[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he car jostled over footpaths and pushed through the encroaching greenery, emerging into a clearing dominated by neem trees, a water pump, and a long, multi-room school.

The few women around the pump eyed us warily. Children hid behind their mothers. There were no men to be seen.

Our team leader, Rocky, explained, “You see, these men have fled into the bush, but they are close. Even the others, we asked, ‘how do you protect the women?’ and they said that they are just near.” Sure enough, a short distance on we met five men armed with Kalashnikovs. A small radio pumped music out of tinny speakers. These were the Thiiyic Galweng, the heavily-armed cattle keepers who keep watch over their community’s herds.

They watch not for lions or hyenas, though those beasts are sometimes found here in South Sudan, but for other men who come raiding for the cows that in Dinka and Nuer culture denote wealth, prestige, and power.

Now, however, these men were on heightened alert. One of their Thiiyic (pronounced Teach) kinsmen had killed the paramount chief from the Gony (Goyng) side and gone on the run. The Gony had responded in kind, storming through Thiiyic territory on a campaign of rape and retributive violence that they vowed would last until the murderer was apprehended.

The police officer who traveled with us exited the vehicle cautiously and spoke with the youth, who led us several hundred meters down a path and to another clearing encircled by several dozen additional heavily-armed men. They were here in hiding, they said. They wanted peace, and they knew that if they showed themselves it would lead only to more violence.

Nonviolent Peaceforce has been conducting peacebuilding activities in and around Lakes State for the majority of its existence in South Sudan. This is despite the fact that the state is overwhelmingly Dinka and does not, therefore, fit neatly into the international narrative of an ongoing ethnic civil war between the Dinka and Nuer. If everyone is Dinka, what is there to fight over?

Quite a bit, it seems, as the state is one of the most volatile in the entire country. The Dinka in Lakes belong to clans – the Gak, Agaar, Atuot, Ciec, and Aliab. Within this clan structure are sub-clans, and a multitude of conflicts have arisen over the years, typically related to cattle, grazing land, and women.

In Lakes, still waters run deep. Conflicts can last for years without any violence and suddenly flare up without warning. This latest, between the Thiyiic and the Gony sub-clans of Dinka Agaar, is a perfect example.

In 1997, Thiiyic youth murdered the son of the Gony Paramount Chief. Five years later, in 2002, the Gony struck back and killed the Deputy Paramount Chief of Thiiyic side. A Gony soldier, who is now a high-ranking government official, killed two of his own family in order to appease the Thiiyic, prevent retribution, and end the conflict. However, in early August of this year, seventeen years after the initial killing, the son of the murdered Thiiyic elder, who was only a child at the time of his father’s death, took his revenge by murdering the Gony Paramount Chief and fleeing into the bush.

The heavily-armed men we met deep in the bush were Thiiyic. They were angry and afraid. They had fled to avoid collective retribution, but the Gony had targeted their women, something unprecedented in the inter-clan conflict. Women and children had always been considered off-limits.

Perhaps in the context of the civil war, where an unknown number of women have been raped and where children are regularly abducted and pressed into military service, the rules of war are changing. What was once unthinkable becomes common. The rules have been broken, and one fears they may not be repaired.

In this context as well, when tensions are high, anything can be considered a further affront, and there is no such thing as an individual crime. A woman killed her nine-month pregnant neighbor in a dispute over a goat. Both were Gony, but the dead woman was married to a Thiiyic. In Dinka culture, dominated by patriarchy, a woman upon marriage loses her identity and takes that of her husband. In addition, the crimes of one person can often easily become those of the entire community.

Luckily, in this case, the Thiiyic weren’t seeing it that way. In the team’s meeting with the Thiiyic elders, under a tree in a clearing surrounded by armed men, they recognized the woman’s murder as an individual crime, one that needed to be resolved by the courts. They wanted peace, a chance to return to their homes.

Turning these issues over to the courts is an important extension of trust towards national institutions, and a big step towards reconciliation. That’s what we strive for – local solutions to local problems.

It is unclear whether the Thiiyic feel wholly comfortable petitioning their local government. Without going too much into the intricacies of South Sudanese politics, several high-ranking state officials in Lakes belong to the Gony sub-clan. These officials were already under pressure for the continuing intra-ethnic conflict in the state, and now that the violence is hitting closer to home, they’re under increasing pressure from state and national actors. It is just another reminder of how easily a local grievance can transform into a national issue, and how important it is when two sides can solve their problems peacefully and amicably.

The Thiiyic and Gony are not there yet, but the NP team in Rumbek is used to hard, arduous roads. As we left the clearing and the armed men behind, the team felt that we had made an important first step in reconciliation. The next day, the alleged murderer was turned over to the police.

It is only one step in along a long road to peace, but even the longest journey begins with a single step.

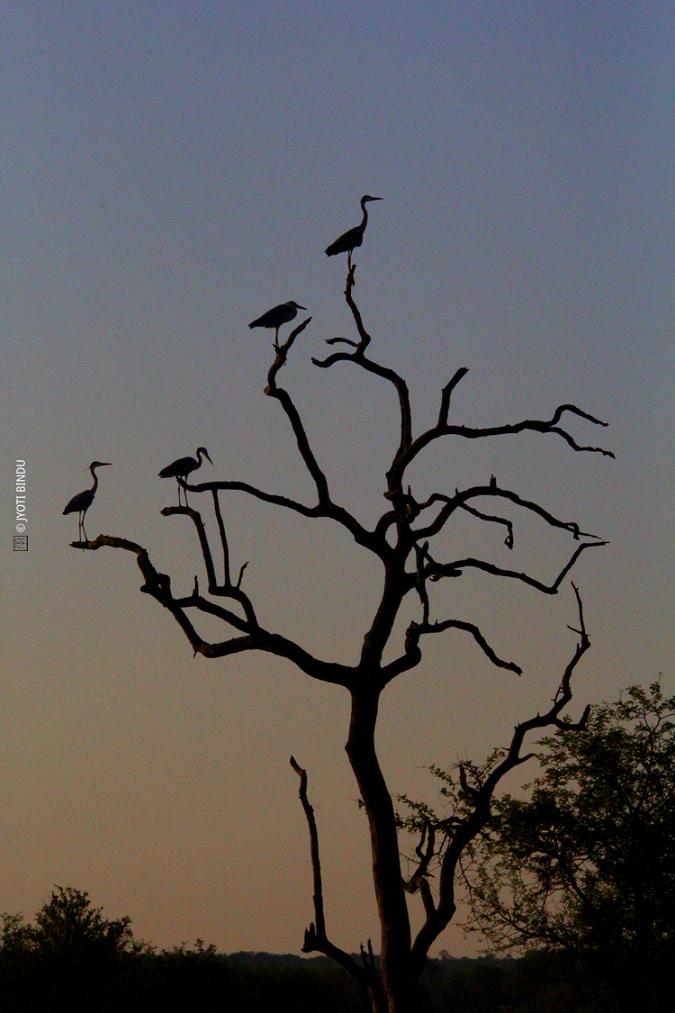

Image: Jyoti Bindu

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.