[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]

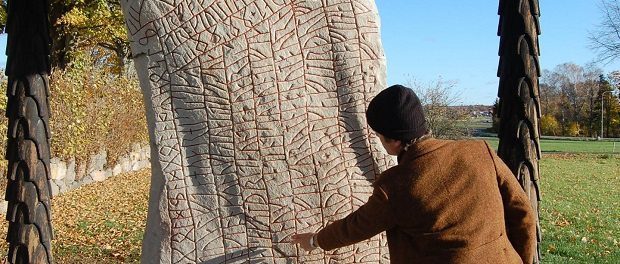

ntroducing a news piece about runic inscriptions on Swedish monoliths comes with a desperate temptation to make all sorts of laboured references to Nordic music culture.

It’s rock, ferchrissakes, in a country oozing with bands doing variations on Viking metal, Scandi-doomsludge, runic deathcore, and variations on the theme we haven’t even invented terms for yet.

And yet it turns out that the runes on the Rök Runestone may not actually be anything at all to do with battles, armies, plunder, pillage or any of those other thematic staples of Sweden’s tune-mongers, meaning that any reference to Swedish music would be wholly inappropriate and TO BE AVOIDED. In fact, it seems that the inscription is a paen to the art of rune-carving itself. An early appreciation of the simple act of written communication.

Almost like a stone-carved literary version of ‘Thank You for The Music’.

Gah.

The Rök Runestone, erected in the late 800s in the Swedish province of Östergötland, is the world’s best-known runestone. Its long inscription has seemed impossible to understand, despite the fact that it is relatively easy to read. A new interpretation of the inscription has now been presented – an interpretation that breaks completely with a century-old interpretative tradition. What has previously been understood as references to heroic feats, kings and wars in fact seems to refer to the monument itself.

‘The inscription on the Rök Runestone is not as hard to understand as previously thought,’ says Per Holmberg, associate professor of Scandinavian languages at the University of Gothenburg. ‘The riddles on the front of the stone have to do with the daylight that we need to be able to read the runes, and on the back are riddles that probably have to do with the carving of the runes and the runic alphabet, the so called futhark.’

Previous research has treated the Rök Runestone as a unique runestone that gives accounts of long forgotten acts of heroism. This understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions on the stone, was related to Gothic kings. In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök Runestone can be understood as more similar to other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, runestone inscriptions say something about themselves.

‘Already 10 years ago, the linguist Professor Bo Ralph proposed that the old idea that the Rök Runestone says mentions the Gothic emperor Theodoric is based on a minor reading error and a major portion of nationalistic wishful thinking. What has been missing is an interpretation of the whole inscription that is unaffected by such fantasies.’

Holmberg’s study is based on social semiotics, a theory about how language is a potential for realizing meaning in different types of texts and contexts.

‘Without a modern text theory, it would not have been possible to explore which meanings are the most important for runestones. Nor would it have been possible to test the hypothesis that the Rök Runestone expresses similar meanings as other runestones, despite the fact that its inscription is unusually long.’

One feature of the Rök Runestone that researchers have struggled with is that its inscription begins by listing in numerical order what it wants the reader to guess (‘Secondly, say who…’), but then seems to skip all the way to ‘twelfth, …’. Previous research has assumed there was an oral version of the message that included the missing nine riddles. Holmberg reaches a surprising conclusion:

‘If you let the inscription lead you step by step around the stone, the twelfth actually appears as the twelfth thing the reader is supposed to consider. It’s not the inscription that skips over something. It’s the researchers that have taken a wrong way through the inscription, in order to make it be about heroic deeds.’

For over a century, the traditional interpretation has contributed to our understanding of the Viking Age. With the new interpretation, the Rök Runestone does not carry a message of honour and vengeance. Instead the message concerns how the technology of writing gives us an opportunity to commemorate those who have passed away.

Source: Eurekalert/University of Gothenburg

Image: University of Gothenburg

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.