used trains quite frequently, but when it comes to your morning commute or your trip down to Brighton, the train becomes nothing more than a bus on rails.

You’re not cognizant of the power of a single engine pulling ten or twelve steel tubes full of people while rolling along two thin rails. You don’t really think about the wonders of engineering that it took to lay track across hundreds of miles – over fields, across rivers, even winding around mountains. It doesn’t really hit you, in the modern train, that for nearly a century, these behemoths belched coal and hissed steam like some metal dragon.

Modern trains glide on electric rails, the carriages are soundproofed, and arriving at a station is little different than stepping off a bus in the suburbs. Those older locomotives, however, were the pinnacle of Industrial Era engineering. They combined power and comfort. Disembarking onto a platform, where the porters took your bags and conductors whistled departures while glancing at gold pocket watches, this is part of the romance of that era, one that may never have existed but nonetheless exists in my mind.

The beasts that slept in the Bulawayo train yard were from a different era. All of them saw Rhodesia declare unilateral independence from Great Britain. All of them witnessed the handover from Ian Smith’s minority rule to Robert Mugabe’s majority dictatorship. Their faded paint harks back to the Rhodesian Railways, in the first half of the twentieth century, a different time. Some might argue, a different place.

One of the oldest, a smaller green and red engine that looked like it’d be right at home with Thomas, Oliver, and all the other trains on the Island of Sodor, logged over a million miles as it built the rail lines from the Cape all the way up to present-day Zambia, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. It even had a name, Jack Tar, that gave it the character and personality of a robust, Victorian adventurer.

Other than this old adventurer and the Rhodes’ carriage, everything else in the museum sat open and uncared for. It was as if the railway just dumped their old equipment here when it stopped working. The museum is essentially a junkyard, but like any good junkyard, the lack of barriers, guards, and restraints opens up opportunities for discovery and play unavailable in a typical museum. Engine compartments stood open, giving us access to switches, levers, wheels, and pulleys.

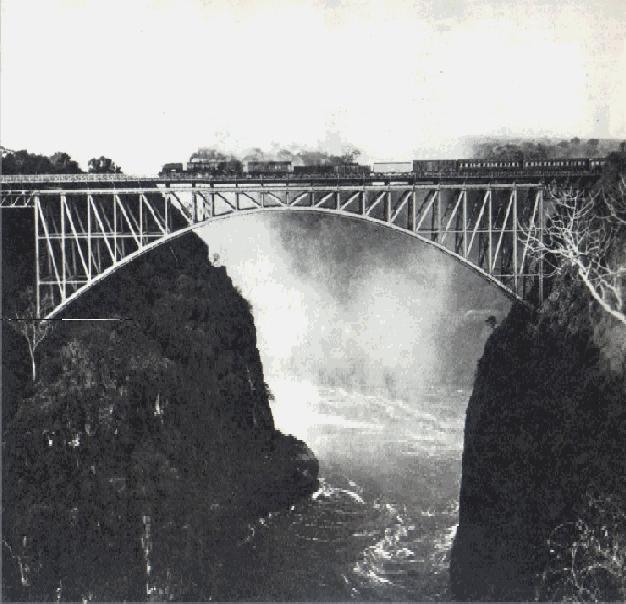

”Let the spray from the falling Zambesi River fall on the trains as they pass.’ – Cecil Rhodes

”Let the spray from the falling Zambesi River fall on the trains as they pass.’ – Cecil Rhodes

Suddenly, I was driving a train (figuratively) rushing passengers up on the night train to Lusaka, or hauling coal to the power plants in South Africa. Forcing a door led me into an engine room, where I was a greasy mechanic, covered in engine oil and coal dust, trying to jerry-rig a fix on the move so we could get the antibiotics to the cholera patients on time. I was a porter delivering coffee to some early risers on sleeper to Vic Falls. I was on the Orient Express; there was a mystery to solve. I climbed on top of some old passenger cars, and suddenly, I was Indiana Jones in The Last Crusade: “It belongs in a museum!” I was James Bond in Skyfall, running across the carriages to retrieve the list of NATO agents from the nameless assassin.

I don’t know what came over me, but there is something undeniably exhilarating about being able to tap into your inner child and lose yourself in play. By the end of the day, I was covered in a combination of grease, coal dust, and dirt. My hands were black. I wouldn’t be surprised if I had smudges on my face as well. As the sun set, I hopped on a handcar and ran it up and down the rails, only to spy a small kid watching, smiling, shy. It was obvious he wanted to play too, but he was too small to run the handcar, so I chucked him up and ran it back and forth until we nearly crashed it into another locomotive.

If you’d have told me a month ago that one of the best experience I would have in Zimbabwe would take place at a nearly defunct railway museum, I’d have looked at you like you have two heads. After all, this is a country with five UNESCO World Heritage sites. It’s home to some of the most beautiful scenery in Southern Africa as well as some of its nicest people.

It’s evidently also home to a dusty, broken down railway museum, one that, if you allow it, may help you unlock your inner child.

Bulawayo Railway Museum photo by H.G. Graser

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.