[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap] Mars a day….

It’s all about the red planet this week. After yesterday’s report from Louisiana about volcanic activity on a region of our closest celestial neighbour, today’s story comes from the hidden depths of a Yorkshire saltmine.

Searching for life deep below the bed of the North Sea is about the best approximation of conditions on Mars, it seems. A hostile, forbidding environment, devoid of earthly comforts, precious little in the way of atmosphere and the only apparent life to be found is in the microbes.

You can do your own punchline, yeah?

A PhD student from the University of Leicester is helping to shed light on life on Mars by exploring similar environments on Earth — including an underground salt mine in North Yorkshire.

In 2020, the ExoMars rover will be launched on an approximately 7 month journey to Mars. The rover will carry a suite of complex, analytical instruments that will be used to investigate the composition and structure of material recovered from the near sub-surface.

The University of Leicester — working with the UK Space Agency, the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and e2v — is responsible for the development of a camera system for one of the analytical instruments — a device called the Raman Laser Spectrometer, which will be used to investigate the geology of the planet and to search for signs of extinct or extant life.

Peter Edwards, a PhD student from the University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, is part of a team of researchers at the University of Leicester currently investigating how to optimise the performance of the camera by studying various types of samples, recovered from extreme environments on Earth.

Peter’s research involves preparing for the operation of the instrument by looking at the information obtained from previous Mars rovers (such as Curiosity) and determining the best way to operate the detector system that is being developed for the spectrometer.

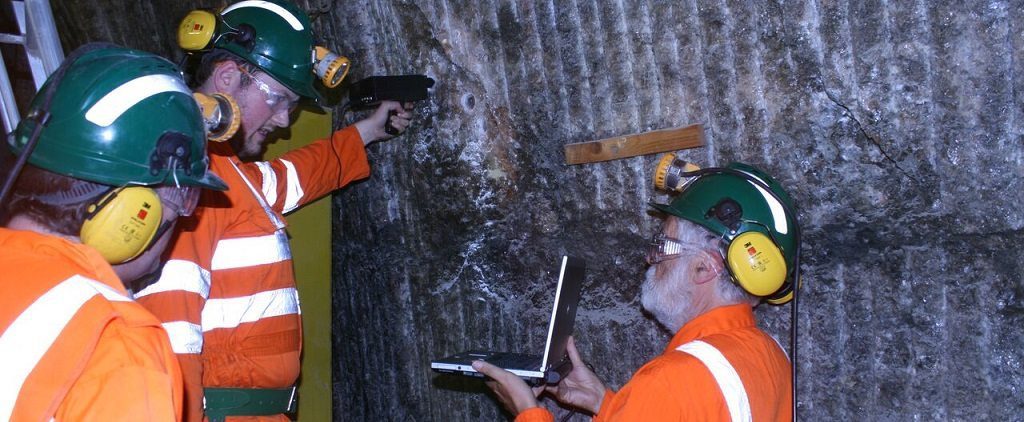

As part of this research, Peter has travelled to North Yorkshire to explore the Boulby salt mine, which stretches a kilometre down and out under the North Sea.

Peter explained: “Parts of Mars are quite similar to the salty environment deep underground at Boulby. In these areas we see polygons marked out in the ground similar in some ways to the Giants Causeway on Mars. Underground we can see these same polygons on the ceiling and walls of tunnels.

“Salty environments are typically hostile to life but certain types of micro-organisms can adapt to these hostile conditions, we call these halophiles. By investigating the difference between the dark outer edges of these polygons compared with the lighter inside we can work out where to direct rovers on Mars when searching for life in these similar conditions.

“Further work with the data from the mine and samples recovered from the mine will allow us to investigate them in much greater detail helping us to plan the targets for future missions to Mars.”

In previous research, a portable Raman spectrometer, similar to the ExoMars prototype, was used to investigate these polygons, observing a significant difference between the two sample types.

When a laser is used to illuminate a target sample, most of the light that scatters back will be the same colour or wavelength as the incident laser light.

However, a very small fraction of the light that is scattered has a different wavelength or colour — this is called the Raman effect.

This colour change carries information about the molecules present in the sample. By blocking out the laser’s wavelength and recording the remaining light using a camera, a ‘fingerprint’ of the target material is obtained.

The information contained within the ‘fingerprint’ can provide information about the mineral content of the sample, or the presence of more complex biomarkers — that may have been left behind by processes associated with life.

One example of this is cyanobacteria, a microorganism which has adapted to ultraviolet radiation by producing a pigment called Scytonemin.

Peter added: “Using this type of instrument, we can readily detect the Raman signature of the Scytonemin and thereby infer that something has lived on the sample at some point.”

Source: AAS.Org/University of Leicester

Image: Charles Cockell

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.