Over his 35-year career, plants and animals have played a pivotal part in the work of Shimabuku (born 1969 in Kobe, Japan. Full name Michihiro Shimabuku). To date, fish, octopi, monkeys, flowers, citrus fruit, cucumbers and even potatoes have been recruited as collaborators in his escapades – journeys or experiments underpinned by an element of poetic or philosophical enquiry, captured in videos, installations and occasionally sculptures.

For example, Shimabuku’s Liverpool Biennial (2006) commission, Fish and Chips, gently ridiculed the British obsession with this food pairing through a blurry, underwater Super8 video depicting an imagined ‘romance’ between a potato and a fish. His particular blend of whimsy and humour goes down well in the UK, he says during a private chat after the opening, and also Italy and France. ‘Not in Germany or America, or Japan. They are too serious.’

For this, his first solo show in Spain, at the Centro Botin, Santander, he has chosen the octopus as his co-star, partly because they are native to this Atlantic coast. But also because they have proved such fruitful co-creators in past works.

We have almost his entire octopus oeuvre here: beginning with an encounter in a Swiss toy shop in 1993, called On the Beach in Zurich. Discovering a cardboard box full of plastic animals, he spent a happy hour on his hands and knees playing with these figures. And then, as a wall caption states: ‘A donkey in the bottom of the box looked at me, so I put it in front of the octopus. Their eyes met, and appeared to have been looking at each other since long time ago.’ That same plastic donkey and octopus are paired here on a plinth under a protective glass case. And they do appear to be locking eyes in a very intense way. Or maybe it’s Shimabuku’s skill in drawing us into his whimsical world that makes the idea somehow plausible.

He soon progressed to live octopi, though had to learn the hard way – after accidentally killing one – how to look after them for extended journeys: the trick is apparently keeping them at a stable temperature, in seawater. He put his newfound skills to good work in: Then, I Decided to Give a Tour of Tokyo to the Octopus from Akashi (2000). The artist started out wondering if an octopus would enjoy an outing to a different part of Japan, as much as he does. The accompanying video shows Shimabuku catching an octopus in Akashi, transporting it (carefully, in a temperature controlled container) by train, to Tokyo. There, he takes it to the Tsukiji fish market, where it attracts admirers, and then Shimabuku transports the octopus safely back to Akashi. ‘I’m glad to see he’s in good shape’ he says in the video, as he lifts the octopus out at the journey’s end. ‘There, he’s going home’, he says, clearly elated, as the octopus sidles into the sea.

Whatever Shimabuku does, there is a joyful naivete to it. He is wholly committed to each unlikely escapade. It makes you want to commit to the experiments too, even when they don’t appear to be going well, such as Catching Octopus with Self-Made Ceramic Pots (2003). He conceived this work for the Albisola Biennial, hoping to revive in Albisola a traditional method of Octopus fishing with ceramic jars still used in Japan. He worked with a local ceramic studio to create the vessels, which he then laid out along ropes, on the seabed. In his video, we watch as he sits in a boat, lifting one after another of these pots out of the sea, all of them empty. Right at the last minute, an octopus is discovered lurking in the bottom. Shimabuku’s euphoria is heartfelt and infectious.

For Going to meet the Octopuses in Santander (2024), Shimabuku brought a variety of glass vessels, some big, some smaller, from Japan and San Francisco; a mixture of transparent and opaque, plain and vibrantly coloured. He hoped their choices would reveal: ‘What kind of octopus is the octopus in Santander?’ In Centro Botin, the vessels he used are now part of the exhibit, laid out on a large, low plinth. On the adjacent screen we see Shimabuku in diving gear, going to inspect them in their underwater setting. He finds many Santander octopi have taken up residence. Some stare balefully at him as he points the camera into the opening; some swim away. But the star of the video is unquestionably the one that suddenly thrusts a tentacled limb out to try and grab the camera off him: we see the suction pads attaching to the lens, then the camera’s movement as he wrestles with the artist, trying to draw him in before finally giving up and thrusting himself away from the scene, with a scornful squirt of black ink.

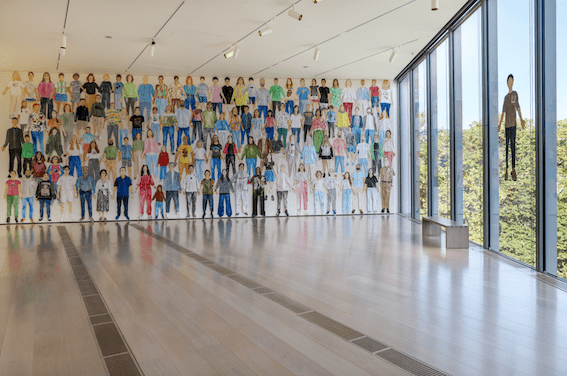

There were two further commissions for Centro Botin. The second, Flying People (Santander) (2024), riffs off a related project he devised in the Austrian Alps (When Sky Was Sea – Flying Me 2002/2006): after discovering that these Alps were once coral reef, millions of years ago, home to fishes whose fossil forms are still embedded in the rock, he worked with a group of schoolkids to make fish-shaped kites. They flew remarkably well, appearing to swim in the air, much as they would have in the prehistoric waters. He also made a kite of himself, and discovered, according to his caption: ‘When I see myself flying in the sky, I feel a sense of elation, almost like courage.’

The treat he cooked up for the folks of Santander: he ran a workshop for locals of all ages to draw life sized pictures of themselves, which were then attached to kite string and filmed floating around the Centro Botin. The same, colourful population is spread out across one wall at the end of the gallery – a rainbow nation of kite people. When the show ends, they get to take their kite figures home, so they can fly whenever they like.

There are definitely shades of the 1950s and 60s Gutai movement in Shimabuku’s work – no surprise, since it emerged from his hometown of Kobe. Formed by Yoshiharo Jiro, and with Yoko Ono among their members, Gutai sought tothe idea was to explode the idea of art as object, as collectible, preferring disruptive events or happenings outside the museum. There is something reminiscent of Ono’s works here, specifically the playful early ones exhibited in her recent Tate Modern show, such as inviting audience participants to bang nails into a canvas to make a painting, or to climb into a black cloth bag to make a human sculpture. For example, Shimabuku places a box of rubber bands on the floor, and invites us pick one out and try and crawl through them. The presence of several broken bands implies that some have indeed tried… and failed; however, as an art work, this one is visually and conceptually underwhelming, as are a few other of Shimabuku’s projects, where the visual representation would be baffling or banal if it weren’t for an accompanying caption.

Asked if the Gutai were an influence, he says: ‘I grew up in Kobe, and that’s the capital of Gutai… but they behaved like teachers. I didn’t like that. (They were) very established. (When) local museum people are saying we are doing something new, that means they are doing a Gutai show. That means no space for me. This is the reason why I went out from the city.’ First, he went to study art in Osaka, graduating in 1990 from the Osaka College of Art, then developed his practice at the Art Institute of San Francisco. He also lived in Berlin for 12 years, from 2004. He now lives in Okinawa.

The driving principle of his work, he says, is: ‘I just want to be amazed. I am just sharing this with people. Each work I am amazed myself. It’s not like a teaching, it’s more like a sharing – my surprise.’ How, after over thirty years of this practice, does he keep the ideas fresh, or maintain this sense of openness and curiosity? His answer is appropriately gnomic: ‘I always say that if I don’t have an idea, idea comes to me. If you have an idea first, idea doesn’t come to you. When you go to restaurant, if you already know you want hamburger that’s all that comes to you. Just keep hopeful. Don’t have ideas. And then: “Ah, this sounds interesting.” You find it.’

For his third Santander commission, he devised a new question and a new co-creator: limes. (There is a site- and person-specific connection here too, though few would know it: the president of Centro Botin, Vicente Todoli, has a citrus farm in his home region of Valencia, and he has supplied all of the fruit used here). At the far end of Shimabuku’s exhibition is a gallery with huge windows looking onto the sea, filled with pristine glass tanks. The work Something that Floats/Something that Sinks (2024) was inspired by an observation that citrus fruit, when placed in water, either sink or float. So he has populated these tanks with limes. True to his observation, some float, others sink. But some of the limes appear to be moving around the tanks. How is that possible? Is there an invisible current activating their movement? Later, Shimabuku admits. ‘Yes, there is a current… But this was a thing… I discovered only when I tried it. It’s really about discovering something.’

Though some works, as mentioned earlier, are more successful or compelling than others, among the best of them there is skill and ingenuity behind their apparent simplicity – the choice of grainy, amateurish and analogue or crystal clear and digital film technology is carefully deployed to conjure the requisite amount of comedy and also wonder. If anything is Shimabuku’s USP, it is his ‘capacity for wonder’, as curator and exhibitions director Barbara Rodrigùez Muñoz remarked on at the opening. But I do find myself ‘wondering’ if you need a critical mass of Shimabuku’s work in order to reach the level of suspended cynicism its childlike simplicity demands. Would any of these works have the same strength, in isolation, or do you need a critical mass? Does it matter? Clearly not to him. He agreed, privately, that his work is hard to monetise: monetising is not the point. In fact that absence of commercial value very much IS the point – the oxygen in which his art works breathe. He also said that ‘collectors don’t like my work. Some people want to have the complete object… And I understand that, so that’s maybe the reason why I am invited to museum shows. I am happy to have a show in a museum. Museum is a good place to be in a show… with many people.’

Other artists working to generate humour through naivete or a disengagement from the rules of commodification, such as Martin Creed, have capitulated as they age, creating series of works that deliver a ‘complete object’ for the collector. There might be potential for the high resolution photographs of octopi embracing Shimabuku’s designed objects to become collectable. They are beautiful images, as well as endearing. But for now his resistance is high – to categorization as well as commodification. At the opening he was asked whether his work could be described as relational art. ‘Animals, plants, people, it comes to me very naturally. Relational art? It’s just how I work. It is a pure pleasure to me.’

SHIMABUKU: Citrus, Octopus, Human is at Centro Botin, Santander.

October 5th 2024 – March 9th 2025.

Arts writer, editor, curator. MSc Environmental Psychology