[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]G[/dropcap]iven the still-increasing popularity of sound and installation art, the National Gallery’s Soundscapes project seems so obvious it’s perhaps surprising it’s only happening now.

Six very different musicians/sound artists/composers each select a work from the National’s collection and create a soundtrack to accompany it. The works are each presented in a separate room, allowing plenty of physical space for the sound to unfold around it and for the audience to move around (and in some cases) lie down in.

The most recent paintings featured are from 1905 and the oldest, The Wilton Diptych, dates from c. 1395. Before viewing the rooms, visitors watch a video featuring the curators and the soundtrack creators discussing their choices and the approach they took.

The first of these is the Radio 4 favourite, respected sound recordist/artist and Hafler Trio/Cabaret Voltaire veteran, Chris Watson.

He engages with Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s 1905 Finnish landscape Lake Keitele from a distance, producing a 50 minute soundtrack from lakeside and forest recordings taken around Kielder Water in Northumberland. Transposing the Northumberland sounds onto a Finnish summer landscape creates a contradiction that at times is quite apparent, especially as in the video he discusses the way in which the sounds of the specific environment will have impressed themselves on the painter and painting. Even the ways in which sound travels will be very different in the climactic conditions of the two lakeside environments.

Since the canvas itself is fairly small you have to approach pretty closely to really enter the landscape it depicts. The soundscape is varied and at times synchronises well with viewing the painting, for instance when hearing bird calls and watching the lake. At other times it drifts away from the painting into a detached soundscape that might have worked better in a more fully darkened room without the painting. It might also have benefitted from being slightly louder.

The work also suffers from being located by the entrance, with entering visitors breaking the spell as they try to get close to the small canvas. Watson claims he wanted to do more than soundtrack the specific painting, hoping that visitors will imagine what other paintings in the National’s collection might sound like and “to tune into themselves.” Despite its contradictions it’s an interesting experiment and a good scene-setter for the rest of the show.

Leaving the first room and turning down a dark corridor, you enter a more mysterious space. At the back of a long room sits Hans Holbein the Younger’s cryptic The Ambassadors.

Hans Holbein the Younger Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve (‘The Ambassadors’) 1533 © The National Gallery, London

Set in this modern space and accompanied by Tate Prize winner Susan Philipsz’s sparse soundscape, the 1533 painting seems contemporary. The remarkable three-dimensional skull at the foot of the picture seems even stranger in this atmospheric context. Philipsz took another small detail of the photo, the lute with a broken string as a source of inspiration for the hesitant but hypnotic violin sounds she uses to create Air on A Broken String. She wanted to draw out the underlying tension in the painting, which she relates partly to the fact that one ambassador represents state power and one church power.

Here the interpretation is not just sonic but art historical – new modes of interpretation are opened up through the attempt to apply sound to/derive sound from the painting. The result is certainly effective. Get close enough to the uncanny details of the image and and it almost seems like you’re watching a very slow video installation. Apparently some visitors have been lie in front of the painting for long periods.

The way in which the show gives people the chance to experience historic paintings in a more informal, installational way is really interesting and seems worth developing further. The only drawback is the perpetual curse of sound art in spaces that haven’t been designed for it (or not sufficiently modified to host it) – occasional distracting sonic bleed from neighbouring installations.

How you first encounter Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s Conversation with Antonello will depend on when you enter it. The light in the room waxes and wanes in a simulation of day and night outside a model reconstruction of Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study (c. 1475). Besides the light what you first notice are the diorama scenes (rivers and hills with small figures) arranged behind the model of the study. Both these and the main model have crude wooden exteriors, there’s no attempt to disguise the staginess of the installation. The totality of the installation makes sense only when you approach the model study and look through the hall that surrounds it.

Here the river and the hills beyond are visible through the rear windows of the model hall. The shadows within the structure and on the landscape change gradually and effectively as each “day” passes, with a beautiful light falling on the river towards the virtual sunset.

As with Chris Watson’s piece, the soundscape isn’t based on recordings taken “on location”. In this sense it both convinces and frustrates. It sounds plausibly pre-modern but not specifically Italian, what we hear isn’t a precise simulation (let alone documentation) of how such sounds would travel in such an Italian landscape, either now or then. However, the mix of domestic and distant sounds does function well.

We hear birdsong, flowing water, footsteps, horses, work in the fields and also a melancholic singer moving around the hall surrounding Jerome’s study. The way the light changes within the hall is powerful and more effective than on the dioramas, particularly the lengthening and shortening shadows cast by the pillars. The long perspective of the hall is really impressive, allowing you to see the structure within the painting from sideways on and in a fuller (and more poetic) spatial context.

Nico Muhly’s Long Phrases for The Wilton Diptych takes on the evocative portable altarpiece designed for Richard II (c. 1395-9). It sits behind glass in the centre of a large dark room with high ceilings. Here there is a chance both to move freely around the space and experience the shifting sound and to get very close to to the work, to study the colours and ancient paintwork and its royal-religious symbolism, including Richard’s iconic emblem: a chained white hart with a crown around its neck. The work is a collaboration with viola da gamba player Liam Byrne and sound designer Jethro Cooke.

English or French (?) The Wilton Diptych about 1395-9 © The National Gallery, London

The American composer’s soundtrack addresses each panel in turn. This room is also affected by sounds from neighbouring installations and yet with the skillful lighting there’s an austere and fragile atmosphere in the room. The music seems to fulfill some of the roles the original, unknown painter(s) would have – providing sonic decoration in an affirmative way but also alluding to the passage of time and powers beyond the worldly. At times the music seems a little too light, too prettily post-minimalist, suggestive (perhaps deliberately) of a royal courtier/artist eager to please their royal patron. Yet there are more austere and sober moments that work more powerfully, bringing out the great age and mystery of the original work. Its shifting moods illustrate the varying functions the visual scenes were and are supposed to fulfill and leave space for contemplation.

Moving forward the best part of a millenium we reach Cézanne’s fin-dè-siecle Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), soundtrack by award-winning film composer Gabriel Yared. His music feels the most contemporaneous with the painting of all the pieces. It’s often very delicate, in the tradition of French musical romanticism. The four minute piece is arranged for soprano, cello, clarinet and piano (played by the composer), each assigned one of the speakers. The audience are encouraged to move between them, mixing the sound according to taste although the effect is more subtle than dramatic. In its more abstract moments it does succeed in making the painting seem (even) more fluid and hallucinatory, so while it could initially seem like one of the most directly accessible (and in a way populist) pieces, it does bring out some interesting undercurrents.

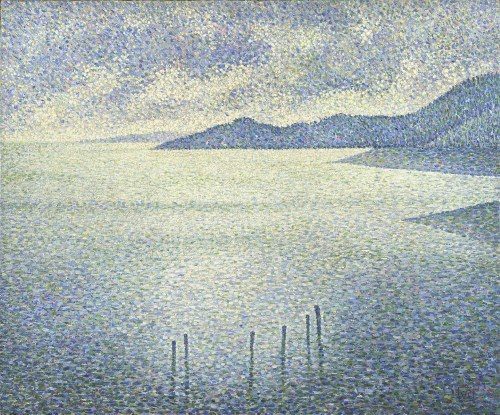

The most populist choice in the show is surely Jamie xx of The xx. In the introductory video he is spoken for by others, seen only at work on his laptop. The installational arrangement relies on the directional speakers – the piece is heard most completely at distance. The closer the listener comes to the painting the more the sound breaks up in an attempt to complement the pointillist techniques of Théo van Rysselberghe’s Coastal Scene (c. 1892). The sounds are mostly bright and affirmative, summery in tone, but the lighting in the room emphasises a hazy-heaviness and stillness in the painting that seems at odds with the tone and pace of the sounds.

Théo van Rysselberghe Coastal Scene about 1892 © The National Gallery, London

With works chosen by such varied individuals there’s no overall coherence to the show and it perhaps has a slightly naïve aspect when compared to other sound/art shows. There are some similarities in technique and staging between the rooms it inevitably has an episodic quality and it’s hard to see it fully pleasing either the more adventurous of the National’s more traditional audience or those seeking radical artistic experimentation. There’s probably only minimal crossover between the audiences of the sound artists represented, so if nothing else the show is likely to draw extremely diverse audiences (which in some sense is a key goal of all major art institutions). Ultimately it’s a semi-successful but still worthwhile venture with some very powerful moments.

Soundscapes

National Gallery

8 July – 6 September 2015

From Speak and Spell to Laibach.