Embedded within our individual experience of life is the notion of consumption and presence, by which the parameters of human experience can be constructed (as much as it could be disrupted). In the artistic realm, how do we determine if art’s potential is limited to being a calculated representation of existence versus its transformative social capabilities through becoming an experiential by-product of expression and society? Can art nurture attentiveness, empathy, and introspection by recalibrating our relationship with visual culture and urban environments?

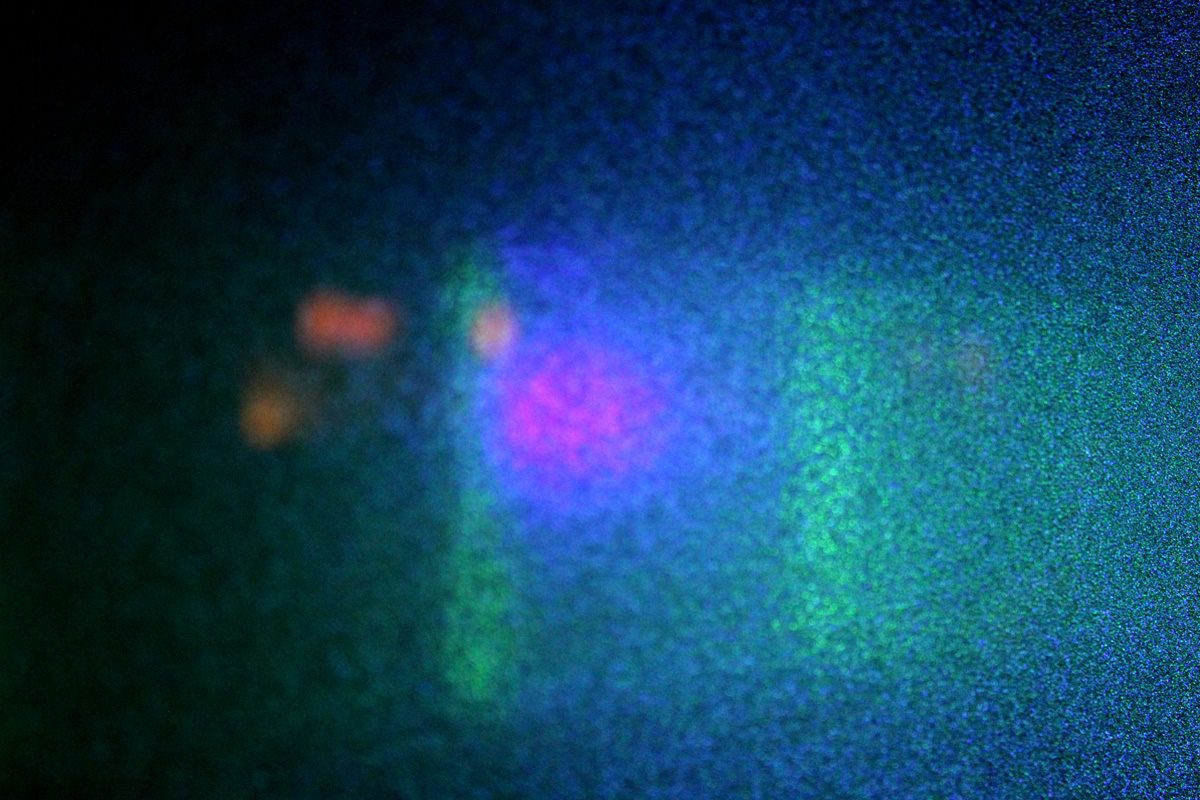

From 1st March to 9th April 2023, landscape architect and artist Jean Francois Krebs took over the Smallest Gallery in Soho to investigate the intimacy between the intersection of society and the human experience. Shining an incandescent blue light on the emotional spectrum induced through how we engage with our environment and the trepidation that arises when we dissect the connection between the individual and society, Krebs’s site-specific installation, Septuplet, is a gentle and covert artwork that fuses art with incidence, synchronicity, and observation. Nestled into London’s cultural history, Krebs’s artwork transforms philosophical concepts into tangible material, challenging the relationship between perception and environment through his fleeting light display, creating a polarity between being immersed within one’s environment and the intrinsic value of the ability to be authentically present.

Rooted amongst a convoluted mesh of London’s foundational energy of ‘capitalist-meets-kitsch-subculture’, Kreb’s work can be found in the heart of Soho, exhaling an enigmatic breath of life onto the stale souvenir and erotic shops running adjacent from the display. As out of place as a punk looks at a football match, Septuplet can only be viewed externally, adorning the grey and gridded window display of The Smallest Gallery in Soho’s Victorian building, either as an entirely blacked-out window or a blue haze appearing in intervals of one hour, disrupted by fifteen minutes where the lights go off. Septuplet’s blue light permeates across the window into aqueous shades of green, with the light fragmented into a crystalline structure perforated against the lubricated outer glass panes.

Alongside the artwork’s spectral ambience, its temporal quality juxtaposes unattainability and a sense of being blessed with the chance to encounter a natural phenomenon. Cyclical and awkwardly linear, the time-based element of Septuplet embodies a poetic twilight zone and essence of haphazardly meandering through life’s labyrinth of an innocuously humdrum existence – a commonplace reality for the timeline of life in a capitalist society.

Tackling how society co-habits and engages with space, the artwork utilises materiality and composition to prompt its viewers to question the political and existential qualities of our built environment, fused with the dualism between human-urban embodiment. Elemental in its aesthetic – the work interweaves the appearance of viewing into the eerie depths of the ocean or visually tracing the periphery of the Northern Lights. Yet, although radiant in its rays, the meaning behind its glow is more deceitful than it is blissful; behind the barricades of the outer glass window display, the artist has carefully installed seven panes of uranium glass, delineating a destructive paradox of Western commodification and appropriation of Earthly materials and the human desire to objects that are of perceivable beauty and allure. Uranium triggers ideas of warfare and technological production, demonstrating the tendency to overwrite the authentic existence of a natural source with its human-given function.

Unravelling Septuplet’s conceptual roots, this perspective illuminates the human tendency to have binaristic interpretations of life experiences, where perhaps the artwork invites the viewer to be actively aware of the mental transactions that take place at the cross-road of our environment and thought processes. Expanding on the role of dualism within Septuplet, the installation places the uranium in the gallery’s interior display, drawing attention to the distinction between how we base our analysis on the outside and the comprehendible element of the artwork.

This opens up a dialogue between the internal and the external by demonstrating how we form opinions based on our initial observation rather than comprehending the underlying substance behind how we analyse our visual stimuli. However, contemplating this parallels the beauty of subjectivity within the human experience and how art can enrich our lives. For the artist, Septuplet uses the seven uranium glass panes to explore the concept of seven siblings, connected by the intangible notion of existing in the same womb, highlighting ethereal plateaus of lived experience that is so incomprehensible yet universal to all of life.

Delving into the genre of site-specific art, Septuplet intercepts the infinite flow of visual media that embraces the street of this corporate, yet admittedly charming, haven. Site-specific artwork does not only entangle the viewer in a sensorial myriad of art objects but also into the work’s physical environment, holding space for the surroundings to co-author the artwork. This relationship could occur through positioning artwork within an area with socio-political or environmental connotations or by focusing on the experiential encounters that enrich our lives, day in and day out, such as through a space’s natural scent or acoustic value.

This element of the artwork transforms Soho into an existential body: the installation creates a dichotomy between the response mechanisms of individuals in society – with the ever-saturated urban environments, encapsulating how our visual experiences shape culture through subliminal association with our environment. Existing inside London’s skyline, architecture plays an intrinsic role in the concepts behind Septuplet. Dancing to the siren-riddled beat of London’s drum, Septuplet illustrates the metaphorical idea of a concrete jungle. Do the historical and cultural narratives imbued into London’s architecture personify Soho’s landscape enough to cultivate a sense of architectural sentience?

The exhibition kindles societal introspection by blurring the boundaries between the artwork and the exhibition’s surroundings, shadowing the existence of the society living within it. By exploring concepts such as Eco-psychology, we already know from research surrounding being immersed in nature that the relationship between the human psyche and one’s environment plays a foundational role in the restoration and wellness of society.

Psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan coined an area of research called ‘Attention Restoration Theory’ (A.R.T), which theorised that happiness, concentration and clarity are all heightened after exposure to nature. Although Septuplet encourages urban immersion, the principles of A.R.T delineate the soft power behind how we engage with urban architecture. In simple terms, the Kaplan duo explored the dynamic between attention and restoration. They found that exposure to nature culminated in a recalibration of one’s mindset and happiness. They researched this by pinpointing four avenues for mental rejuvenation that can be achieved through engaging with your environment: being away, fascination, extent and compatibility. Although all four categories form a vibrant eco-system that fully flourishes when working in dualism, the notion of ‘being away’ and ‘fascination’ gently illuminate Septuplet’s power.

Working together, the concept of ‘being away’ and ‘fascination’ act in coalition to create a sense of peaceful escapism from the constraints of ordinary life by creating a distraction and replacing it with gentle and easy entertainment. In some ways, this relates back to the significance of being present and existing mindfully, which opens up the opportunity for radical and deep contemplation, allowing the viewer to appreciate the correlation between their surroundings and how that can prosper a more fulfilling experience. Although this research applies to natural environments, Septuplet could be nurturing this perspective by mediating the hectic nature of urban environments with a moment of calm and stillness.

Deconstructing the site-specific element of the artwork could bring attention to how the nature of existence within London’s capitalist essence is political; the city’s urban landscape overflows with hierarchical constructs. Much like the exploration of materiality within the visual arts, the nature of architecture and its connection to social and economic stability helps the artwork to articulate controversial yet poignant themes within it when viewed from the perspective of being a site-specific piece of art.

A road sign reading ‘resident permit holders only’ accompanies the work, opening up dialogues surrounding how we engage with space in the perspective of fleeting observation versus security and permanence. The concept of residence and permission in architecture entangles its viewer in an ethical web of how one inhabits the right to exist. The sign could be interpreted as saying that the viewer has temporary access to spatial engagement, which subverts the viewer’s role in the Septuplet by categorising them as strictly existing as a spectator, transforming the viewer into a performative element of the site-specific artwork. Could this reinforce the idea that the viewer’s existence is a commodity, where their interaction with the environment is transactional? In the book ‘Society of the Spectacle’ by Guy Dubord, the author reframes the individuals’ relationship within society as almost being contractual, whereby the people within society exist solely in conjunction with commodities, reducing people to living to consume commodifiable products, such as media, as well as material products and intangible goods.

Applying this concept to Septuplet creates a conflict between the idea of freedom with systemic authority, simultaneously transforming the existence of the art and the viewer into existing as a commodity without autonomy. The graffiti and posters surrounding the gallery space could also amplify these tensions by representing how the context of permission within art could enable it to become commodifiable. These concepts echo Henri Lefebre’s philosophies on the theory of space, delineating how our conception and allocation of rights to a location is inherently political and deeply tied to social class. Lefebre’s research explores how the division of space disproportionately benefits the rich from how architectural space is distributed to support consumerist relationships with society and architecture, where income creates accessibility to privatised and profitable spaces. Summarised eloquently by Stuart Elden in his article ‘There is a Politics of Space because Space is Political: Henri Lefebvre and the Production of Space’ written in 2007:

‘Lefebre’s notion of everyday life suggests that capitalism, which has always organised the working life, has greatly expanded its control over the private life, over leisure. This is often through an organisation of space’.

Despite being orientated around urban communities, these concepts could also represent a microcosm of global politics of space and colonial power, such as how marginalised countries throughout the Global South are deeply intertwined with inequality through exposure to environmental devastation and overpopulated countries which lack resources.

Another approach to how Septuplet encourages its viewers to engage with space aligns with architect Louis Kahn who explores the philosophy of architecture through his research into the psychology of the void. Relating to the concepts of A.R.T, he discusses how negative space within architectural space provides a peaceful oasis devoid of distraction, creating space for deeper interactions with one’s environment. The stillness and thought-provoking nature of Septuplet’s installation perhaps embody this role, disrupting London’s overwhelming nature by sculpting a reflective void into the city’s architecture. A quote from the book The Architect’s Apprentice by Elif Shafak enhances these concepts by illustrating a spiritual relation to the human-architectural connection:

‘Alone in the mosque, only a dot in this vast expanse, Jahan could only think of the world as an enormous building site. While the master and the apprentices had been raising this mosque, the universe had been constructing their fate. Never before had he thought of God as an architect.’

The beauty behind site-specific artwork is that its subjectivity represents how art can cause social change by simultaneously interrogating many discourses. Septuplet interrupts the act of meandering through a hectic urban environment interconnected with consumerism by subverting the paradox of the citizen being a commodifiable bystander dictated by their ability to purchase and consume; the artwork liberates the viewer from this dynamic, nurturing critical introspection and forging a path for compassionate consideration of social dynamics and open-mindedness. Could Septuplet depict how art can metamorphose a utopian society by recalibrating our engagement with environments into one entangled with radical sympathy for one another and underlying social hierarchies systematically imbued into our surroundings?

The exhibition was be on display at The Smallest Gallery in Soho until 9th of April, 62 Dean Street, London, W1D 4QF.

THE Smallest Gallery In Soho

62 Dean Street, London, W1D 4QF

February – 9th April 2023

Curated by Olga Tarasova

As a multi-disciplinary artist, my work creates a dichotomy between the consumable quality of the manufactured and the delicate nature of the hand-built as a radical pursuit. Fusing this with my contemplative nature, my work delves into the comfort of the polarity within various discourses. Responding to my personal artistic explorations and the ever-evolving narratives within the art realm, my writing delves into theways that art interweaves socio-political commentary, ecology and philosophy with fictitious speculation.