[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he world’s first major museum exhibition of Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair, a unique female voice from the Beirut art scene of the 1940s.

Visitors are led through a diverse display of works- from sculptures of the 1950s and 80s to early abstract paintings and textiles and jewellery- in a showcase of her interests in mathematics, poetry, Islamic art and science. Collectively they illustrate her influences from western abstraction and Islamic design and place her rightfully as a pioneer in the realms of abstract art.

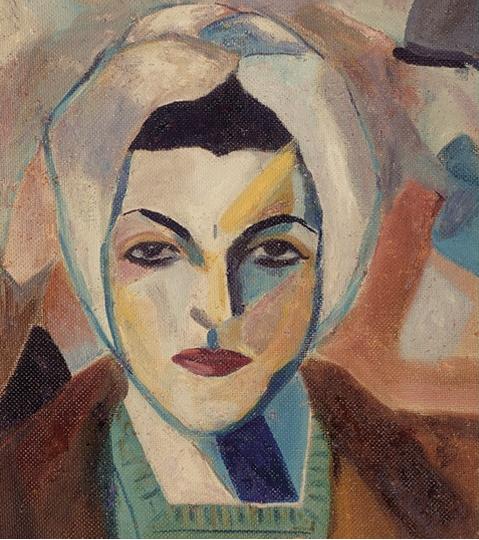

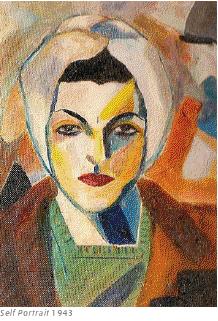

It is difficult to escape the stony eyes of Choucair’s self-portrait gazing unerringly out from the cover of the exhibition catalogue as you navigate the bustling thoroughfares of Tate Modern. If, however, your assumption is that this will be an exhibition haunted by the voice of a pervading artistic ego then you may leave in a state of confusion.

One thing that seems evident from the outset of the exhibition is that, in the case of the latter, Choucair is not portrayed as an artist ready to follow another’s dogma. The works elsewhere are thereby permitted their own voice; the focus of the viewer is trained on the form, not on the personality of an artist- somehow the spectre of Lichtenstein lurking a floor below is brought to mind.

The opening paintings from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts are a stamp of Choucair’s intent; “Les Peintres Celebrés” are a challenge, but the question becomes more and more pertinent as to whom is this challenge addressed? Unlike the ruffle-rumpling, accusatory gaze of Manet’s Olympia, Choucair’s women look out at the viewer with a directness which is enigmatic, somehow expectant or impatient; is Choucair’s intent a challenge, or is it following the ins and outs of a particular school of learning?

[quote]it is her

unique position as

an outsider that

has allowed the

structures to develop[/quote]

In light of this, her studies under Mustafa Farroukh, Omar Onsi, Fernand Léger, and repeated journeys to broaden her skill-base seem more like the strivings of an artist committed to finding her own path. Perhaps then, her intent was to claim a position for herself both as a female artist at a time dominated by men and as a particular kind of artist with a unique array of cultural and personal influences, with Les Peintres Celebrés as her flag.

The studies for rugs and textile pieces reveal the breadth of Choucair’s practice and foreground the intermingling of craft with art, a technique that becomes more evident in the unfinished quality of her sculptures. This concern lends itself to parallels with the feminist artists of the 1970’s and 80’s though; in Choucair’s case, this appears to be less of an ideological position than a natural and practical expression of cultural influences.

The palette Choucair draws from seems to recall images of Beirut: the sandy Mediterranean climate somehow rendered in the subdued pastel quality of her colours.  In addition, the flattening of the image and block colours of paint speak of a high-modern aesthetic, which teeters on the edge of abstraction in works such as “Paris-Beirut”, and leaps over the precipice in “Composition in Blue”.

In addition, the flattening of the image and block colours of paint speak of a high-modern aesthetic, which teeters on the edge of abstraction in works such as “Paris-Beirut”, and leaps over the precipice in “Composition in Blue”.

This apparent turning point in her work leads on to an overt rejection of figuration in the latter part of her career. The painterly language becomes more abstracted. There is an emphasis on repetition and geometry which draws on her interests in science and mathematics, and in the arithmetical basis of Islamic art. The images appear to be on the verge of breaking out of the frame, giving them as much of a sculptural presence as her subsequent three dimensional forms.

There is an ever more prevalent questioning of space occurring, and a challenge to the masculine tradition of a definite, hard edged totality of field of vision. In Choucair’s case, fragments have been statically assembled but, pulsate with a compressed energy that hints at the potential for rearrangement. They tease us in and out of the space, in a way that foreshadows the works of Cecily Brown’s writhing forms, so that no definitive narrative or conclusion can be reached.

Similarly, it seems as if her painterly experience of space is translated into the realm of sculpture, creating works with a powerful image as well as deeply sculptural sensitivity. It is this that engenders an intimacy different from the minimalist tradition which, at first glance, you might presume she is channelling.

They appear rather as a fascinating marriage of middle-eastern depiction of patterns and geometry and western Modern figuration, giving rise to a particularly engaging dialogue between the two.

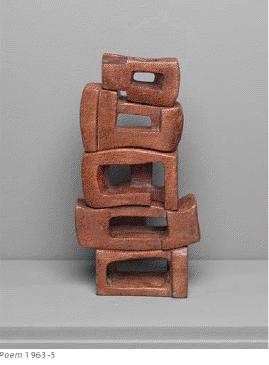

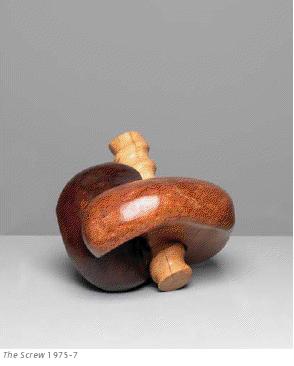

In her Duals series, her awareness of the tonal qualities of materials lend itself to the creation of beautifully realised sculptural works, which sit nestled within each other- much as in the language of Hepworth or Moore. Her poem series also function as stand-alone pieces, or as a group, and have different permutations  depending on preference, offering surprising realisations of negative space.

depending on preference, offering surprising realisations of negative space.

“Sculpture with 1000 Pieces” has a mysterious, magnetic quality. Again Brown’s method of drawing the viewer in and out of surfaces, never resolving into a clean, closed circuit, is evoked. Instead, there is a labyrinthine quality to the work, a fractal multiplication of possibility which messes with a perfect edge. The work opens up and into itself, and it is impossible to say where it ends.

It is interesting in light of this that in the exhibition in the United States the sculptures were displayed claustrophobically crammed within a purpose-built structure within the gallery, forcing the viewer into personal interaction with the work and heightening Choucair’s constant testing of the limits of space.

Her serious gaze, nevertheless, follows you on the way out- the exhibition has come full circle.

This seems, however, to be part of a natural cycle of the artist’s individual perception interweaving with the created forms- as if to remind us that it is her unique position as an outsider that has allowed the structures to develop – rather than the over-stipulation of an omnipotent artist.

Yes she haunts you, but as a construct as well as constructor of the exhibits- somehow a new language of untranslatable materiality is being spoken that is as nebulous as the artist herself. Yet, would completely understanding the work take away the mystery, and leave us with something somehow less special?

All about Choucair, this is an article about the artist Choucair. Lebanese artist Choucair was a fine artist.

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Tate Modern

17 April – 20 October 2013

For further Information and to book tickets visit the Tate website here