[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]R[/dropcap]ainmaker, the only contemporary Native American art gallery in the UK, has collaborated with the Native American Indian artist Sarah Sense and a Project Curator of the British Museum, Dr Max Carocci, to bring together the exhibition Weaving Water in Bristol.

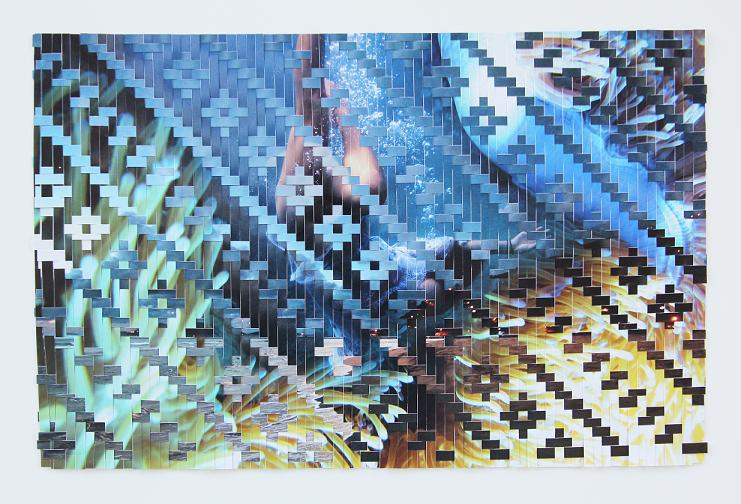

The work combines traditional weaving with photography.

This exhibition explores the notions of both forced and chosen migration, and the impact this has had on culture and one’s sense of identity or feelings of belonging. Both communal and personal issues are suggested in this project, which is centred the on sweeping movement of people from continent to continent. In particular, the personal aspects of the work are manifest in the artist’s concentration on the migration and movement of her own tribe, the Chitimacha, from colonial times to the present day.

During her research for Weaving Water, Sense discovered that the French took her tribal ancestors as slaves to the Caribbean colonies (before the African slave trade was started). This is a new discovery for many because this reverse slave-trading route has been written out of history. Dr Carocci researched into this forgotten history and edited the book Native American Adoption, Captivity and Slavery in Changing Contexts and the film Written out of History.

Prompted by these newfound connections, Sense travelled through islands of the Caribbean and across Southeast Asia to trace her ancestors’ journeys, and the evolution or dissolution of craft skills specific to her tribe and other indigenous communities. In light of this poignant discovery, Weaving Water is an important exhibition, especially for an old port town such as Bristol with a past dealing in the slave trade

Jo Prince, the founder and owner of Rainmaker, describes the exhibition as an ‘outreach’, aiming to reach a wide audience across Bristol. This has been achieved by the exhibition literally migrating across Bristol, occupying three different venues in contrasting areas of the city – Philadelphia Street, Rainmaker, and The Parlour Show Rooms. She has found it energising to find so many different people interested in Sense’s work and Native American art.

With a BFA at California State University, and a further MFA from Parsons in New York, Sense has had quite a privileged education in comparison to some of the Native American artists Jo Prince has worked with in the past. Prince said that this made the collaborative effort quite different to previous experience.

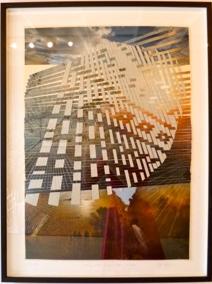

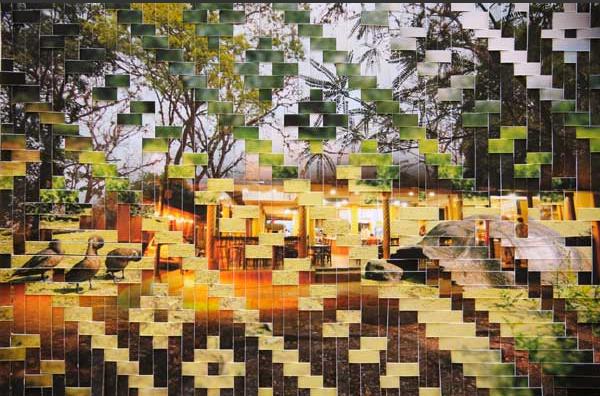

Sense combines two very different techniques in order to make her innovative work. She translates traditional Chitimacha weaving patterns – that are normally used for basket making – and combines these patterns into her photography. Many of her pieces weave together photographs and bamboo paper, the traditional medium for baskets. Within the Chitimacha tribe, different patterns mean different things. Sense has left these patterns intact within her work, so it is easy to spot shapes such as those called ‘worm tracks’, ‘rabbit’s foot’, and ‘raven’s eye’.

[quote]Photography in

Weaving Water acts

as a political statement,

and stands for the

social and technological

integration of different

cultures[/quote]

Sense’s work is striking for the way she so successfully combines the old and the new, the past and the present, and visual or recorded documentary with the oral. This is in terms of both the media she uses and the history she draws upon. She connects with the ancient, oral tribal tradition, and adds photography, a medium very much associated with technological advancement and the rise of modernism. These themes, forms and media echo and mirror each other.

The photographs are composite and there are several horizon lines in each piece. Sense merges landscapes from different points on her travels, which gestures towards the idea that a memory or journey is never static or monolithic, rather it is always a compilation of different angles, viewpoints and places. For example, the piece ‘Weaving Water 8’ has the caption ‘Chile, Thailand, Puerto Rico’ indicating how it encapsulates a wide range of memories and movements.

This idea and technique suggests that Sense’s work is not just recording an event, feeling or known landscape, but is making something new. She is adding herself into the journey, into the history of her ancestral tribe as well as into many different locations around the world. Her work explores existing connections between cultures and makes new ones. This is also encapsulated in the detailed and thoughtful way she has sourced and located her media. For example, she bought – and even helped make – some of her paper from Thailand, and had the photographs printed in another country.

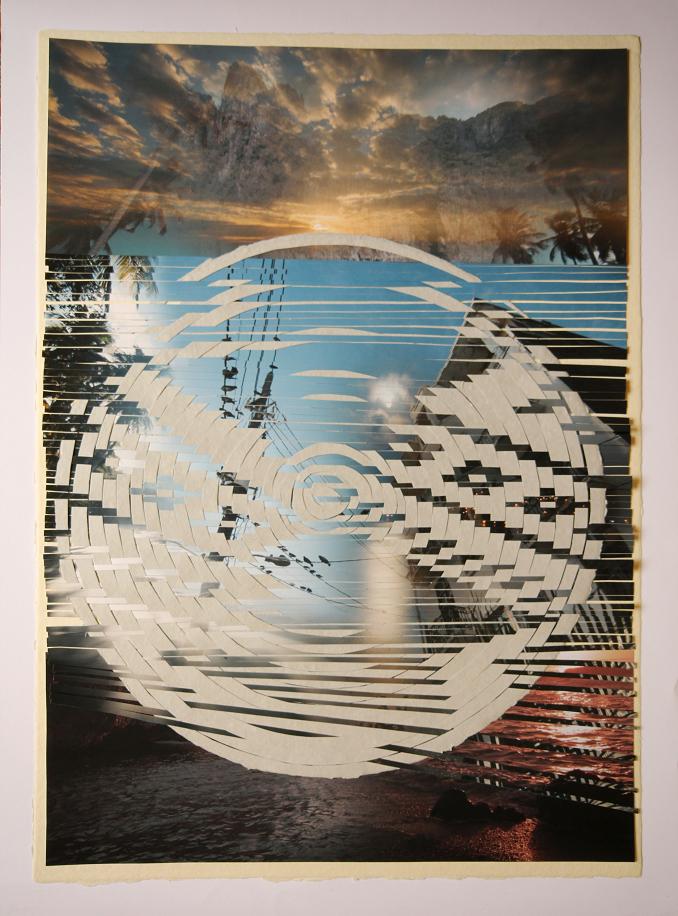

The different viewpoints and landscapes within each piece show several sources of light, such as from the sun and moon. Sense said in her work “the circles are about the sun and moon”, though she was open to the interpretation of them looking like water ripples too. The notions of weaving and migrating definitely lend themselves to being thought about in terms of water, where migrating people travel through the ocean and respond to the ebb and flow of tides. The movement of water is particularly apt as a symbolic force that carves paths, connects landmasses, and shapes landscapes.

Sense uses weave patterns as both distinguished and fully formed shapes and as looser, fragmented forms. This suggests on one hand the dissolution of culture and craft, as well as a sense of it having permanence in Native American culture. The fragmentation of the patterns also alludes to the journeying outwards from one’s origins and traditions, and subsequent merging with other cultures, identities and experiences. In this way, the varying weave patterns combine different states of being.

Weaving patterns are fundamentally caught up in the creation of identity. Spiral shapes are dominant. For the Chitimacha tribe, they symbolise outward movement and growth, beginning with the origin of ancestors and spiraling out into the future generations. Circles are also a repeated shape, which relate to the moon and indicate that no matter where you are in the world you can still look up and see the same moon. Positive connections, rather than dissolutions, are what Sense ultimately draws upon.

These framed pieces of work are set against backdrops of bold wallpaper to create an installation that fills the whole of the space. Having wallpaper as the background links to the idea that the exhibition space is a ‘domestic’ one as it is called ‘The Parlour Show Rooms’. Each wall is different; the back wall is covered in an assortment of English trees, while the large adjacent wall has a more abstract French patterning. Sense thought the pixilated pattern of the French-looking wallpaper was very reminiscent of the weaving patterns of her Native American tribe. Another example of the continual overlaps and connections made within her work.

It is poignant to have Sense’s work displayed on top of a backdrop of colonial culture. The bold wallpaper almost seems to engulf and overwhelm the artwork. The political analogy is obvious.

Long strands of found maps which Sense collected during her time in Bristol are spread across the wallpaper, adding a third dimension to this installation. The maps suggest the spreading out of people through the process of migration, as well as the enveloping conquest of colonial nations. It also shows the way Native Americans were scattered across the globe.

Sense admits herself that her work is very conceptual. Photography in Weaving Water acts as a political statement, and stands for the social and technological integration of different cultures. However, she states that the actual physical making of the work is all determined by aesthetic decisions. She describes herself as a colourist and her photography as paintings.

Despite using traditional weaving for political ends, Sense said she had had much positive feedback from the Chitimacha tribal elders. People viewing the exhibition in Bristol have also been full of praise. Many considered Weaving Water the best thing they have seen at The Parlour Show Rooms – and this is a place that can host a different show each week. A lot of work passes through here.

For years Sense has been applying to learn the true weaving of the Chitimacha tribe. She has just heard that she has now been accepted to begin this next journey. An achievement, and a turning point. She will be the youngest weaver by about thirty years. Sense admits she is not sure where it will take her.

Weaving Water opens in Denver, Colorado and in Tulsa, Oklahoma this autumn.

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby