Annya Sand paints smoky abstract works which contain concrete points. The argument being that where figuration is more open to interpretation, within abstract works the artist can focus on a central feeling, a broader net that when given context captures a sense of action.

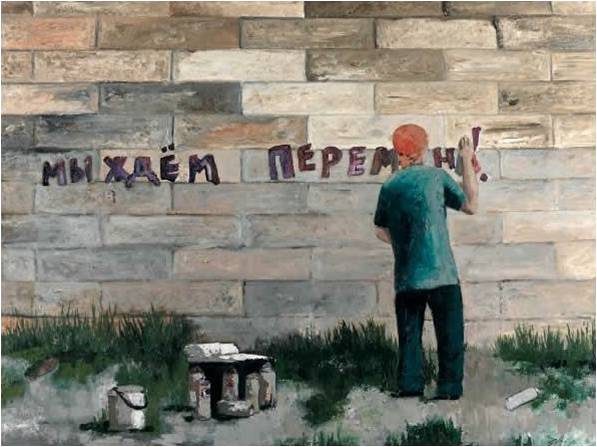

Sand’s earlier work focussed on direct statements, what we might call her externalisation phase, her political statements and perspectives expressed through forms that the viewer can read directly: Russian State symbols, brick walls, graffiti, slogans and decay. Statements that she’s explained in voluble essays on topics such as artists and social media, women in art, and the frontline between commerce and conscience — whether social activism is acceptable in art. It is refreshing that rather than toeing the polite liberal line of ‘whatever’s cool with you (and your chequebook) is fine with me’ she questions why there isn’t more controversial work to mirror our fractured times, and where lines are drawn in seeking recognition.

“The art world is small, and conservative, and exclusive. More often than not, it prefers to play it safe. I lose count of the number of my paintings that have been rejected by galleries who don’t want to be associated with negative discourse or political statements, and I can’t deny that it is frustrating. But I am under no illusion. I must work my way up the ladder of opportunity and respect, just as one would in any other industry.” Annya Sand (2016)

At that stage Sand felt required, internally and externally, to leave behind her ‘black-and-white statement’ art to move towards a more ‘technicolour’ spectrum of political statement. The drive wasn’t to abandon her beliefs but to expand the audience for both her ideas and herself. So that, rather than going for the most obvious statement the same topics could be approached in a variety of presumably more effectively ways. In other articles she’s written about Russia’s soft power initiatives, where the State seeks to combat bad press with cultural largesse. One wonders whether she hasn’t co-opted the same methods in her work.

Sand’s work has most conspicuously been collected by political organisations so the question has to be asked whether she has become an ‘organisation’ artist? Someone who ticks the righteous boxes of bureaucratic spend with attendant assumptions of tangential creativity, bounded by reactionary politics, local vision, or bland discourse. Artists are of course happy to have their work bought and high-profile commissions are not to be sniffed at, but they should be careful when their work is placed in rhetorical contexts over which they have little control. More so since good art rarely says anything completely; it cries that meaning is imminent and pulls its catch towards specific shores. Again the question of internal and external meaning comes into play. It is doubtful whether Sand makes work for her buyers. Her work remains personal and shows signs of development; she hasn’t the glib sheen of a zombie formalist, the marks of a human touch are celebrated in her painting, even if the subject matter is initially aloof.

Sand’s abstract work when viewed as emerging from her previous figurative work are evocations of opaque symbolic motifs that borrow classical palettes and twisted forms to describe self-consciousness, introspection, fear, wonder, hate, and empathy. The artistic draw is just a slip away from expressing how political events affect the spirit towards a more open (though indistinct) expression of internal dialogues. We feel, or so we think, but we don’t know why or what exactly.

Week one – Annya Sand

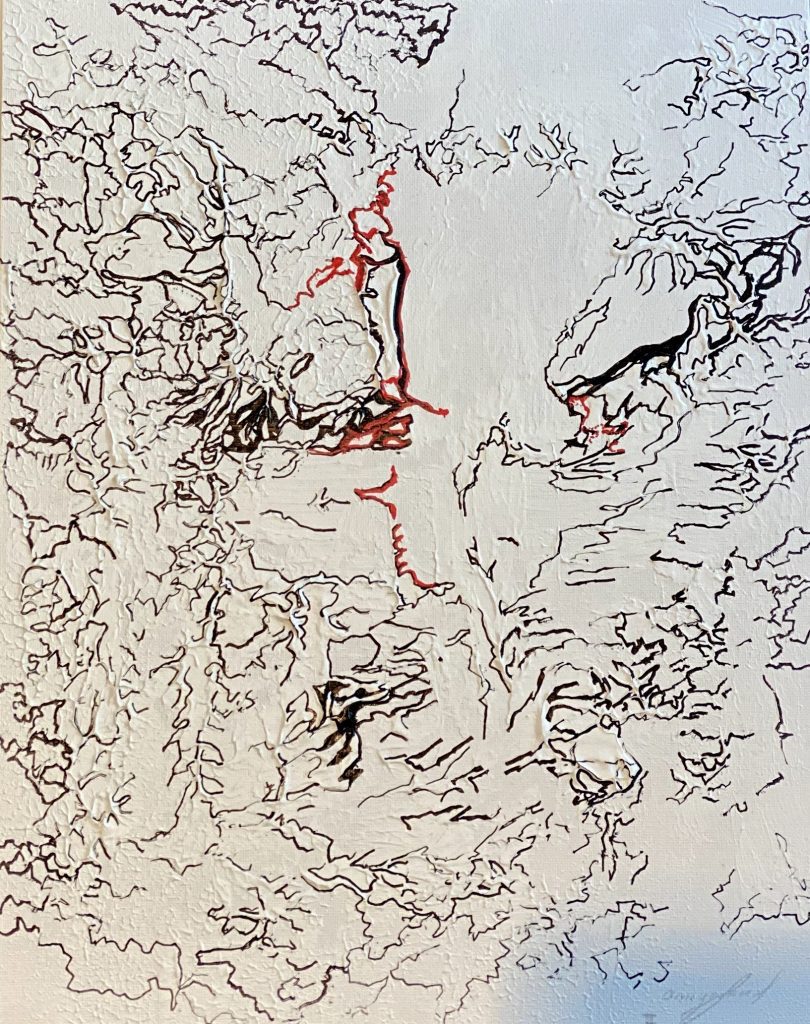

Week Two – Annya Sand

Week Three- Annya Sand

One could misread Sand’s statement as sounding like she’s toning her work down to appeal to the sniffy clique of art institutions, when perhaps what she’s really saying is that her brash early works were simply not connecting in a favourable way. As though she realised that the human facts that inspired her were already known — the hanging question being ‘am I an artist or a journalist?’

“My work used to be very informative and almost obvious in its political and social views. However, with time, I started to use a lot of hidden symbolism, especially when it comes to my choice of colour. In this way, I challenge my viewer to bring out their subconscious relationship with the power of colour and to use it in their discussions with my artwork and with themselves. I became interested in the symbolism of certain colours in religious art of the Renaissance, especially the contrast between black and white, and red and blue. I try to reflect this in my own work.

“Every single work of mine is a process of meditative art where I hold the conversation with that one canvas at that specific moment. I add new futures onto the canvas, and I wait for what the canvas is going to show me in return. I can only describe it as some kind of visual dialogue with myself and the canvas which can get very intense at times and almost obsessive.”

We asked Sand to describe how she works, how her paintings are planned to express and connect, and what her great challenges were:

I fear of talking about it! Talking about my artwork means talking about my deepest demons, and revealing a lot about myself. It can be hard to do this sometimes.

[Thinking about being collected by institutional bodies and organisations] I have never tried to analyse it. To be honest, I am a big fan of UNESCO and always have been. They invited me to take part in this sort of art residency, and since then I’ve been very much involved with them and what they stand for. I think the reason why they invited me is because I always have certain views on politics in the world and what’s happening around us. So I think that’s where we connected and continued our dialogue, but in the most creative way.

Given your political views, wouldn’t realism be a better fit?

I used to be more sort of a realist. My work used to be a lot more obvious, I’d say. Yeah. This work (brick graffiti) ‘we’re waiting for changes’. And that’s a quote from a very famous rock band in Russia during the 90s when it was a crazy Wild West time in all the ex-USSR countries. So this is very obvious but later work is less so.

Do you use symbolism?

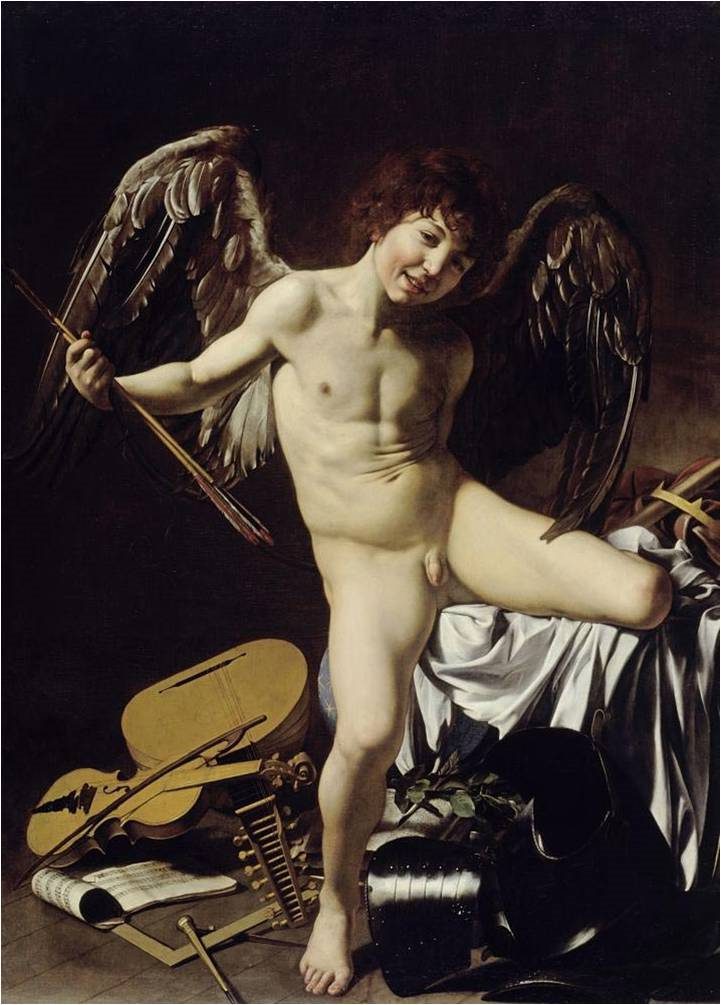

Yes, totally. I use a lot of colour symbolism, because back in the Renaissance time, that’s what they did. They used a lot of symbolism and you ask also about my painting. I mean you start studying the work and you almost get shocked from that power and the language that is in there and the information that is within that piece of artwork.

Amor Vincit Omnia by Caravaggio (1602)

The Mask 2009

In this particular work (The Mask, 2009), you can see a lot of brown and black which is more of a dark world in the Renaissance symbolism. But then you can see the contrast with white, for example. And yes, it shows demons within you. It shows also the struggle of trying to remove those demons. But also in my later work, I use a lot of grey and the contrast with the grey and yellow for example, or black and white. So it’s almost like that constant struggle and battle within ourselves that takes the main stage in my artwork.

Are you using Renaissance colour palette and structure?

Probably subconsciously. I tried to show it now as we are discussing it. I discovered that it’s very earthy. You see, probably if you asked me 10 years ago, I wouldn’t have said that.

I come from a very sort of classical school of art. My father used to be an artist. My granddad was an architect. So if we’re talking, and I used to paint and draw a lot of architecture, it’s almost automatic that you divide the canvas in your head. When I paint a portrait or architectural painting geometry is the main part of that work, because without it, you can’t really structure it. However, with abstract work I guess it’s quite automatic as I let it continue more freely. I’m part of it but I’m not so strict; quite the opposite actually. But then later when the work is almost finished, I have to look at it from the outside and try to make sure that the composition is geometrically correct.

How do you want people to decode your abstract works?

I think it’s up for interpretation. Art is very personal. You either like it or you don’t, you either want to have a conversation with it or you don’t. You either want to discover more about it, or it’s not your thing. So I don’t plan for that to happen. For example, if you come and you look at my work, or you turn away and you walk to another painting, it’s fine. If you start seeing your own things, and usually people do, they see their own story. So no matter how much I try to express my views and my sort of outlook into this world or my set or my world, the viewer always tends to personalise it to their own stories, so I don’t plan for a certain strategy when you see my work. There’s not a processional narrative in that way.

Of course, if I’m asked then I will talk about it. But equally if I am not asked I might actually ask the viewer what they see.

https://annyasandart.com/

@annyasand

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle