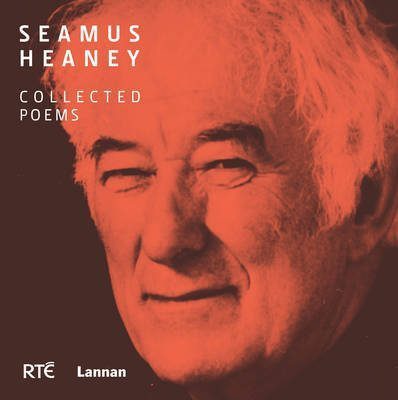

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap]lthough the family of Seamus Heaney have released no details of funeral arrangements yet, it is hard to imagine anything other than burial for this most grounded of poets.

Talking heads will talk. Friends, rivals and enemies will bluster and dissemble for news and late-night arts shows about politicisation and colonialism, trochees and analogies, about a poet who swerved away from the troubled violence of his native land only to transpose the brutal squabbles of the ancients instead. What happened on the surface was never enough for Heaney. Too fleeting, too close.

Instead, the techniques of archaeology informed the poet. Where his (near) contemporary Patrick Kavanagh assigned importance to the pastoral by invoking Homer:

….Which

Was more important? I inclined

To lose my faith in Ballyrush and Gortin

Till Homer’s ghost came whispering to my mind.

He said: I made the Iliad from such

A local row.

Gods make their own importance.

(From ‘Epic’)

Heaney took a more oblique approach, casting the grim affairs of post-partition Ireland as the petty squabbles of a more universal and eternal tendency to violence, to brutality and to survivalism in human nature. Beneath the surface, as Heaney told it, were the prehistoric victims of ritual sacrifice in Danish bogs; were Beowulf and Grendel; Achilles and Hector – an eternity of petty squabbles only of importance to those living through them.

And it was comforting.

If Heaney’s living legacy as a poet can be reduced to one observation, it was that there was a bigger picture. Far from nihilistic or defeatist, Heaney evoked and expressed the continuum of survival and progression. In ‘Digging’ (perhaps as essential a work in verse to the Irish schoolchild as Wordsworth’s ‘Daffodils’ is to the British equivalent) Heaney reflects upon the progression (or descent) of generations of Heaneys tilling the soil. The line comes eventually to him, no longer digging, but writing.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

And dig he did. Past the short-term skirmishes, the whining and the poor-mouth political egocentrism of many of his contemporaries in poetry, and toward the universal. Daunted but never cowed by those who preceded him, (whether agricultural or literary) Heaney acknowledged without egotism his own place in the roll-call of Irish writers. In his 1984 dream narrative Station Island Heaney consults with those monoliths of Irish and international culture and comes out with a deserved swagger. ‘Let go, Let fly’, Joyce tells him.

To have done so whilst remaining so firmly planted in the soil of his native Toomebridge took versatility, erudition, a lightness of technique and an imagination broader than the average. The staple stuff of poets, one might dismiss, but all balanced in Heaney’s case with an approachability and a joy in the ability of poetry to ascend the quotidian. Few Nobel laureates make visits to state schools to discuss poetry. Heaney did, and will be remembered by many as a somewhat uncomfortable-looking figure, as terrified of the head-teacher as they were themselves, only to burst with hearty laughter at some small prompting.

This piece must end before it becomes a eulogy of some imagined Gandalf-figure, blowing poetic smoke-rings thought the stuffy confines of academia when not riding a Nobel-sponsored eagle over Schliemmann’s Troy. Let it be in his own words instead:

Your obligation

Is not discharged by any common rite.

What you must do must be done on your own

So get back in harness. The main thing is to write

For the joy of it. Cultivate a work-lust

That imagines its haven like your hands at night

dreaming the sun in the sunspot of a breast.

You are fasted now, light-headed, dangerous.

Take off from here.

(From Station Island)

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.