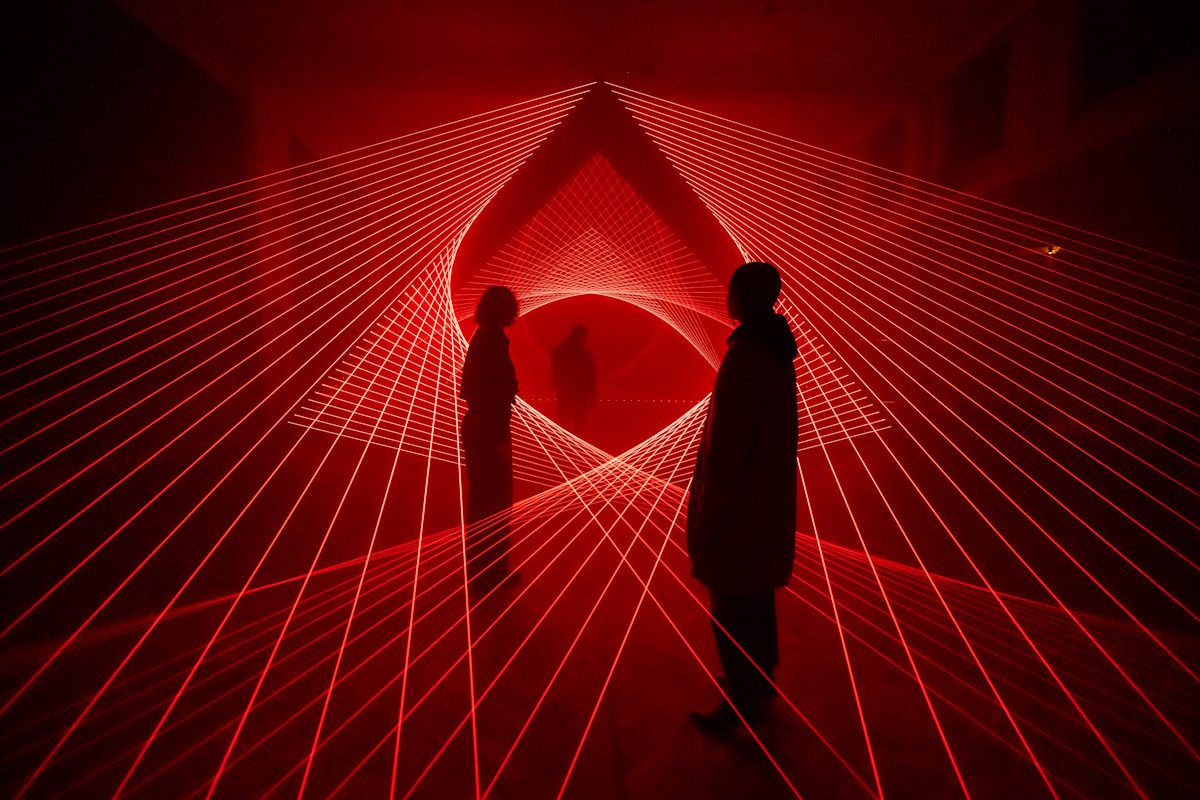

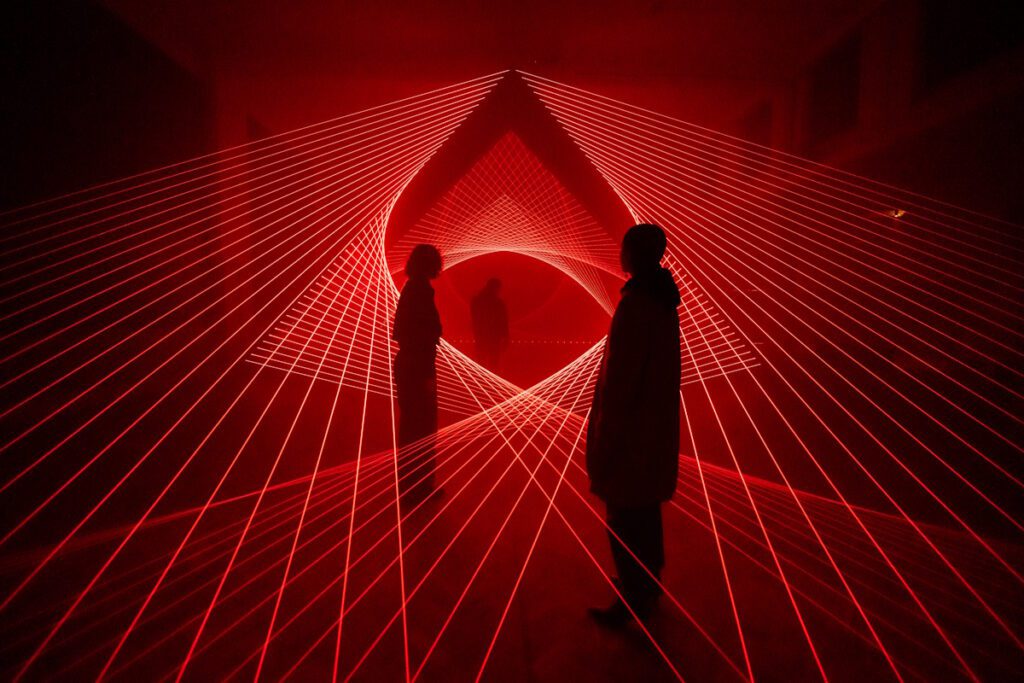

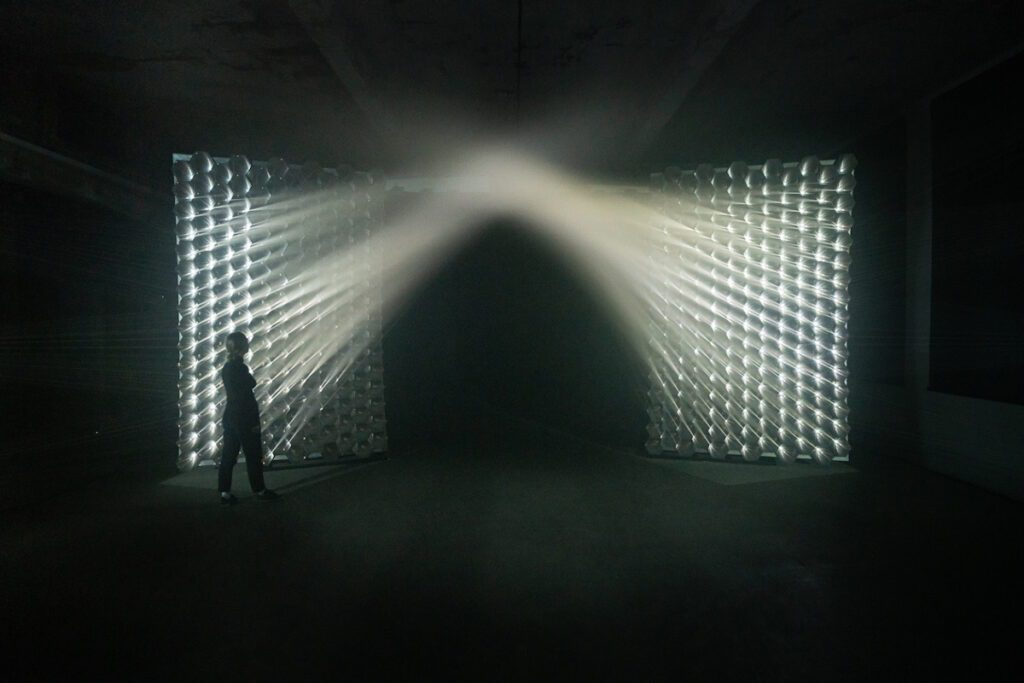

On March 16th, 2023, as curator, I guided journalists (and influencers) through the vast halls of The Beams, an old East London industrial building converted into an exhibition space. We viewed seven art installations in an exhibition called Thin Air. Large-scale and monumental in some cases, the site-specific works were all ‘New Media’ pieces, from a field of art that uses technology, light, sound, and architecture as its media.

On this tour, one journalist stayed apart from the group, frenetically taking notes. He stuck out to me as he was one of the few guests who didn’t seem particularly curious about the show. A few hours later, his article appeared online, giving the show a dismal review, essentially qualifying it as blinking lights, all fodder for influencers and selfie-hungry Londoners. From his perspective, it was just vacuous entertainment, lacking concept or meaning, pure spectacle with no substance.

I wasn’t surprised. In a lot of cases, boisterous technology-driven art is designed to impress rather than stimulate any kind of insight or emotional response. The creators seem keen to show that they are using the latest and greatest tech rather than ‘saying’ anything (or, in the worst cases, they are proselytising for the technologies).

This line of thinking is common, making one ask, ‘Isn’t it all just spectacle’? Maybe it is. But what’s wrong with that? How did it become such a taboo pursuit? Why does art that engages with technology fall so often into this facile reduction? Could it have something to do with our relationship to technology itself?

During the show’s three-month run, I interviewed all the participating artists. One, Matthew Schreiber, produces artworks that are, beyond their sheer beauty, designed to act as gateways into the question of art’s relationship to technology. He put it thus:

“It’s so, so critical to talk about it, and not shy away from the fact that anything using art and technology is going to engage in spectacle, and that it’s one after another; one trick, one gimmick, one novelty after another. If you don’t start discussing it and be aware of it, then what the hell is it? If you stripped all of this kind of work of its novelty, what would be left? So that’s a problem to solve.”

What does it mean to ‘engage in spectacle’? If we rewind to the origin of the negative connotations around the notion, we’d find Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967), a seminal book that exposed the ways our societies were slowly being sucked into a mediated reality. In his first paragraph, Debord writes:

“In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.”

For Debord, spectacle commodifies art, encourages passive consumption, and creates a ‘false consciousness’, where our representation of the world is mediated via entertainment rather than lived first-hand, becoming a form of social control.

Expanding upon Debord’s concepts and aligning the term ‘spectacle’ with Schreiber’s interpretation, its meaning is closer to entertainment than to art. In this context, it embodies an experience devoid of critical engagement—something enjoyed for its immediate, pleasurable impact, a fleeting and impressive ‘wow’ moment that swiftly fades or gives way to the next Instagram-worthy distraction.

One could argue that there is a ton of art production out there that is akin to spectacle. So why should ‘good’ art stand in opposition to it? To answer this, we need a working definition of ‘good’ art. My current favourite was proposed by Nicolas Bourriaud in his book Inclusions (my translation from French is below). He states that an artwork can only be defined as a ‘relational regime, a specific level of understanding of the world, used by humans in sometimes mysterious ways.’ He continues,

[an artwork must] ‘combine formal mastery, visual and intellectual complexity, the capacity for the artist to encode information and sensations in matter (or in time) and to bring forth the mental challenges of the period they are in’.

From that perspective, spectacle does seem like a downgrade from art. It is like consumerism, a short pleasure, soon forgotten for the next dopamine hit. And this is why installations that use the same materials and technologies as New Media artists often fall into the trap of producing spectacle for the sake of entertainment: they rely on the creation of short-term awe, a cheap magic trick that plays on the audience’s desire to understand ‘how it was done’. On the other hand, those who tend to condemn, blanket-fashion, all types of art that use technology tend to be, if not Luddites, sceptics with a resigned attitude towards technology in general.

This is why the question of our relationship with technology is so important to unpack.

Bernard Stiegler, a French philosopher who was extremely prolific on this topic, explores the history of our connection with the technical in a series of books and essays. He establishes a few key moments.

The first is Plato, who starkly opposed two forms of knowledge: Episteme and Tekne. Episteme is the quest for real knowledge, for truth, whereas Tekne is something akin to “technologies of knowledge”— rhetoric, tricks and smoke screens. Plato developed this concept around his hatred for Sophists. Sophists believed that rational thinking could be used to serve whichever purpose one deemed necessary. They developed rhetorical and oratorical skills that led to a relativistic philosophy that challenged the notion of truth as a unique and absolute value. They trained themselves to argue any perspective and its contrary. For Plato, this was a form of ‘technology’ because it was a form of rationality that was purely utilitarian, a means to an end.

George Simondon, a predecessor of Stiegler, who wrote extensively about technology, points out that the tension was set between culture, which is teleological (ends-driven), and ‘technics’, which are utilitarian.

The second milestone, according to Stiegler, is the post-Marxist response to industrialization. If technology (in the context of industry) is a method of control over workers, it becomes an alienating force. And if industry becomes global, it entails a slow destruction of local cultures as it forces down our throats a single method of doing things, an ‘instrumentalization’ of all means of production, to use Marxist lingo.

In his 1965 article ‘Culture et technique’, Gilbert Simondon turns this issue on its head. He reminds us that the word ‘culture’ derives from techniques of ‘cultivation’. Thus, culture is a product of utilitarian ‘technics’. Somehow, culture was elevated above these lowly origins and looks down on them with disdain:

‘Now, when the word culture is used today to speak of man as a cultured or cultivated being, despite the word’s technical origins, a disjunction, maybe even an opposition, is set up between the values of culture and the schemas of technicity: man as technician is not the same as man as a cultivated being. Culture is a disinterested repository of values, while technics [la technique] is an organisation of otherwise indifferent means towards ulterior ends; culture becomes a kingdom of ends, while technics tends to be a kingdom of means that must sustain a being under the authority of the kingdom of ends; culture has domesticated technics like an enslaved species [espèce asservie]’.

For both Simondon and Stiegler, technics need to be understood as essential to our humanity. Stiegler likes to bring up the legend of Epimetheus. Epimetheus was Prometheus’s brother. When Zeus asked Prometheus to distribute positive attributes to the creatures he had formed, Prometheus agreed to allow his brother to do it. Unfortunately, Epimetheus distributed all the traits but forgot to give any to the humans. Prometheus decided he needed to steal fire from the gods to give humans some form of strength. For Stiegler, this means that humanity’s gift is its ability to use external resources to thrive. Humans are humans because they have prosthetics, appendages that allow them to control their environment and survive. Technology is not an add-on to our humanity, it is part of our nature.

To bring all this back to art and culture, if we can see that technology is essential to our ‘humanness’, we have to then accept that understanding technology is a key part of our self-understanding. Cultural producers, artists, critics, and curators shouldn’t denigrate it based on the flawed Platonic concept of technology as a ‘tool’. If we are served art and technology as spectacle, we miss the opportunity to see technology as a means to develop our individuation.

Without going too deeply into the difficult concept of individuation, we can say it is a critical component of a healthy society. Stiegler was vehement in his critique of what he called a ‘synchronisation of consciousness’, which could be defined as the way humanity starts thinking in a single track, fed by globalised media and culture industries. This is where spectacle as entertainment becomes problematic, almost a form of hypnosis, lulling spectators into a vacuous ‘mainstream’ where everyone thinks and ‘likes’ alike. Healthy individuals have their own desires, their own ability to extract meaning from their environment.

If we all want and are served the same thing en masse, then what drives us as individuals to engage with the world (aside from the necessity of satisfying our basic needs)? According to Stiegler, spectacle leads to a loss of societal ‘libido’ or desire. If we are told by marketing departments that what we should want are ‘immersive art shows’ but these only provide us with short-term gratification (and a few Instagram posts), we are not creating any new libidinal drives, curiosity, or any real desire. And this is where the camp of technology sceptics has a point.

Why must art and technology shows be marketed as dopamine hits rather than ‘thought-provoking’ or ‘conceptually challenging’? According to Simondon, this is because our society creates cognitive schemes that favour forms of culture that see technology as a tool, a tekne. When we grow up and have to start interacting with technology more deeply, the damage has been done and we cannot see in it the light it shines on our being. For Simondon, the educational process should be reversed. We should start education with a deep dive into technology and bring ethics, religion, and culture in the later years. This would allow us to understand technology as what it is, a pharmakon, both poison and remedy, not either/or.

Exhibitions of the scale and ambition of Thin Air are extremely costly to develop and mostly operate outside of state funding. They rely heavily on marketing strategies to attract a big enough audience, as ticket sales are the main source of financial revenue. Given this responsibility, marketing teams have to find the appropriate language to speak to a wide swath of the population, and thus often need to use expressions such as ‘immersive ’ and ‘mind-blowing’. Artists might not want their works to be described in that language but know that it is the game they have to agree to play. If their work happens to be a commentary on spectacle, as is the case with Matthew Schreiber and others, how does one balance on a tightrope between spectacle and ‘meta’ spectacle? Maybe one answer is Larvatus prodeo, as Descartes famously said (‘I go forward masked’). Spectacle as a mask for a larger discourse around technology, in a time when this discourse is needed more than ever, is maybe the way New Media Art exhibitions have to operate. Finding a place between tech evangelism and a widespread suspicion towards the transformative power of technology is a difficult task, but one Thin Air was designed to embrace.

Images courtesy of Broadwick Live

REFERENCES

Bourriaud, Nicolas (2021). Inclusions: Esthétique du capitalocène. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. Translated into English by D. Beaulieu as Inclusions: Aesthetics of the Capitalocene (2023). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press/Sternberg Press.

Debord, Guy. (1967). La Société du Spectacle. Paris: Editions Buchet-Chastel. Unauthorised translation into English as Society of the Spectacle (1967). Madison, Wisconsin: Radical America; and Detroit, Michigan: Black and Red.

Simondon, George (1965). ‘Culture et technique’. Brussels: Bulletin de l’Institut de philosophie, vols. 55–6, nos. 3–4. Translated into English by O. L. Fraser and revised by G. Menegalle for Radical Philosophy, vol. 189 (2015), pp. 17-23.

Sinha, Vamika. (2022). ‘Sensory Technology’. Aesthetica Magazine, issue 113 (June/July). Available at: https://aestheticamagazine.com/sensory-technology/

Stiegler, Bernard. (1994). La technique et le temps: La Faute d’Épiméthée. Paris: Éditions Galilée. Translated into English by Richard Beardsworth and George Collins (1998). Technics and Time: The Fault of Epimetheus. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Alex Czetwertynski is an artist and curator. His practice includes large-scale media installations, film and animation. His work has been shown at the Met and the FIAF in New York, the Centre Georges Pompidou, and the Théâtre de la Cité in Paris, the Confort Moderne in Poitiers, Museum of Literature in Warsaw, the Museum Ludwig in Budapest, and more.