[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap] short title for many art exhibitions these days and yet one that promises, or is suggestive of, so much.

Notions of desire and aesthetic pleasure immediately come to mind, offering up an exploration into different types of desire in the themes and subjects of the work displayed. Perhaps less obviously, ‘Ruin Lust’ also directly references the book by Rose Macaulay called Pleasure of Ruins (1953), which looks at the nostalgic pleasures of monuments and ruins of civilisation across different periods and cultures.

Not having been to a Press View of an exhibition before, I was eager to see how the journalists would ‘make’ something out of ruins, how they physically go about constructing stories – and mapping histories – out the wreckage of a past presented in specific, and often political, contexts.

This idea of creation out of destruction is one of the prominent themes of the exhibition itself. An important part of this aesthetic and potentially political idea is the notion that ruins can point towards futures, potentials, opportunities and constructions of the new, as well as to endings, such as the end of Empire (a particular trope for which ruins were used in the 18th and 19th centuries), failures and even degeneration.

In this way, ‘Ruin Lust’ aims to include investigations of both obvious and more surprising ways in which ruins have been used from the 16th century onwards. It is both a serious and humorous project. This sense of duality is something the exhibition cultivates in terms of themes, artists and curatorial decisions of presentation.

An anxious mixture

Brian Dillon, co-curator of the show, stated that the curatorial team aimed to create “an anxious mixture of different time scales” by juxtaposing artwork from different periods.

John Martin, ‘The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum’

John Martin, ‘The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum’

This is startlingly achieved in the first room through the decision to partner John Martin‘s painting ‘The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum’ (1822) – a work focused on ruins of the sublime – with John Constables‘s painting ‘Sketch for ‘Hadleigh Castle’ (1828-9), exemplary of the picturesque.

So already we have arguably oppositional Romantic binaries at play. The first room also confronts us with the monumentally-scaled photograph ‘Azeville’ (2006) by Jane and Louise Wilson, which presents a modernist postwar ruin. It is this piece that powerfully brings in the exhibition’s concentration on Brutalist architecture. Through these bold, and yet careful, juxtapositions, Dillon’s desire to create “confusion and surprise” in the viewer is achieved in the opening room alone.

Why shouldn’t ruins be colourful?

John Martin’s painting also introduces a concern with aesthetics. What struck me was the intense colouration of the violent scene. Rich reds and violets are not colours I think one would immediately, or naturally, associate with ruins. I don’t think we tend to associate ruins with colour – does this reference black and white documentary photography and our associations of ruins with ancient histories? ‘Ruin Lust’ immediately challenges these assumptions: why shouldn’t ruins be colourful?

Martin’s painting is also important aesthetically because it is a ‘ruin’ in both its subject matter and its materials. It became a ‘ruin’ itself in 1928 when it was badly damaged in a flood at the Tate gallery. Arguably, materiality is a great concern when thinking of ruins. What do materials tell us about ruins and their construction? And what can they signify about the nature of their destruction? How can emphasis on concrete materiality make us perceive ruins in a fresh (and constructive) way?

Materiality is called to attention in the second room too: the material aspect stands out because of the dense hanging of the paintings. This automatically engages with the notion that ruins create material just as much as they can irreversibly destroy it.

However, Amy Concannon, a co-curator, explained that the dense hang was chosen to reflect the 18th and 19th centuries’ craze for ruins. Artists, writers and tourists were all searching for aesthetic pleasures from ruins in Britain and beyond. Indeed, the 19th century was the Age of the Grand Tour, which in turn gave rise to domestic tourism as people started to explore ruins closer to home.

Clear idealisation of the ruins of Tintern Abbey is seen in the watercolours by JMW Turner and Peter Van Lerberghe in this second room. These watercolours fulfill the demand by tourism in this period for both the picturesque and the sublime.

Furthermore, tourism is referenced through the intersection between art, documentation and commerce that is played out in Alfred and John Bool‘s photographic series on an adjacent wall. The photographs are suggestive of the multiple agendae and discourses that representations of ruins were attempting to access and ‘profit’ from. Overall, they do seem to claim ruins as relics.

Dillon asserted that Surrealism is a big factor in the role of the ruin, which this exhibition successfully – and humorously – emphasises. Paul Nash‘s photographs in the penultimate room best exemplify this through their focus on the details of ‘odd’ objects in ‘odd’ locations in the British landscape. This work is in dialogue with the artist’s essay ‘The Life of the Inanimate Object’ which talks about giving objects a mystical character and creating strangeness through the juxtaposition of the natural with the manmade.

The theme of the natural ruin is prominent in this photographic series too, with trees taking on monstrous identities. Here, the theme of the British landscape intersects with an exploration of ruins a way that positions the landscape as something that is both comforting and bizarre.

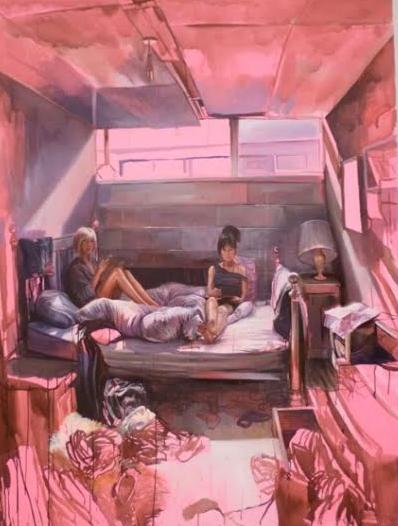

When ruin points towards the future in ‘Ruin Lust’ its subject matter is usually that of London. There are distinctive threads of fantasies about its own destruction. Some of the most striking contemporary work is by Laura Oldfield Ford, an artist who emerged out of cultures of punk and squatting. She mostly explores postwar housing estates, Brutalist architecture and their ruinations.

Laura Oldfield Ford, ‘Tweed House, Teviot Street’,

Laura Oldfield Ford, ‘Tweed House, Teviot Street’,

Dillon talked about these buildings as “sites of desire” for something that is about to happen; a kind of political emergency which is suggested by the fact that her largest painting, ‘Tweed House, Teviot Street’ (2012) was completed soon after the 2011 riots. Political references in her work act as inspiration for us to think about how we create, imagine and relate to the cities and enclosed spaces in which we live.

When do ruins stop and wreckages begin?

Unusually, Oldfield Ford depicts ruins from the inside. This allows for a focus upon the human, and on the relationship and interaction between people and ruinous, urban landscapes. It also literally turns the notion of ruins inside out. Focusing on familiar, recent (interior) urban landscapes does beg the question of whether recent wreckages can be called ‘ruins’. When do ruins stop and wreckages begin?

These questions can be interpreted as contributing to the exhibition’s intellectual debates, but it also makes me wonder if ‘Ruin Lust’ is trying to include too much. Perhaps my questioning of this stems from the inherent modern anxiety about the meeting between the new and the recently decayed that ‘Ruin Lust’ attempts to negotiate.

Where there are fascinations for postwar ruins, Tacita Dean is always involved. Dean’s work occupies its own room (and film room) with photographs selected from her The Russian Ending series from 2001. This series, like a lot of her work, explores meetings between obsolete technology and architecture, pointing towards ruination of mediums and their aesthetics.

Neither could there be an exhibition about ruins without including some of John Piper’s paintings. Piper’s work draws attention to the fact that postwar art representing ruins retain aesthetics from the Romantic period, even though much of his work aimed to record the broken urban landscape and was commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee to do so.

Ruins to remind us of the disillusions of war

Piper wrote an article published in Architectural Review, 1941, detailing the aesthetic opportunities and artistic potentials of buildings that had been subjected to weathering over the centuries or ruined by manmade destruction. He even wrote that some buildings could be left as ruins to remind us of the disillusions of war. In this way the artist was thinking through how the past impacts upon the present, influencing its politics and pleasures, and how histories could be represented in the future.

The title of one room, ‘Ruins in Reverse’, a phrase coined by Robert Smithson, extrapolates this idea through its concentration on thinking through how modernity sees itself to produce ruins. There is undoubtedly anxiety produced by this temporal confusion, as well as a more positive or energetic reading of ruins that help us to imagine not only the present but also the future.

Dillon was keen to point out that the persistence of ruins is a key theme of ‘Ruin Lust’; indeed the persistence of classical ruins in 20th century art is something is exhibition is careful to map. However, this persistence is certainly coupled with ambivalence and an anxiety about objects, but this doesn’t stop us noticing that ruins can be resilient and act as markers for the survival of societies.

Certainly, the histories of ruins continue.

Ruin Lust

Supported by Tate Patrons

4 March – 18 May 2014

Tate Britain, Level 2 Galleries

Installation photos by Helen Cobby

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby